Fossil tree roots in the Catskills feb. 20, 2020

Fossil tree roots in the Catskills

The Catskill Geologists

Robert and Johnna Titus

The Mountain Eagle, Aug 5, 2017

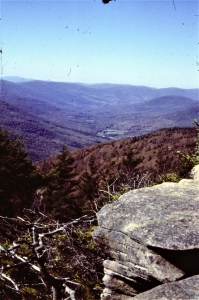

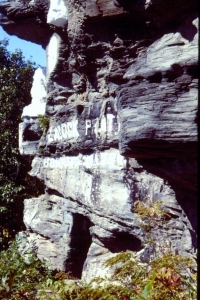

If you are accustomed to reading our columns then you might like to get out and do some geology on your own. Let’s give you a good project to work on. We are hoping that you might make some discoveries that might help us. We would like you to take a look at our photo. It’s a horizon of reddish Catskill sandstone. It’s a stratified sandstone and, especially at the top, you can see strata that range from a half inch to a full inch in thickness.

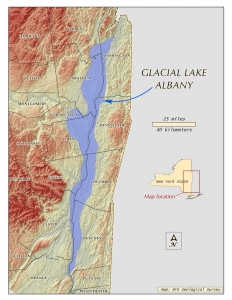

That red color, here in the Catskills, tips us off as to what kind of environment these strata formed in. Red is the color of terrestrial deposits. These strata formed on dry land. This was on the floodplains of the Catskill Delta and we have written about it before in this column.

But what is special about these strata are the petrified root systems that were preserved within them. You can see one root system on the far left, another just a little left of center and the third to the right. What a remarkable thing this is; we are looking at the fossilized root systems of three plants that, long ago, grew on the surface of the Catskill Delta. All of the foliage that once rose above the ground is now gone but there are the roots.

These plants were part of what is called the Gilboa forest. That’s the oldest known fossil forest known to science, so these are important. They date back to the Devonian time period and are probably about 380 million years old. Potentially these fossils might tell us something about what early forests were like.

Paleontologists sometimes call these fossils “rhizomorphs.” That roughly translates as “root morphologies” – structures that preserve the forms of ancient plant roots. What kinds of plants were these? Well, that is the important question – we really don’t know. Given the modest size of these root systems we expect that they would be called shrubs, but what kinds of shrubs were they? Again – we do not know.

Shrubs of this sort can be considered to be small trees. Most of the trees that are known to have grown in in the Gilboa forest have well known and easily identifiable root systems. They don’t look like these ones. So – you can see why we are interested in them. These may be something new.

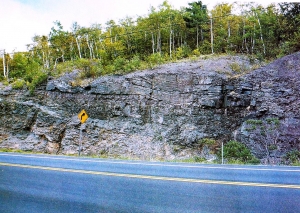

We found these fossils along the dirt road that ascends Mt. Utsayantha in Stamford. We parked our car at the bottom of the hill and walked to its top. We hoped we might find something of interest in one the many outcrops that we found along the way. It’s easier to drive to the top, but you are more likely to find something interesting if you walk. These specimens were in an outcrop that lay about halfway to the top of the mountain.

Well, here is the main point of all this. It seems likely that there may be many more specimens like these scattered perhaps throughout the Catskills. There are only two of us, but there are many more of you. Once you have seen our photo you will have a good idea of what to look for. Once you know what to look for it’s easier to find things. Maybe you can tell us where some more of these are.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page The Catskill Geologist. Read their blog thecatskillgeologist.com

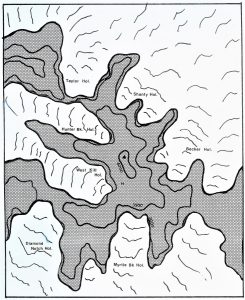

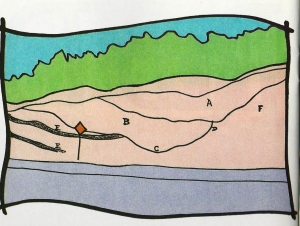

T – Taconics; B – Berkshires

T – Taconics; B – Berkshires