The Devonian of Greene County, Part Eight

Rising out of the Sea

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

On our journeys back to the Devonian time period we have been visiting a very different Greene County. It was, back then, a tropical land; surprisingly our landscape lay about 20 degrees latitude south of the Equator. That’s about as far from the equator as Cuba is, and it’s quite warm at such latitudes. We have seen the evidence for the tropical climate – right here! Our county has a great amount of limestone that dates back to the Devonian and limestone is the product of shallow tropical seas (it’s what the Bahamas are made out of). But we also see evidence of times when very deep waters covered Greene County, that evidence was in the black shales that are also common around here. None of this is surprising, it is, of course, a geological history and through long spans of time things gradually change.

Today’s episode takes us into a time of transition, and you can go and see some that change for yourself. What we have not seen much of on our journeys is sandstone. Sandstone is one of the most common rocks that a geologist is likely to encounter, but, around here, very little of it formed during the early stages of the Devonian. That would all change.

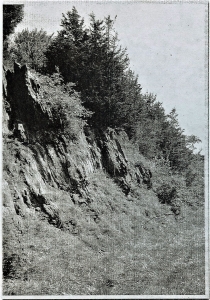

Go to Rte. 81, east of Greenville, and find your way about 8/10ths of a mile west of the Quarry Restaurant. There, along both sides of the highway, is a fine set of outcroppings. We found the north side offered the best views. Before we get started, we would like you to take a good look at the whole outcrop. You will see a series of closely spaced and nearly parallel fractures. They are very steep but are also inclined just a bit to the east. They give the image of stratification but that is deceiving. Geologists have to be careful not to be fooled by rocks and that is easier that you might think. The actual stratification is inclined gently to the west, but it is quite difficult to perceive. The fractures that we have been looking at are called rock cleavage. With such cleavage the rock breaks into numerous closely spaced and parallel fractures. Because cleavage planes have the appearance of stratification, they serve to hide the real thing.

Now, let’s forget about the fracturing and take a good look at the rocks themselves; they are what is important here. Look towards the downhill, east side of the outcrop. You will observe that, down there, the rocks are dark and very fine-grained. These rocks are pretty much the same black shales that we saw last time. They represent a deep-water marine environment. But, turn around and look uphill a bit and you will see that most of the outcrop is lighter in color. Get up close and you will find that this lighter colored stuff is composed of sand grains; this is sandstone.

Everybody remembers the story of Columbus crossing the Atlantic. After two months of westward sailing his crew was getting very anxious about when they would find land. They wondered if there even was land out there, was their journey a dangerous and futile effort? Well, the appearance of floating twigs of land plants reassured everyone; there was land ahead. Soon they found it.

Our discovery of sandstone plays much the same role as those twigs. We have been “sailing” across a Devonian sea and, so far, there has seemed to be no prospect of finding land. Those dark shales, at the bottom of our outcrop, belong to the open ocean. They are the last beds of the Marcellus Shale. But the rest of the outcrop tells a different story. This sandstone belongs to a new geological formation, which is the Mt. Marion Formation.

The Mt. Marion Formation was deposited at the bottom of a sea, the Catskill Sea, but it is a nearshore version of that ocean. Columbus’ twigs were found near to the shore and so too are large quantifies of sand. Grains of sand don’t weigh very much but marine currents have a hard time carrying them offshore, so sands accumulate near the coast. That’s the case here.

The Mt. Marion is a marine deposit and we relished the prospect of finding fossils at this outcrop, but we were mostly disappointed. In other places the Mt. Marion is rich in the remains of Devonian shellfish, but not in Coxsackie. We did a little fossil hunting, but we found nothing much, maybe you will have better luck. We did find something of interest; it was a fossil, but not the fossil of a shell. We found the fossilized burrows of worms. Back when this was marine sand, the Mt. Marion had marine worms living within it. Like today’s earthworms, these humble creatures consumed sediment and found nutrition within it. They left behind the evidence: the sands still retain the patterns of their burrowing. Look about ten feet below the top of the west end of the outcrop. We left a small white paint rectangle to mark it.

This sandstone is named after, of course, Mt. Marion, down in Saugerties. Maybe you have driven south along the Thruway and seen Mt. Marion. It towers above the western horizon. The mountain is so big and so steep because of its sandstone composition. Down there the Mt. Marion Formation is composed of fairly pure quartz sand. Quartz is very resistant stuff and it holds up well in the face of weathering and erosion. That’s why Mt. Marion is such a prominent feature in Saugerties.

But what about up here? It would seem that here the Mt. Marion is not quite so pure, there is a fair amount of silt and clay in it. Up here the rocks are a little less resistant to weathering. We do have a “mountain” up here, and you will probably know its name: Potic Mountain. But this mountain just barely deserves such a designation. If you drive east from Coxsackie to Greenville, you will be crossing Potic Mountain, but it just won’t feel very mountainous. Still, if you follow it on a map, Potic Mountain traces south right into Mt. Marion, only the composition of the sandstone has changed.

What the Mt. Marion lacks in altitude it makes up for in thickness; it’s about 1000 feet thick in our region. That’s a lot of sandstone and it was once a lot of sand. Where did it all come from? We answered that question in the last episode. Off to the east, there was a rising range of mountains: the Acadians. At that time, they must have already reached elevations of thousands of feet. Today all that is left of them are the hills of the Berkshires. What happened to the rest? Well, a lot of it was weathered into sand and much of that sand was deposited here in eastern New York. Our one thousand feet of sandstone was probably once several thousand feet of mountain range.

In the end, we have visited a humble outcropping of rock. Most of you have probably passed it numerous times without giving it a glance. But now you know better. This outcrop records the moment in time when the great Acadian Mountains of western New England were beginning a rapid and very impressive uplift. In terms of Greene County, this humble little outcrop represents a lot of history.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”