The Devonian of Greene County, Part Six

End of an Era

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

New Baltimore’s Limekiln Road runs south to north in the very pretty northeast corner of Greene County. It’s steeped in history and, as we are sure you can guess, much of that history is centered around a lime kiln. To drive there head east from Greenville on Rte. 26. Go 9.7 miles east from Stewarts, turn left onto Limekiln Road and continue north. You will go exactly one and three quarters miles north to get to your destination, but don’t be in a hurry. A little more than a mile along the way you will see the lime kiln itself on the left side of the road. A historic marker states that the kiln goes back to the 1850’s, but it’s still in a very good state of repair. It must have been quite the operation back then because there has been a lot of quarrying along the road. Watch carefully and you will see remains of the excavations that once fed limestone into the kiln. The rock ended up as lime and fertilizer.

As we said, there is a lot of history here. But we will find that this 19th Century history has allowed us to see into a much deeper period of the past. Continue north another half mile along the road and you will soon see pools of water just to the right (east) side of the road. Here more of the old quarrying carved out a rough basin. Quarries always provide geologists with keyholes into the distant past; this is a very good keyhole.

In the five earlier episodes of this series we have traveled through a great deal of the Devonian time period as it is recorded in Greene County geology. It is estimated that the Devonian began about 419 million years ago and, in our last installment, we reached a time of perhaps 396 million years ago; we have so far traveled through about 20 million years or so: not bad.

We have witnessed the comings and goings of several very different types of oceans. First, we saw a limestone producing Helderberg Sea, something that might remind you of the Bahamas of today. Then we saw the black shales of an enormously deep ocean, the sort of place where you would look for a sunken ocean liner.

In this episode we start a new episode of our area’s history, when there was the return of another shallow tropical sea, once again something very much like the Bahamas of today. We are going to visit some very nice limestones. These are called the Onondaga Limestone and, once again, we will find that they have quite a story to tell.

Limestone was the focus of the first four chapters of this saga. We remind you that they are the sorts of rock that originate in shallow tropical seas. Visit the western coast of Florida, famed for its shell collecting, and you will see just exactly this sort of habitat. Fossil rich limestones are forming there today. Travel to the southern tip of Florida and go snorkeling, and you just might be fortunate enough to be able to explore a coral reef. Someday, some of these reefs will harden into limestone and become fossil coral reefs.

As you will probably guess we don’t have to go to Florida, or the Bahamas, to see such wonders; our trip to Limekiln Road has brought us to a very good one. Above us is an inconspicuous hill named Roberts Hill. It’s a pretty little place, but not the sort of landscape that would attract much notice. But look above you and through the woods, you will see a number of outcroppings of limestone. A closer look will tell you something most remarkable: this hill, all of it, is a fossil coral reef. See for yourself. At first you only see inconspicuous gray outcrops, but close up it is all very different. The rock is “alive” with corals. You have to see this to believe it, but it is there. The reef even has a name; it’s called the Robert’s Hill Reef.

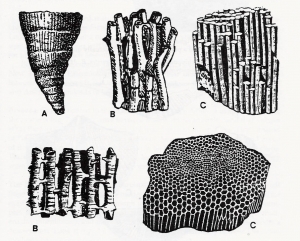

Stand along the side of the road and gaze up at Roberts Hill. Now your mind’s eye must travel back in time. It is the Devonian and all around you are the agitated waters of the tropical Onondaga Sea. Rising in front of us is the murky image of a great coral reef. Immediately in front of us are a number of coral mounds. Rising above these are the skinny arms of branched corals (B on picture); these colorful arms seem to reach out towards the water’s surface. Farther up, near the top of the reef we see a large cluster of smaller and shorter corals. Each of these has the shape of a cow’s horn (A).

Look straight up and you will see the undersides of passing waves. They sparkle in the sun as the swells and troughs pass overhead. The waves are approaching the reef from behind us (the southwest). Our eyes can follow any one of these waves and watch as it closes in on, and then smashes into, the reef in front of us. The collision stirs up a chaos of bubbles and silt. Together, these materials make our view of the reef an indistinct and cloudy one. Below and behind us is a rubble of broken dead corals. This litter records damaging episodes of intense wave activity. Roberts Reef can be a very rough place to live.

Today, the waves are quite strong, and few animals are venturing out. The corals are well adapted to the stress, but all the fish have hunkered down. They are hiding in reef crannies and they are out of sight. It’s too bad about that. Suddenly, an especially great wave crashes into the reef and our image of it is completely obscured. In a flash we are back in the present and the summer greenery replaces our view of the reef. It’s nice to look at but just not the same.

Our trip into the past was too brief, but let’s use what we learned to make the best of it. This outcrop is a hash of whole and broken corals, probably preserving most of the original reef. Take a look and see for yourself. We found the best fossil hunting in the roadside knob just south of that small pool of water. You won’t have to climb around very much; the nearby exposed rocks there show most of what you need to see.

There are three broad categories of corals to look for. The biggest are not the most common and not the easiest to find, but they are worth the effort. They are the old coral heads that grew into mound-like forms. Look for large dark corals, up to two or three feet across, and focus on the detail. You can identify these from the honeycomb patterns within them (C). Each honeycomb chamber was once inhabited by a single coral animal, so the coral head makes up a colonial structure, coral apartment houses. The second type of coral can be recognized by its circular shape. Watch for something that sort of looks like the cross section of a gray orange. The appearance is misleading as the whole specimen actually has a horn shape. It’s only the cross-sectional view that looks circular. These, logically enough, are called “horn corals (A). “They lived in clusters on the reef. The third type is a digitate coral. In this case a number of corals grew together in branches (digits) that reached up toward the currents (C). You will mostly cylindrical fragments of their branches, often with many of them lying parallel to each other.

If you have never seen anything like this before, we think you will find it to be most remarkable. Look all around you; today it is Greene County in high summer and all around the greenery is beautiful to see, the air fresh to breath. But we have already looked at all this with the eyes of geologists; all around us we have seen the relentless wave pounding of a sparkling shallow tropical sea. We have seen reef corals reaching out to these waves. We have found that this space, back in the Devonian, was a very, very different place indeed.

If you make your return trip down Limekiln Road watch for two more exposures of the Onondaga Limestone along the way; they are fine cliffs on the right (west) side of the road. Notice that with these outcrops there are no fossil corals. These strata expose a different environment of the Onondaga. These well-stratified limestones formed in the open ocean; a habitat without any reefs. It seems that the Onondaga Sea was too deep here to allow coral reefs to get established. The reefs are all found to the north; in the south the ocean was a different open ocean ecology.

All this represents an end of an era. After the Onondaga there would never again be a time of such shallow tropical seas in Greene County. Our county would never again resemble the Bahamas; a major period in its history was over.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page at “The Catskill Geologist.”