A Fossil Hurricane? Oct 10, 2024

“Hurricane Dorian” hits the Catskills?

The Catskill Geologists; The Mountain Eagle; Oct 4, 20

Robert and Johanna Titus

Like so many others, the two of us watched with awe, horror and fascination as Hurricane Dorian passed across the Bahamas (2019). We have spent time in the Bahamas, and we know what a low-lying landscape it is. There is so little to stand in the way of such storms. So, as geologists, we know exactly how devastating a powerful hurricane can be in a place like that. Winds of 120 miles per hour swept across lightweight homes, broke them into pieces and swept them away in large numbers. We expected to see that; we feared seeing that and we did see that.

The power of this storm was so great that you might guess that it could leave an imprint in the fossil record, and we are guessing that it did just that. Will Bahamian geologists of the very distant future find a record of Dorian? We think they will. But what about our Catskills geological past: does it present us with evidence of such storms? That’s something the two of us are always on the lookout for, and we would like to tell you about one example that we have found.

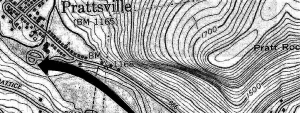

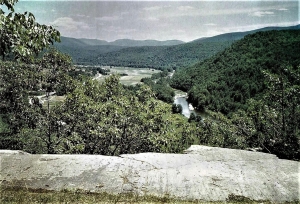

Let’s take you down to Rte. 9W in the Town of Glasco. That’s a little north of Kingston. There you will find a very nice road outcropping which displays something called the Glasco Limestone. The rocks there are stratified. Like almost all limestones, these strata represent the floor of an ancient and shallow tropical sea, much like the Bahamas of today. Each stratum represents a moment in geological time. Some are thicker than others; the thick ones sometimes record more exciting moments.

We found one that was very exciting indeed. Take a look at our photo. It shows a five-inch-thick stratum of the Glasco Limestone which is packed with coarse sediment and fossil shells. Notice how there are so many fossils down at the bottom of the stratum; they are relatively big ones too. Notice too, that as you look upwards, the fossils become fewer and smaller. That tells the story.

Back during the early Devonian time period, about 400 million years ago, this was the bottom of the shallow, tropical Glasco sea. It was approached by and overwhelmed by a powerful storm, perhaps a hurricane. In the space of hours, the currents picked up great masses of shells and sediment, and then carried them in the direction the storm was moving. Imagine a mass of watery sediment actually moving across the shallow sea floor. All storms end, and as this one passed, its currents slowed down. Coarse sediments and large shells dropped out of the flow first. They formed the bottom of our stratum. The storm continued to slow down and finer grained sediments with smaller shells settled out of the flow. When the storm was finally gone, it left behind the stratum that we found, coarse grained at the bottom, fine grained above. With time it hardened into what might be fairly called a petrified storm deposit. Geologists sometimes call them tempestites.

This was a truly devastating event, and many shellfish and seaweeds died because of it. But there were no creatures who understood what happened on that day and certainly none who would go on to even remember it. There never was any record or memory of this storm until hundreds of millions of years passed, when unusually bright primates came along and took a good look at these rocks.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist

Japanese knot weed

Japanese knot weed