A Maze of streams – Oct. 20, 2022

Into the Maze

On the Rocks – The Woodstock Times

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

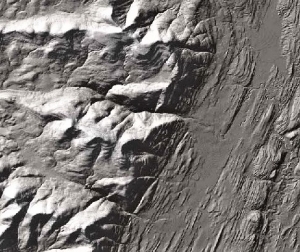

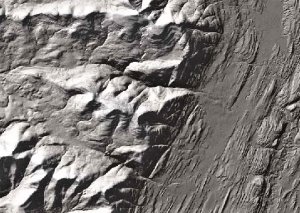

Look at a good, detailed map of the Hudson Valley in the vicinity just east of West Saugerties and Manorville. If you focus on the streams long enough, you just might notice something odd. A series of rivers descends the Catskill Front. Plattekill Creek is the most prominent, but there are several others, mostly unnamed. They all start out fine, descending picturesque mountain canyons as typical mountain streams. Then something peculiar happens. They all enter into a confusing complex maze of streams. Almost all the rivers and their tributary systems display a prominent north-south orientation. Within that pattern there are a large number of abrupt left and right turns as well. That gives our drainage a lattice-like appearance. We have searched the geological lexicon and we are not exactly sure what this should be called, but we think “rectangular drainage” is the best choice. It’s a curious pattern and, of course, there’s a reason for all this.

It all has a lot more to do with the bedrock than the rivers. You see, throughout much of this area there are alternating layers of sandstone and shale. All these stratified rocks are inclined; they dip into the earth toward the west. What that means is that the crust was once actually moved, tilting to produce north-south ridges of very solid rock.

The bedrock geology has been like this for probably hundreds of millions of years, but in recent times there have been changes. A mere 15,000 years ago, the Hudson Valley glacier flowed south through the valley. The ice must have been several thousand feet thick, and it acted like a great sheet of sandpaper. The passing glacier eroded the bedrock. Naturally the ice has had little trouble scooping out the shales, they are so soft. But the ice had much more trouble with the sandstones. Tough as that stuff is, the glacier was still able to pluck loose large blocks of it and carry them off. The ice actually adheres to the rock and yanks it loose. That has sharpened and straightened the many ridges of sandstone.

All this leads us back to those rectangular river patterns. You see rivers have a very hard time getting through the ridges of sandstone, so they have followed the shales. They have eroded out their channels along the bands of the softer rock. Still, a Hudson Valley creek eventually has to east toward the Hudson River. So, from time to time, the creeks have found breaks in the sandstones and have worked their way through those ridges. That’s the origin of the sharp rectangular turns.

Plattekill Creek is typical. It is a gorgeous mountain stream as it drops out of the Catskills and passes through the village of West Saugerties. Everything continues well until it reaches the vicinity of Blue Mountain and the Saugerties Reservoir. There it abruptly makes a sharp south turn and follows a beeline in that direction for three miles. Here it is nestled between ridges of sandstone.

It’s in this vicinity that Plattekill Creek has entered that maze of tributaries. And it’s here where that north-south lineation of the drainage is best developed. We have worked the area and we believe that there are about 11 ridges of sandstone here. All of them offer barriers that can confine the tributaries into those north-south straightjackets. You can see some of these ridges and several more. Head east on Rte. 212 until you get to Shultis corner and the intersection with the Glasco Pike. From here, you can head east and count the ridges of rock that cross the pike. Or you can continue on Rte. 212 and count the ridges on your way toward Centerville. If you do count the ridges, don’t expect the numbers to come out the same. We get different numbers every time we take the route. Geology isn’t Physics and we don’t worry too much about exact numbers.

Plattekill Creek eventually has to cut through to the Hudson and it begins the hard part of its journey near where it is crossed by Rte. 212. Between here and its junction with the Glasco Turnpike, the Plattekill has to cut its way through the tough rocks of the Mount Marion ridge. In some stretches of this flow, the Plattekill has been forced to carve real canyons. You can take the Fish Creek Road north from High Woods and cross the Plattekill in this vicinity.

In the end, there is nothing all that special or mysterious about this maze of rivers. It’s just another among many landscape features, but a geologist does take a quiet satisfaction from noticing and understanding.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”

Hoogebergs – lower right

Hoogebergs – lower right