Sam’s Point in the Shawangunk Mountains May 24, 2018

Visions of a Hudson Valley geological past: Glaciers at Sam’s Point

Watch out for moving ice

Robert and Johanna Titus

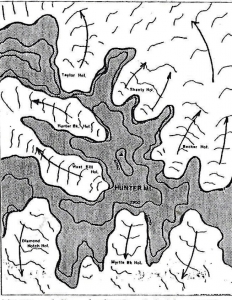

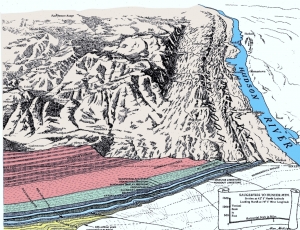

The Shawangunk Mountains are certainly among the most scenic locations in our region, and uniquely so. This ridge of resilient quartz sandstone towers above the Hudson Valley. One of its most popular locations is Sam’s Point Preserve, near the south end of the mountains. It’s thousands of acres are perched atop the mountains at elevations well above 2,000 feet. It’s owned by the Open Space Institute and managed by the Nature Conservancy. In the past there were commercial uses of this land. There were abundant blueberries here, and people were hired, every summer, to come and pick them. Then, in addition, there have been several resort hotels.

But we came here to learn about the geology. How had the area’s geological history given rise to this scenic wonder? We headed up the trail. It didn’t take long to figure out why the Shawangunks are even there. All along the trail were massive outcrops of quartz sandstone and conglomerate. Quartz is very resistant to weathering and a mountain made out of such rocks will stand out as all other bedrock around it erodes away.

We got up to Sam’s Point itself and soon learned much more about the geological history that went into creating the landscapes we see today. We arrived at the easternmost of two sandstone platforms, each seemingly designed for sight-seeing. Naturally, we were more interested in looking down at the rocks than gazing at the distant scenic views. There was some special things that caught our eyes.

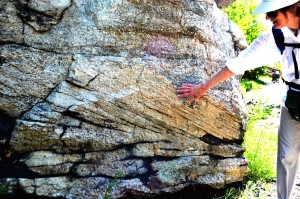

We saw a polished sheen and faint scratches on the surface of the rock. We quickly recognized these to be common ice age features. Sam’s Point has had a long ice age history, probably going back to the time when glaciers first came down the Hudson Valley. At that time this site had ice passing across it. The ice was dirty, carrying a great deal of sand along with it, mostly concentrated at its base. The sand, probably mixed with a lot of silt and clay, actually polished the bedrock. It sanded it down and planed it off.

There was more. The glaciers carried with them a large number of cobbles and boulders. As these were dragged across the surface, they gouged scratches into the bedrock. Geologists call these glacial striations. We have seen such surfaces many times so it was hardly a great revelation, but it did speak clearly to us of the fact that there had once been a sizable glacier here. Then we saw more.

We looked up and there was Sam’s Point itself. It is another natural platform of quartz sandstone, but this one is bounded by a vertical cliff, a big one. Most people would enjoy it as a fine scenic overlook, but our eyes took us back into the Ice Age. Geologists call features like Sam’s Point scour and pluck topographies. These are common and each is the product of the passage of the ice. The Hudson Valley glacier advanced from the north and, as it crossed Sam’s Point, it scoured and striated that platform at the top of the cliff. That’s the scour part. Then, as the ice continued south, it stuck to the bedrock and then yanked enormous masses of it loose and carried them off. That left gaping scars in the mountaintop and one of them is the cliff of Sam’s Point. That is also the pluck part of this landscape. The cliff faces a compass direction of south-30 degrees-west. That, presumably, was the direction the glacier was traveling. We looked at the striations beneath us, and we had a compass. They had the same orientations.

Now we had a nice, coherent explanation for the topography of Sam’s Point. That’s what scientists call an elegant solution to a scientific problem. We would have been flushed with pride at having made such marvelous discoveries, were it not for the fact that thousands of other geologists had preceded us here, and they had, no doubt, all come to the very same conclusions.

Reach the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”