Poet’s Ledge -Jan. 20, 2022

A hike to Poet’s Ledge

Windows Through Time; The Register Star; Oct. 4, 2012

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

We wonder how many of you understand just how deeply philosophical we geologists can be. We tend to find ourselves drawn to some fine geological location; then we come to a pause in our rambles, and we drift, insensibly, into deep trance-like thoughts, usually involving images from the immensity of time.

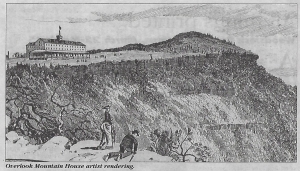

Well, it happens to us–all the time. One of our favorite locations for rambling into the past is a trek to “Poet’s Ledge” in Kaaterskill Clove. If that sounds like a nice place to hike to, then you are right. It’s a gorgeous ledge of sandstone, perched near the top of the eastern end of the clove. It has a spectacular view of this spectacular chasm. You gaze west, and you take it in–in its entirety. It can become a profoundly philosophical experience, an almost dangerous one.

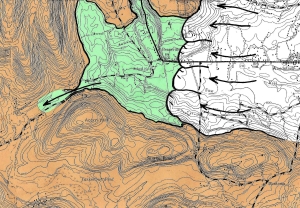

From up there, the clove is almost unblemished. You can see the highway that ascends it, but very little of anything else “civilized.” It’s almost pure raw wilderness from up there. We geologists gaze into the clove and see it as it developed, probably over the past 120,000 years. Much of the clove was eroded towards the end of the Wisconsin phase of the Ice Age. That was a time, between 10,000 and 18,000 years ago when the glaciers that had over-ridden the Catskills were in full retreat. They were melting away and enormous cascades of water must have been coming down the canyon of Kaaterskill Clove.

When we find ourselves at the top of Poet’s Ledge, it is impossible for us not to ponder such moments. We look up the clove and I see glaciers in the highlands. In our mind’s eye it is always an overcast day. The weather is unusually warm for the Ice Age, but this is the end of that time and warm is okay. The glaciers up there are gray on this cloudy day. They are totally disintegrating in the warmth. We always pick the day when the melting is at its all-time peak. Actually, we pick the very hour when the flow hits its maximum. When we are in a mind’s eye mood, we can do this sort of thing.

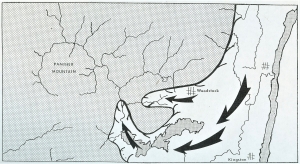

We look up the clove at that great high-elevation ice once again. Then we notice that, exactly where Haines Falls is today, there is a break in the ice. A roof has caved in right here, and we can see a massive current. It is an absolutely enormous fire hose of ice water. The flow comes from a hidden sub-glacial Kaaterskill Creek. It reached where the falls are today and then momentum carries it forward so that it could bore its way through the ice and create a great cavity. We gaze at the flow of water passing through that cavity.

Below, there is, once again, a roof of ice. Much of Kaaterskill Clove is still filled with ice. The creek is confined to a tunnel passing down the canyon beneath that ice. It is a very erosive flow of water and much of what we know as the clove today is being carved down there.

Across the clove is another flow of water. It pours off the mountaintop, just west of Indian Head. The water, up there, is visible, but it quickly disappears into another hole in the ice. There are two sub-glacial torrents in Kaaterskill Clove and now, for the first time, we notice and appreciate, and understand the terrible muffled roar that we hear.

The two sub-glacial flows form a confluence immediately below us, almost a thousand feet down. All downstream from here the roof of ice has entirely caved in. The torrent of water continues rushing down the lower canyon. Right now, the “Red Chasm” of Kaaterskill Clove is being given birth to by the powerful, raging, foaming whitewater torrents. From here echo’s a thundering roar, nothing is muffled about this sound. It deafens the ears.

This panorama from Poet’s Ledge is a horrifying scene of nature’s rawest power. The sights, the sounds, and the pounding vibrations all combine to make a jarringly terrifying scene. The pounding meltwaters are cascading, crashing, coming down the canyon with the power of a small asteroid.

And then it all ends; we have returned to the beautiful vista of today’s Poets Ledge.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”

Varves

Varves

Top of Comeau drumlin.

Top of Comeau drumlin. Comeau drumlin just right of center.

Comeau drumlin just right of center.