A Catskills wind gap, Part one

The Lackawanna River? Right here?

Windows Through Time

Robert and Johanna Titus

Have you spent much time in northeastern Pennsylvania? If so, then perhaps you have seen the Lackawanna River. It’s not one of the world’s great waterways, but it does count for something. It begins in the most northeastern part of Pennsylvania and heads southwest until it reaches a confluence with the Susquehanna River.

Did you know that it flowed right through Windham? Yes, the Lackawanna River. Well, it doesn’t flow through Windham today, but it very well may have a hundred million years ago. If it sounds like we have a lot of explaining to do, well we sure do. Carl Sagan said it best when he said “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.’ We are obliged to come up with a good story. Let’s give it a try.

For starters, let’s be sure to make it clear that the idea that the Lackawanna was a local stream is not ours. This notion was conjured up by one the many fine scholars that have worked at the New York State Museum these past two centuries. This one was named Rudolf Ruedemann. His career at the Museum occupied most of the first half of the 20th century. He was, more than anything else, a paleontologist and he produced many fine works on New York State fossils. But that didn’t stop him from working on other branches of geology.

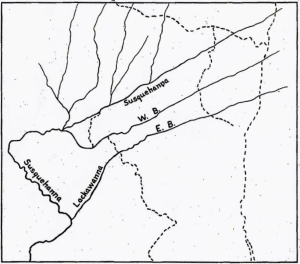

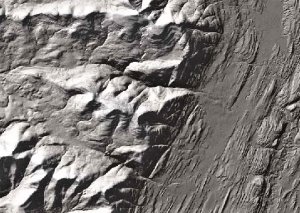

And that included river geomorphology, the study of river landscapes. Ruedemann must have had a way with spatial relationships, because when he looked at a map, he really looked at a map. Take a good look at today’s illustration. It is a slightly modified version of a map that Ruedemann published in the 1930s. Notice the prominent placement and labeling of the Lackawanna River. And then see how long he made the Lackawanna. Ruedemann meant his map to show local rivers as he thought they had been about a 100 million years ago. The East Branch of today’s Delaware River is what Ruedemann labeled at EB on his map. Ruedemann made it part of the Lackawanna. He does not label Batavia Kill but that is the eastern stretch of Ruedemann’s ancient Lackawanna.

Ruedemann had noticed how those three rivers all lined up so nicely. He hypothesized that they had once been joined together to form a very long Lackawanna. So, what changed all that? Why aren’t they all still joined? The villains in Ruedemann’s saga are the Delaware and the Hudson Rivers. The Delaware is the dotted line on the western part of his map. It, back then, was eroding its way north. It would get longer and longer until it intersected the old Lackawanna. Then it would divert much of that river. The upper Lackawanna became the East Branch of the now longer Delaware. The Delaware kept on eroding and eventually diverted the upper Susquehanna to make its West Branch.

River erosion like this is called headward erosion. The upper reaches, or heads of rivers, work their ways up into the hinterlands. If they encounter another river then they rob it of much of its flow. The word we geologists use for this sort of theft is “piracy.” Both the old Lackawanna and the old Susquehanna were pirated.

Ruedemann’s story is far from over. Look to the east on the map. Those eastern dotted lines are the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers, along with the Schoharie Creek. They too were the products of headward erosion. The Hudson, during the same span of time, had been eroding its way north. It gave birth to its tributary, the Mohawk, which, in turn, gave birth to its tributary, Schoharie Creek. And Schoharie Creek lopped off another large chunk of the old Lackawanna. That chunk is today the Batavia Kill drainage basin which flows right through Windham. That takes us back to the beginning of this column. The creek that flows through Windham used to be part of the Lackawanna River.

And that then gets us back to Carl Sagan. Did Ruedemann come up with enough extraordinary evidence to support his extraordinary claim? Well, to this day, that is something that they debate late at night in geology bars. Do we have our own opinions? Well, let’s just say that most couples fight over money. We are fond of Ruedemann’s ideas and we would like it if they turned out to be true. But even in the 1930s these ideas were conjectural. They can be, if one insists, dismissed as mere coincidence and who can say that is not so.

A longer version of this story will be in the author’s new book The Catskills, a Geological Guide, the expanded edition. Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”

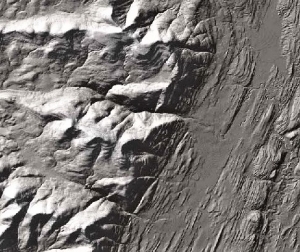

Hoogebergs – lower right

Hoogebergs – lower right