The Mountain House ledge May 17, 2018

Visions of a Hudson Valley geological past: “The Mountain House Ledge.”

Robert and Johanna Titus

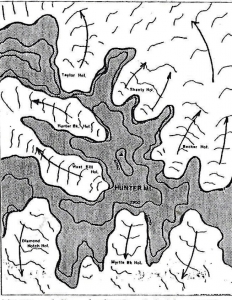

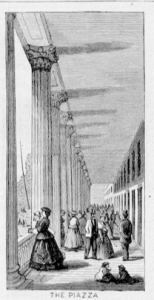

Certainly one of the most historic sites in all the Catskills is the Mountain House ledge at North/South Lake Campground. We are betting that most of you have been there. It’s a grand, broad shelf of sandstone, jutting out 2,000 feet above the floor of the Hudson Valley. It’s claimed that you can view some 70 miles of that valley from this site. It is, of course, the very place chosen for the building of the Catskill Mountain House Hotel, back in the 1820’s. That was the grandest of the grand hotels of the Catskills during our region’s most fashionable era. The hotel attracted a Gilded Age aristocracy; a Who’s Who of the American elite vacationed there. But something spiritual happened here too. America came to love nature at this location. It was here that the Hudson Valley School of art was born, when Thomas Cole spent a summer sketching the scenery. Almost equally distinguished was the poetry and prose that was inspired by this “sublime” wilderness landscape.

There is no way to overestimate the historical heritage of these few acres of land. The whole culture that we equate with the word Catskills had its birth at the Mountain House. And the hotel had its birth on this scenic ledge. It is one of our favorite places. We frequently go there and just sit upon the ledge’s rocks. We touch the sandstone and look around. All that lies above the ground, above those rocks, belongs to history. Here historians such as Roland Van Zandt and Alf Evers prevail. They explored the past at this site and recorded its many influences on our modern culture.

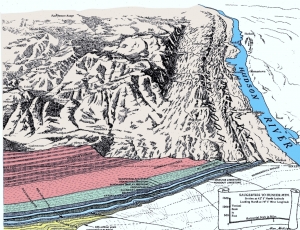

But, we touch those rocks again. Everything below the ground belongs to us! All around is the historical heritage of modern Catskills culture but below is a geological past that reaches back hundreds of millions of years. Nearly four miles of sedimentary rock lies beneath us – right here. And, down there, every stratum of rock has its own history, from its own time.

We touch this ledge and contemplate its petrified sand. It accumulated on the floor of a river channel. That was during the Devonian time period, about 380 million years ago. A river flowed by, right here, and then it disappeared off to the west. We gaze west and then turn around and look, more intently, eastward hoping to see where that stream and its sand came from. But . . . there’s nothing there but the great emptiness of the valley.

Suddenly, we are time travelers; around us it is the Devonian time period. We are just above the waters in the middle of that stream, looking east. To our left and right are the river’s low banks. Rising above them are Devonian trees, at least they must be trees; they are so exotic, so strange in appearance. Frail looking trunks rise 25 feet above the banks. There are no branches, not until the very top is there even any foliage. All this defies all efforts at description. There are no leaves, just things that might be called fronds. But even that term does not suffice. These are among the most primitive “trees” known to science. They represent evolution’s earliest efforts at the very concept of a forest, and Devonian evolution has not yet become very good at that. If these trees defy description, it’s because nothing like them grows today.

We turn and look east. In the distance a mighty mountain range towers above that horizon. We quickly realize that the Taconic and Berkshires of today are but the roots of this ancient mountain range. Their middle slopes are gun metal blue and cut by many enormous ravines. Above the blue is a horizontal white snow line. High above that are the white peaks of this enormous range.

Our journey into the past is a brief one. Soon we sit again upon the Mountain House ledge and see our modern landscape. We have beheld its geological heritage.

Reach the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.com. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”