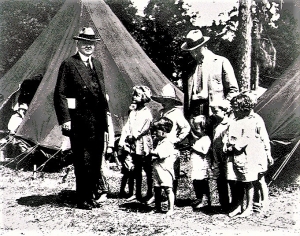

Herbert Hoover at Prattsville – Aug 11, 2022

Herbert Hoover–at Prattsville?

On the Rocks; The Woodstock Times 2019

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

Herbert Hoover doesn’t get much good press these days. He is largely remembered for not being able to end the Great Depression. Not enough people remember that, earlier in his life, he was able to feed and save the lives of millions of people in Belgium during World War I. He did the same in the Soviet Union soon after that war. He, it has been argued by some, saved more human beings from death than any other person in history. Hoover was a conflict of terms–a brilliant bureaucrat. We are fond of him, and his wife Lou too, for another reason. They were both trained in geology–at Stanford University (for Lou, an extraordinary accomplishment for a 19th Century woman). Herbert called himself a mining engineer, but he was, first of all, a geologist.

Can we do a little bragging? Geologists typically are given to have very good spatial relationship skills. We need them in our everyday functioning with the structures of rocks. We see through time too; we have to when we are dealing with millions of years of earth history. We geologists develop very structured ways of thinking and the two of us think we see that in Herbert Hoover’s biography.

For us, the best and most geological part of the story takes us back to the horrible flooding on the Mississippi in the year 1927. There had been extremely heavy rainfall over the winter of 1926-1927. By April the waters of the Mississippi were rising over the river’s levees at scores of locations. Hundreds of thousands of people were flooded out of their homes (largely poor and black). The highway and railroad infrastructures were being destroyed. It can be called the worst flood in the Mississippi’s history; it was a rampage.

There had, hitherto, been no real history of federal assistance for such emergencies, but federal help was needed. The governors of six southern states called for Herbert Hoover’s help. The engineer, Herbert Hoover was, after all, the world’s foremost disaster relief specialist. Somewhat reluctantly, President Calvin Coolidge appointed him chairman of a special cabinet committee. The committee had its first meeting – two hours later – and Hoover was in Memphis early the next morning.

Hoover assembled an enormous fleet of boats and airplanes to work the flooded river. He put together an army of military and volunteer civilian personnel to carry out what needed to be done. He built 154 refugee camps to house those displaced by the flood. He provided those refugees with health care, particularly the immunizations they would need. What Hoover did not have was federal money. But working with the Red Cross, Hoover directed a very successful fundraising effort. His emergency relief was, more than anything else, a volunteer effort. And it was a resounding success.

When we read the story of Hoover and the Mississippi, we thought back to our experiences at Prattsville, just two weeks after the Hurricane Irene flooding. We wanted to cover the story as both journalists and geologists but when we got to the Rte. 23 bridge at the eastern edge of town, we found the National Guard there. We were not welcome to enter Prattsville that day, especially as “journalists.” Well, we won’t tell you how, but we snuck in. But then, unfortunately, we still had to walk about a mile to get to where the cleanup action was going on. The Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) was there in force and had been for most of those two weeks. It didn’t take long before we saw evidence that an experienced team who knew what they were doing, had been hard at work. Each house we passed had been marked with a red X to indicate there were no people, especially dead people, inside. We passed a field filled with derelict cars. All had been towed there to get them out of the way. Another field was piled high with the flotsam and jetsam of flooding. Again, nothing was going to get in the way of FEMA activities.

When we got to the center of town, we found it buzzing with activity The National Guard was there too, in large numbers. And busloads of volunteers were arriving every few minutes, or so it seemed. People who had been hard at it for a while were covered with mud. We found a food service area with a sign that said they would feed anyone, any time, day or night–free.

We were most impressed.

Well, you probably see where we are going with all this. The ghost of Herbert Hoover was there in Prattsville. He had been something of a Teddy Roosevelt type of progressive Republican. Give the government a problem and watch and see if it can’t solve it. FEMA came long after Hoover (1978), but we think we saw his approach to the Mississippi floods at Prattsville. We speculate that Hoover’s 1927 efforts were, at the least, inspirational to today’s FEMA.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill geologist.”