A fossil Stream in Woodstock. Mar. 30, 2023

A Fossil River Runs Through Woodstock

On The Rocks, The Woodstock Times

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

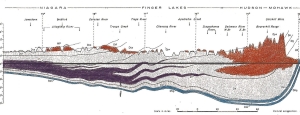

There is one very good thing about geology – you don’t have to travel very far to go see it. That’s certainly the case here in Woodstock. As we drove into town of Woodstock one day we stopped and took a long look at the rock outcropping at the intersection of Rt. 212 and Chestnut Hill Road. That’s just east of town. The rocks there belong to a unit called the Kiskatom Sandstone. They were deposited long ago as sediments on the outer edge of the great Catskill delta complex. Once again, the rocks took us back to a Devonian age Woodstock, maybe 380 million years ago.

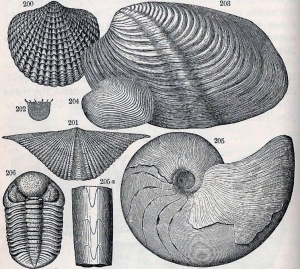

We knew the images that these rocks would generate in our imaginations. We could look east and, in our mind’s eye, we could see the towering profile of the old Acadian Mountains rising on that horizon. The Catskill delta lay below the mountains. It was an enormous expanse of fast-flowing and sluggish streams, with swamps, bayous, lakes and ponds. Here and there, we could see dense but primitive foliage’s of primitive plants. This was the setting in which the rocks of Woodstock had first accumulated as sediments.

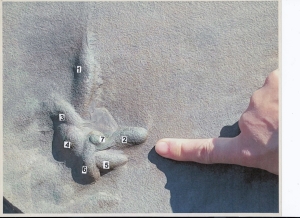

All this was vague imagination, but an outcrop is made up of real rocks and real rocks usually have very specific and often very interesting stories to tell. Here, at the Chestnut Hill intersection, there were two types of lithologies and two stories. The most striking rocks were the massive sandstones that made up the upper half of the exposure. Sandstones are just what they sound like, masses of cemented sand. These sands were deposited in strata which were inclined, first one way and then another. The sets of strata intersect each other in a pattern called “cross bedding.” From plenty of experience we knew what this meant. We were looking at sediments that had been deposited in one of those old delta rivers. The cross bedding formed as the sands were buffeted back and forth by changing currents associated with the rising and falling of the river’s flow. Each set of strata recorded an everyday moment in the history of that nameless old stream.

The finer grain deposits below the sandstones were different. They were more thinly laminated and composed mostly of silt and clay, now hardened into shale. Its color caught our attention, the shales were reddish. That’s a common color for rocks throughout the Catskills. This soft, brick-red is an indicator of terrestrial conditions, the shales had not been deposited in a river, but they had been the soils that formed on the banks and in between the streams.

When you go there, you will notice that there is a sharp boundary between the channel sandstones and the red soils. That’s not unusual, after all, rivers get to where they are by eroding through the surrounding countryside. This old river had cut its way through the Devonian flood plain soils.

There are ironies in the study of ancient rocks. We were acutely aware that the old river occupied the very space where the Saw Kill is today. Woodstock, then and now, was flood plain. There’s no relationship between the two rivers. They each occupied the same space, but they existed nearly 400 million years apart in time. Because of its age the old river may seem like an abstraction, or somehow less real than today’s Saw Kill. It’s not, in its time it was just as real as the Saw Kill is today. And 400 million years from now, both of them will be equally lost in time. That’s just the way it is. We, all of us, play out our roles on this planet and then disappear into time.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”