Vroman’s Nose in the Ice Age, 12-28-2017

Chapter 21 – THE VIEW FROM VROMANS NOSE

The Catskills in the Ice Age, 2nd edition. 2003

Revised by Robert and Johanna Titus

Dec. 29, 2017

FOR THE MOST PART, the towering slopes of the Schoharie Creek Valley are too steep for most people to climb. That’s too bad as there are a lot of good views up there. There is one place, however, where one of these heights is accessible. It’s a small hill with the curious name of Vroman’s (or, if you like, Vrooman’s) Nose. Vroman’s Nose, although small, is the gem of the Schoharie Creek Valley. It is one of the most prominent landscape features which appears as you drive Route 30 north from Breakabeen. The south-facing slope is a glacially plucked cliff, and the sloping plateau, capping the hill was carved by the scouring of passing glaciers. Glacial sculpturing may have occurred during all the glacial advances that crossed the Catskills, but the nose, as we know it today, is probably the product of the movement of ice toward the Lake Grand Gorge ice margin. The glacier we are speaking of filled the Schoharie Creek Valley. That was very late in the Ice Age.

Vroman’s Nose has been a “forever wild” refuge, open to the public and administered by a private

Rte. 30 to the left runs under Vroman’s Nose in the distance.

foundation. That might not have been, however. By the early 1980s, two houses had already been developed close to the summit, and there was talk of a motel or a restaurant at the very peak. Local people, including a number from the Vroman family, organized and raised the funds to buy the land, and to this day they have maintained the park.

On paper, it is the Vroman’s Nose Preservation Corporation that has run things, but in reality, it has been people like the late Wally Van Houten who have actually done the work. We met Wally at his home across the highway from the nose and he showed us the summit. A retired earth science teacher, Wally had a real appreciation for the old mountain, and he was proud of what his group had accomplished here.

The top of the nose could be reached by any of three trails. The red trail ran right up the face of the steep, south slope, a difficult climb for most people. The easy trail was the green one. It ascended the gentle western slopes of the mountain. Of course there is an intermediate trail, the blue one, which ascended the eastern slopes. We always liked like to go up the green and down the blue. Today the green and the blue trails make up the Vroman’s Nose Loop Trail.

The climb is well worth the effort. At the top is the “dance floor” with its spectacular view of the whole lower Schoharie Creek Valley. Make the hike on a warm, sunny afternoon in early autumn, just as the leaves reach their peak of color. You will not soon forget the experience.

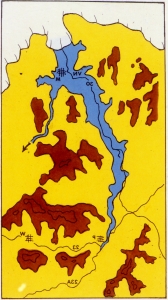

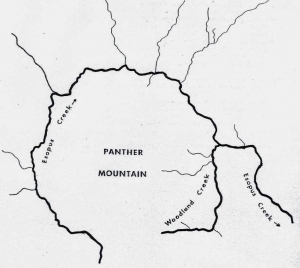

The geological aesthetics of the nose are there all year. Below, the floor of the valley is broad and flat. Read this landscape and you will find the record of the floor of Glacial Lake Schoharie. The story picks up as the glacier that had been damming Schoharie Creek, continued its retreat to the north, Glacial Lake Grand Gorge lay behind the melting ice and it expanded in the same direction. It is also likely that much of the ice in the various tributary valleys was also melting. All of the melting provide fresh meltwater, which continued to drain southward through the gap at Grand Gorge. But something important happened as the ice retreated to the vicinity of Middleburgh: a new drainage pattern became available. Meltwater was able to drain into Little Schoharie Creek and from there, into the upper reaches of Catskill Creek. While water had been draining through Grand Gorge Gap at about 1,600 feet, it could now drain into Catskill Creek at about 1,170 feet. Naturally, it did so.

also likely that much of the ice in the various tributary valleys was also melting. All of the melting provide fresh meltwater, which continued to drain southward through the gap at Grand Gorge. But something important happened as the ice retreated to the vicinity of Middleburgh: a new drainage pattern became available. Meltwater was able to drain into Little Schoharie Creek and from there, into the upper reaches of Catskill Creek. While water had been draining through Grand Gorge Gap at about 1,600 feet, it could now drain into Catskill Creek at about 1,170 feet. Naturally, it did so.

In a very short period of time the lake level dropped about 430 feet, and drainage through Grand Gorge Gap stopped altogether. Practically overnight, the upper Pepacton went from a raging, whitewater stream to a quiet, sluggish creek we see today. Meanwhile the lower Schoharie Creek saw the same 430 foot drop in the lake level. When all of this was completed, Glacial Lake Grand gorge had shrunk very considerable. In fact, it is not appropriate to use the same name for the smaller lake – the name for this one is Glacial Lake Schoharie.

Glacial Lake Schoharie

The history gets complex here. The climate fluctuated back and forth between warm and cold. The Schoharie Creek glacier retreated quite a way to the north and then readvanced once again (called the Middleburgh readvance), then it retreated once more. Through all this, Glacial Lake Schoharie expanded and contracted. Finally, the glacier retreated to the Mohawk Valley and the waters of the Schoharie drained off into the Mohawk River.

The interesting thing about Vroman’s Nose during this time is that the summit of the nose rises to about 1,220 feet and Lake Schoharie lay at about 1,170 feet. Thus the dance floor of today’s mountain and its steep cliff face must have formed a most beautiful cliffed shoreline on Glacial Lake Schoharie. And for a while, behind that lakeshore, Vroman’s Nose must have been Vroman’s Island!

Vroman’s Island, June 7, 13,505 BC, Just before dawn

The first glimmerings of dawn are showing above the eastern horizon, where the sky grades from a dark blue, high above, downward to a cream-colored horizon. Just off to the northeast looms the enormous wall of a glacier’s front. The upper facets of ice are high enough to be catching a lot of the early morning light, and they are bright with snowy whiteness. In between those facets, the ice is still dark blue. Below, the ice is dark and relatively featureless.

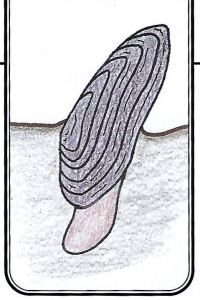

As the eastern sky lightens, the landscape begins to appear. It is actually a large, deep, frozen lake, mostly covered with a thick blanket of snow. To the west, the snow has blown up onto the shore, and then up onto the low slopes of the hill. That’s the case as far as you can see along the western shore of the lake. To the east however, the view is different. Here the whiteness of the lake’s ice ends abruptly, and a large channel of water can be seen. This channel is black in the dim morning light, but the blackness is interrupted by the clear images of white cakes of floating ice. The ice of Lake Schoharie has been melting and breaking up. A small armada of tiny icebergs is drifting to the northeast.

There are no animals, birds or insects anywhere in the vicinity. The air is absolutely still this morning, and there should be no noise whatsoever, but that is not the case. There is an intermittent creaking, groaning and sharp cracking from the glacier. Also there is a steady sound, a muffled roar, to the east, The dark current of water, with its drifting ice flow, is pointing the way to the source of this roar, a flow of water draining down the valley leading to Franklinton. Beyond Franklinton, are the upper reaches of Catskill Creek, and all the water of Lake Schoharie is pouring down that stream, eventually to enter the Hudson River.

The glacier is in full advance. Over the past several winters the weather has been mild and humid. Enormous amounts of snow have fallen upon the Laurentide Ice Sheet, off to the north. All this new snow has pressed down upon the glacier, and helped drive it southward, wedging it into the Schoharie Creek Valley. Beneath the glacier the warm conditions have produced a lot of meltwater. This has accumulated within the soft mud at the base, and the hydrostatic pressure of this water has given the ice just a little lift off of the valley floor. The glacier, in effect, has been hydroplaning down the valley at a remarkable velocity, up to ninety meters per day. Logically enough, this is called a surging glacier.

This is also a time of melting ice, and the results are predictable. The high wall of ice that makes up the front of the Schoharie Valley glacier towers above the thin cover of ice on the lake. Its steepness and great weight make it unstable and suddenly an enormous mass of wet ice gives way and crashes down into the lake. A huge volume of water erupts from this impact, and a single wave begins to radiate out across the lake. The wave faces a problem. The lake is frozen over and the wave is trapped beneath the ice. Soon, closely spaced, concentrically curved fractures appear within the ice, one after another, with immense cracking sounds. As the wave front expands across the lake each fracture opens up, a geyser-like hissing wall of water which erupts and splashes back down upon the ice. This continues until the wave reaches the other side of the lake and then, banking off of that shore, the wave front begins to advance down to the south. As it does more fractures appear.

Now the lake is a real mess. An enormous hodgepodge of floe ice is drifting back and forth, buffeted by the churned up lake currents. In an hour or so., the lake will settle down, but the current will continue to slowly carry all of the fresh floe ice toward the narrow Franklinton outlet. There an ice jam will already be forming and waters will begin to backup behind this dam. The flow down the outlet will slow to a trickle, and once again it will be quiet.

< Fig. 1 Fig. 2 >

< Fig. 1 Fig. 2 >

oove Kill, and you can park near it, get out and take a look. Here you can get your first glimpse of the ravine and actually think about ravines in general.

oove Kill, and you can park near it, get out and take a look. Here you can get your first glimpse of the ravine and actually think about ravines in general.