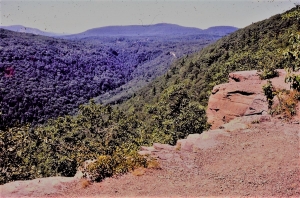

Inspiration Point in Kaaterskil Clove Aug 30, 2018

INSPIRATION POINT

On the Rocks

Oct. 17 1996

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

It doesn’t take much to get a geologist to go outside, but in autumn we find ourselves ever more drawn outdoors, especially as the season progresses. There is something compelling about the annual foliage scenery. There are only so many leaf seasons in a lifetime and to waste or miss one seems a sin. Each is something to be savored.

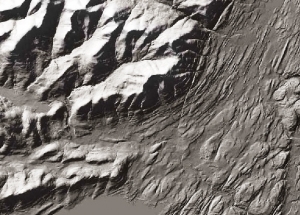

There are special places in the Catskills which we like to visit at any time of the year. One of those is Inspiration Point in Kaaterskill Clove. The site has been a favorite for Catskill hikers for more than 150 years, and there’s good reason. Inspiration Point towers above the rim of Kaaterskill Clove, a place which has often been referred to as the “Grand Canyon of the East.”

Take Rte. 23A to Haines Falls and turn east onto County Rt. 18. Turn right on Laurel House Road, and park at the end of the road. The new dirt trail will lead you to Kaaterskill Falls. But we want you to find the Blue Trail. (get a hiking map of the North Lake vicinity.)

The Blue Trail takes you south to the Layman Monument. Poor Frank Layman died there early in the 20th Century while he was fighting a forest fire. They have cut the foliage there so that his monument has a fine, but distant, view of Haines Falls. Beyond the monument, the trail turns east and soon brings you to the brink of Kaaterskill Clove itself. If you have not been here before, be prepared for a great surprise; Kaaterskill Clove is a lot bigger than you imagine. It’s about three miles long, a mile wide and a thousand feet deep. The slopes are steep, dropping those thousand feet in less than one half mile, and the visual impact of this makes the clove seem bigger than it is.

On an autumn day the clove is at its best, deep, rugged and picturesque. Hike eastward and the Hudson Valley soon comes into view. Continue along the blue trail and you soon pass some large rocky knobs which caught the eye of Thomas Cole. The renowned Hudson Valley artist painted at least one canvas right here. So did Sanford Robinson Gifford.

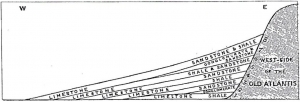

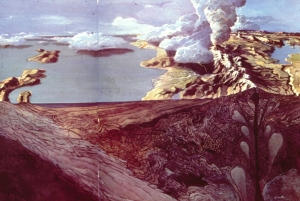

There is of course a geological story here. The great canyon is a relatively new landscape feature. A hundred thousand years ago, or so, the Hudson Valley was glaciated, filled to the brim with a stream of ice called the Illinoian glacier. This river of ice passed the escarpment of the Catskill Front which was, back then, unblemished by any large canyons. Only after the ice melted did Kaaterskill Creek form and start to erode its deep canyon. That makes the clove less than 100,000 years old. Big as it is, the clove is extremely young by geological standards.

Inspiration Point is just a little farther down the clove. Look for a fine platform with a cliff in front. People have found this the best place to take in the clove’s view. Landscape artists have seen the same. But Geologists have discovered that this is the best place to understand the glacial history of the clove. Look at that platform carefully; it has been scoured by the passing ice into a beautiful smooth polished surface. It’s only marred by the striations gouged into it by the passing ice. The cliff here is the product of glacial work. It faces westward and was formed when great masses of rock were broken loose and plucked away by the passing and westward moving ice.

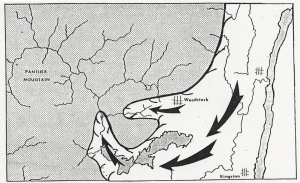

About 18,000 years ago the Hudson Valley witnessed another glaciation. Once again, a great stream of ice, the Wisconsin glacier, flooded the valley. This time some of the ice branched off and flowed westward up Kaaterskill Clove. This stream of ice would not stop until it reached nearly to Prattsville. It’s this ice that made Inspiration Point.

Gaze down to the bottom of the valley and then to the other side of the clove. Look up and down the valley. When you realize that all this was filled with moving ice you begin to get a sense of just how great an event this glaciation was. For a century and a half hikers and artists have come here to marvel at the landscape as it is; geologists come here and marvel as to how it was.

===================================================================

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.com. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”

Figure captions

“Raindrop prints” scattered across surface

“Raindrop prints” scattered across surface