Druid Rocks Nov. 8, 2018

Druid’s Rock

Windows Through Time

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

In the season of the summer solstice, Druids, or people who call themselves Druids hold celebrations at Stonehenge in England. Theancient rocks draw large crowds of Pagans and they often act that way; battles with police have been common. Throughout much ofEngland there are many locations where large monoliths rise vertically above the plains. There is little mystery about how these rocks got where they are; they were placed upright thousands of years ago by ancient Celts. Why they were erected is a different question and a bit of a mystery; reasons that have been debated for centuries. The only two things about them that are not mysteries are that they are eye-catching and intriguing, especially the large ones.

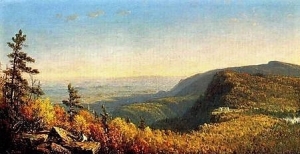

Few people know it, but we have some “Druid Rocks” right here in the Catskills and there is some mystery about them as well. The Druid rocks, the ones we speak of today, are found near the site of the old Catskill Mountain House Hotel at North Lake. Back in the days of the hotel, the surrounding forests had many paths that have since been lost to the returning forests. The old pathways led hotel guests past all of the interesting sights of the area and these included many large boulders.

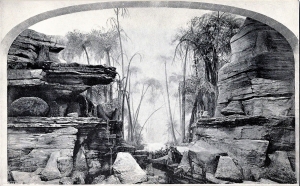

In the hill above the hotel there is a ledge, simply called “third ledge,” which is composed of a rock called puddingstone or conglomerate. The rock is made up of cemented gravel and cobbles. It is a remarkable rock and most fun to examine carefully. Third ledge towers above South Lake and along its edge there are a number of large boulders leaning against the wall. These are the Druid Rocks; the name was given because of their striking similarity with those of the Salisbury Plain. The old trails took people right past those rocks. Back in those days, they would have been much easier to get to and probably easier to explore.

Of course, there is at least one problem here; there were never any Druid cultures in the Catskills. Indians, who did live here, did not erect stone monoliths, at least not these ones. So how did out Druid rocks come to be? The answer most likely takes us back to the Ice Age. During an event called the Grand Gorge advance, about 18,000 years ago, there was a glacier advancing up Kaaterskill Clove. The ice thickened until it got so high that it flooded right out of the clove and expanded across South Mountain. When this sheet of ice got to the north end of South Mountain it plucked loose a large number of boulders and dragged them away. Plucking is a very common glacier behavior; the moving ice sticks to the bedrock and yanks it loose. When all this was well along, a great ledge of rock was created. The glaciers are long gone, but that ledge is still there and so are at least some of the boulders.

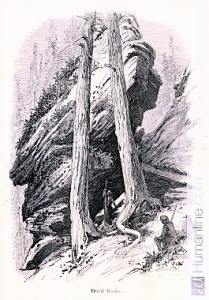

Plucking loosened boulders and dragged them off, but if the ice melted quickly enough, boulders could be plucked and left behind. Third ledge was plucked and some of its boulders were left behind. They are the Druid rocks. One, among them, is particularly impressive. It is an enormous rock. It stands almost exactly on end, just like the real Druid rocks of England. There is nothing terribly surprising about this. It’s just luck that left this one on end. Such a thing is unlikely but then, none of the other rocks come in this inclination. As we said, it’s just luck.

But it is also a very impressive rock. Getting there is not all that easy, however. First, go to North-South Lake State Park. At the southwest corner of the South Lake parking lot there is an unmarked entrance to an unmarked dirt path. If you can find it, you can follow its zig-zagging path up the hill, eventually to Druid Rock. From South Lake there is an old carriage trail that leads to the Hotel Kaaterskill site. Part way up the hill there is another path that branches off to the left (east). That path takes you right along the top of the old plucked ledge and eventually, it will lead you to Druid Rock. Big as it is, however, Druid Rock is well hidden in the forest so be patient and there is a real chance you may not find it at all. Half the fun is in the hunting. The very best thing to do is find someone who knows where the rock is and have them lead you to it.

================================================================

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”

Photo courtesy of Ralph Ryndak

Photo courtesy of Ralph Ryndak