Time lines in the Schoharie Valley – 4-6-23

Time lines

The Catskill Geologists

Robert and Johanna Titus

The Mountain Eagle 2017

Late at night in geology bars, we geologists ponder deep thoughts about what geologists call “deep time.” We would like to relate some of those thoughts to you in this week’s column. It’s an account of what we visualize when we drive south a few miles from Middleburgh on Rte. 30.

Any time of the year this is a scenic drive. Left and right, we pass beautiful agricultural fields. This is a remarkably flat landscape and much of it is fertile land; it has been farmed for centuries and all farmland is pretty. Then there are several scenic hamlets, including Fultonham and Breakabeen. We like to sometimes stop at the farmer’s markets along the way. This is the modern world that we are traveling through, and Rte. 30 provides a very nice view of it. When autumn is coming up; you should take this drive.

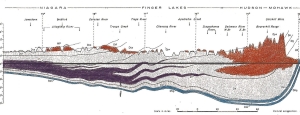

But, we are geologists, and we are always finding ourselves in the distant past. Did you read our recent column about this area? Then you know some of what we see when we do this drive. We related how this stretch of the Schoharie Creek Valley was once the bottom of an ice age lake. That was, perhaps 14,000 years ago when the ice age climate was warming up and the glaciers were melting away. We learned that this lake was hundreds of feet deep back then. If Rte. 30 had passed across that lake bottom then it would have been a pitch black road.

The next time you are there, stop and take a look around. We like to say that we are able to “savor” time at places like this. This broad flat valley floor has two manifestations in time. It is the world we see and that same flat surface was also the bottom of a substantial lake. This flat landscape has led at least two lives. You can imagine the thoughts this generates in a geology bar.

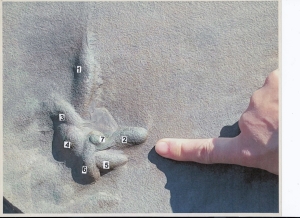

But, there is actually a lot more. When you explore the area, here and there you will encounter stratified bedrock. These exposures are mostly sandstones and shales, and it is not unusual for them to be rich in the fossils of marine shellfish. There are some substantial outcrops. One is at Vroman’s Nose. The next time you climb that “nose” watch for outcrops of stratified rock along the way. Drive south again and watch for more exposures along the way. It’s the same thing; those strata are frequently rich in fossils. Each stratum was formed on the bottom of a sea. It gets better; each stratum was the bottom of a sea.

Perhaps you are getting the drift of today’s column; we have been describing a single flat surface that extends south from Middleburgh. It is a surface that exists today and, in this form, it is a very scenic location. But there is so much more. This surface has existed several times in the distant past. It was, 14,000 years ago, the bottom of an ice age lake. It was just as flat then but under hundreds of feet of glacial meltwater.

Then there was that third time our surface existed. About 380 million years ago it was the bottom of a saltwater sea. Geologists call landscapes like this “exhumed.” As such they are landscapes that reveal episodes of time from the very distant.

We hope you will enjoy this ride in the country during the coming leaf season. Pull over, get out of your car and “savor” our geological history.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”