Visions of the past 7 – The Mountain House ledge

Visions of an Art Trail past – The Catskill Mountain House site.

On the Rocks

May 23, 2013

Robert and Johanna Titus

There is one single location in the Catskills that fully deserves the word “legendary.” Many of you, we hope most of you, will guess correctly that this is the Catskill Mountain House Hotel site. It is site eight on the Hudson River Art trail. The Mountain House was first constructed in 1824 at a location that had long been known as Pine Orchard, high atop the Catskill Front. The ledge the hotel sat upon had long attracted visitors, lured by the sweeping view of the Hudson Valley. It was thus a natural choice as a place to build a resort hotel. But the very notion of a resort hotel was a novel idea back then. Not surprisingly the hotel was a big success and it became a legendary hotel on a legendary site.

It was not long before artists were attracted to the hotel. Thomas Cole came late in the season of 1825. A soon to be legendary artist was at the legendary hotel. It was all fated to be. Cole would produce a painting of the hotel, but that canvas has been reported as lost. His sister, Sarah Cole, did one too, possibly a copy of Thomas’ work, and it survives. You can easily find images of it online. Our favorite image of the hotel in its early years is a picture by William Henry Bartlett. As a mass produced print, it is something that we could not only find, but also afford to buy – and it is a nice picture.

Curiously the great view always defied efforts to paint it. It is simply too sweeping to place on one canvas. We only like one effort: Frederic Church’s Above the clouds at sunrise, 1849. We think that when it comes to “painting” the Catskill Front, it is the writer who can do best.

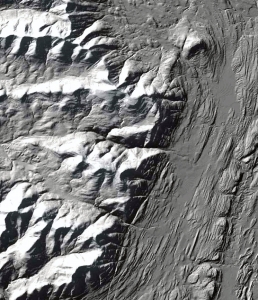

When we visit the Mountain House site, which is frequently, we gaze out at the view and fully appreciate that everything we see out there, absolutely everything, was shaped by the glaciers. It is a notion that is almost overwhelming for its impact. We are looking at something that James Fennimore Cooper’s old leatherstocking, Hawkeye, called “all creation” and all that creation was at the hands of the glaciers.

When we stand in front of the Mountain House site we can look about and still trace the outline of the hotel from where its foundation stones had been placed. We can feel the presence of history here and that can be overwhelming. But, when we face north, into the Hudson Valley, our mind’s eyes take us into the deep past of the early Ice Age:

——————————-

We have gone back more than 20,000 years and we have arrived at a moment in time just before the effects of the Ice Age will be manifest. The valley in front of us is filled with dense primeval forests. All of those tree species are familiar to us; they are oaks and maples and birch. There are a lot of chestnut trees too, and we wish they were still around today, but there is nothing unfamiliar about them.

We are the mind’s eyes and we can drift forward through time. Centuries pass and we begin to sense that things have been changing. The summers seem cooler; we just don’t see those blistering hot days that we used to. Oddly, the winters seem warmer and always very cloudy. It seems to always be about 30 degrees out and snowing, always snowing.

Summers don’t bring all the warm weather birds that they used to, and when they do arrive, it is later in the spring. They disappear earlier in the autumn. We are puzzled and disquieted. Had we kept records we would have found out that we were right. Summers are cooler, bird migrations have changed. But . . . why?

The years and decades pass by and now we notice that the trees up above look unhealthy. Even in August their leaves look pale and small. We climb up and see that they are. Next, we notice that the snow is melting later and later in the spring; the snows are arriving earlier in the autumn. We are perplexed; what is causing all this?

We notice changes in the type of weather; there are stretches of days when the blue skies stay completely free of clouds. A cold dry wind blows, continuously, out of the northeast. We look in that direction and we begin to guess that there is something out there. It must be cold and dry – but what could it be?

Now the forests up above begin to die. Worse, the malady of small pale leaves has spread downhill and the trees below us are turning sick. What is going on? We look up above and now the forests at the top of the Catskills appear to be dead. Even in August it looks like November up there. Our fears and our confusion turn into near panic. We have ancestors in Europe who actually did see this sort of thing. Did they ask the shamans what was going on? What answers were they given?

The cold dry winds continue. The dead trees suffer further indignities. First the twigs dry out and fall. Then the branches and even the limbs do the same and the heavy winds rip them to the ground. The Catskills forests are now dead; nothing but naked trunks still stand. Soon all the birds and insects are gone; it becomes so quiet – so desolate.

Now we look up the Hudson Valley to the north. There, as far away as we can see, there is something. It is dark blue in the morning; it turns green and then yellow as the morning sun rises, and it is brilliantly white at noon. In the afternoon the colors are reversed. What is going on? Months and perhaps years go by, we really can’t tell, and that object, or that material seems closer. Eventually it is close enough; we see what it is and, in a flash, all our questions are suddenly answered.

It is a glacier that has been moving south and starting to fill the whole expanse of the Hudson Valley. An ice age has arrived.

Nobody ever painted this scene.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”