Noah’s Flood and the Catskill Sea

Noah’s Ark and the fossils of the Catskill Sea

On the Rocks; The Woodstock Times, 2019

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

In recent columns we have been defending our science against the views of what are called young earth creationists. These are people who see our planet’s geological history in ways entirely different from the views of conventional geologists, including the two of us. Creationists see the world as being about 6,000 years old. Geologists have determined that it is about four and a half billion. You might think that modern science would easily be able to determine which view is more accurate. We think that it has; creationists disagree. But they do recognize that they have problems. They need to explain thick sequences of sedimentary rocks so they see them as a record of a single catastrophic event, the legendary Noah’s deluge. We geologists look into the past and we see sedimentary rocks deposited, not in a single flood, but in a wide variety of ancient sedimentary environments, each similar to ones seen today. Again, you might think that modern science could deal easily with such discordant views.

We geologists go on to look into the fossil record and see life that was different from what we see in today’s world. We see fossil assemblages that are representative of what lived during specific chapters of the distant past. In truth, we are not sure that we understand what creationists see when they look at the very same fossil records and that is the focus of today’s column.

We always like to say that if any professional geologists found themselves at an unfamiliar but fossiliferous outcrop, it wouldn’t take them long to come up with a fairly accurate determination of when those rocks had been deposited. That’s because trained geologists have had the experience needed to recognize Cambrian fossils, or Jurassic fossils, or Tertiary ones — and so on. All geologists are just plain comfortable with fossils from various chapters of earth history. That, of course, includes the two of us, but what we are especially good at are Devonian fossils; we have seen so many of them, mostly here in the Catskills and, much of the time, while writing for you.

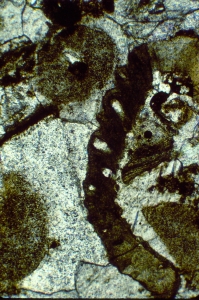

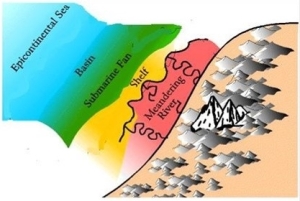

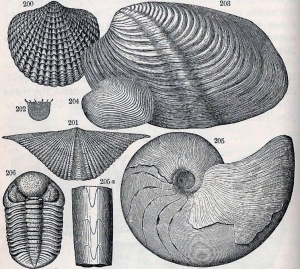

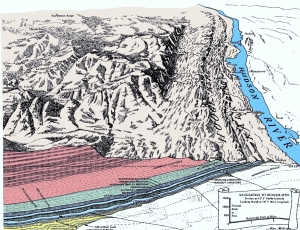

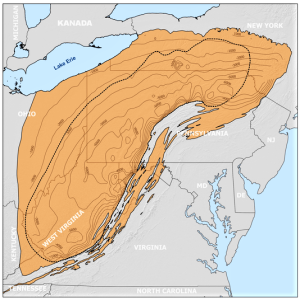

Take a look at our illustration. It’s from a 19th century geology textbook and shows typical marine shellfish fossils of Devonian age. That’s a time period running from 419 to 369 million years ago and that’s the age of all the rocks here in the Catskills. Those fossils speak to geologists of a time when all of our region lay beneath the waves of a shallow sea, sometimes called the Catskill Sea. Strata, often rich in these fossils, can be found in the lower ledges of the Catskill Front. This is nothing less than a petrified ocean with a rich fossil record of its long ago inhabitants.

Our illustration shows Devonian species. Some of them, such as the two clams in the upper right, have a familiar look to them; the rest are truly exotic. The three shellfish in the upper left are called brachiopods. Today, brachiopods are nearly extinct, but they were enormously abundant in all Devonian seas. The shellfish in the lower right is an ancestor of today’s Nautilus. Nautiloids are another nearly extinct group. It’s the trilobite on the lower left which is truly bizarre. These creatures have been gone for a quarter of a billion years. All in all, we are looking at an assemblage of animal species that are all primitive and/or extinct. But, more importantly, they are an assemblage that virtually any knowledgeable geologist would recognize as being Devonian.

Geologists of the 17th and early 18th centuries were puzzled. Back then, most geologists assumed that all fossils were deposited by Noah’s deluge. So why then was a typical fossil assemblage always composed of extinct species and only extinct ones? All species, they reasoned, had been created during creation week. So, while many might have been killed off during the flood, shouldn’t there be a fair sprinkling of modern and, indeed, living forms in all fossil records? Geologists and biologists needed a scientific theory to explain this problem.

The Darwinian theory of evolution solved that problem; almost all fossils are of extinct species because they are from so very long ago. They have simply been passed by in a progressive history of evolving life. They have had the time needed to become extinct and to be replaced by newly evolved forms.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.” Read their blogs at “thecatskillgeologist.com.”

1

1  2

2 3

3