Radiolarians Dec 26, 2018

Stories in Stone

Invasion of the Radiolarians

March 2007

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

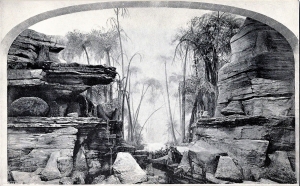

Mt. Moreno might be considered a nondescript little hill in southwestern Columbia County, it is just not all that noticeable a landscape feature. There is one road that curls around it and you have to know where that is, or you will miss it altogether. There are some very nice views of the Hudson River on this hill but not much else to attract people.

But we are not “people,” we are geologists. If you drive on Mt. Moreno Road along the western fringe of Mt. Moreno, you will notice some pretty nice outcrops here and there. Continue south on Rte. 9G and you will see more. There are stories in these stones and good ones too. It turns out that Mt. Moreno is very well known to New York State’s geological community. It is the site of one of the greatest “infestations” in our region’s history.

Thick Normanskill sandstones and thin shales

If you do drive past Mt. Moreno, you might decide to pull over and take a look. The rocks are stratified, and they are largely dark, almost black sandstones and shales. This is the Normanskill Formation. But there is more; there are horizons of chert here too. Chert is better known by the word “flint.” Flint is a shiny dark rock which was used by Indians and other stone-age cultures to fashion into stone implements. You have, no doubt, seen some very fine arrowheads and can appreciate the skill that went into making them.

Flint is an extremely fine-grained rock and that’s why it breaks into small curved chips. An experienced craftsman could pound away at the rock and shape it pretty much any way he wanted, and that includes points, hammers, scrapers and axes. But just saying that the rock is fine grained does not do it justice; there must be much more. That’s where we get to our infestation.

Long ago, in fact about 450 million years “long ago,” our Hudson Valley region lay at the bottom of a very deep marine trench. Do you live in the Hudson Valley? It is hard to believe, but right where you are now was probably 20,000 feet, or more, deep, lying at the bottom of the ocean. Take a look out of your window and see the bottom of the Marianas Trench. Imagine very cold temperatures, strange fish and unbelievable high pressures. But mostly imagine it as not being dark as much as completely black. That’s right here, long ago. The time is called, by geologists, the Ordovician.

This marine deep was called the Normanskill basin and it is a very important part of our geological heritage. A land mass, as large as the islands of Japan, was colliding with North America and the crumpling, associated with this collision, helped make the deep basin. There were no fish, but in every other respect, this was a Marianas like trench.

There were volcanoes and probably many of them. Volcanic eruptions produce silica-rich soot, which can rain down on the seas. There waters would thus be very well supplied with silica (SiO2). That is not especially good for most organisms, but it is very good for radiolarians.

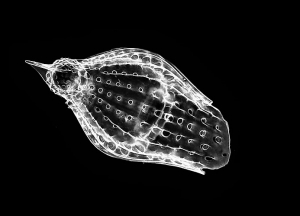

Typical radiolarian

If you have never heard of radiolarians, then you are not alone. They are a group of microbes that are mostly unknown to the general public. You might call them protozoa as they are single celled creatures with animal affinities. They are still alive today and they have tiny skeletons composed of silica.

Silica can be hard to find in sea water, it is not very soluble. But after a sizable eruption, the silica content could sky rocket. Those were the good times for our microbes; they had what they needed to make more of themselves. Volcanic eruptions may very well have been followed by enormous population blooms as astronomical numbers of radiolarians appeared.

None of them lived very long and soon, large amounts of silica skeletons were falling to the bottom of our Normanskill Trench. Thick deposits of them piled up in ever thickening accumulations. Radiolarians might have been very small, but hundreds of feet of radiolarian sediments were piling up.

Burial is nearly forever; these deposits have spent almost the entire last half billion years at Mt. Moreno. They have been deeply buried, under an enormous weight of rock for all of that time. What would you look like after a couple of hundred million years of crushing weight? Well, our radiolarians gradually saw that pressure crush them and harden them into that rock we call flint.

So, now you know a lot more about Mt. Moreno than ever before. Do take a look at those shiny flint deposits along the highway. These rocks had a “previous life” as microbes in a very dark cold ocean.

=============================================================

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”

Rte. 209 outcrop

Rte. 209 outcrop

Mix of black shales and sandstones

Mix of black shales and sandstones