Through Time at Kaaterskill Clove 4-2-25

A Journey through time in Kaaterskill Clove

The Catskill Geologists – The Mountain Eagle; 11-3-17

Robert and Johanna Titus

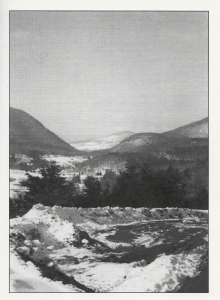

Have you ever hiked the north rim trail at Kaaterskill Clove? It’s one of those many great experiences that anyone living in the Catskills should have done – perhaps, like us, many times. Better still, it’s something you should take visitors to see. When we go there, we stop at Inspiration Point and look down about a thousand feet or so, and gaze into the distant past. Way down there, about 15,000 years ago, was a raging, foaming, pounding, thundering, whitewater torrent. Those were the waters of the melting glaciers of those late ice age times. That flow did most of the work of carving Kaaterskill Clove. That’s what makes this truly a geological wonder.

But there is still an older time, represented down there. Down in the very depths of the canyon, there are stratified sandstones and shales. The canyon is about a thousand feet deep here, so there must be an equal amount of stratified rock. Those rocks are middle and late Devonian age, which makes them about 385 to 375 million years old – that’s in very round numbers. It’s natural for geologists to ponder such vast numbers. We are pros; we are professional scientists, and we are not supposed to wax poetic about such things, but – we can’t help it.

The two of us began to wonder just how many years had passed by from when the oldest strata, at the bottom of the Clove were deposited, to when those at the top came to be. We got out some publications from the New York State Museum and began to make some “guesstimates.” We are only going to make some gross approximations today; so don’t hold us to any of our numbers. We just want to give you a notion of when all the stratigraphy at Kaaterskill Clove came into being, and how long it took to be deposited. If somebody thinks they can come up with better numbers, we welcome them.

We think the strata at the bottom of the canyon belong to a unit of rock called the Plattekill Formation. The Plattekill is a unit of gray and brown sandstone. The New York State Museum places the middle Plattekill at about 385 million years in age. We think the top of Kaaterskill Clove corresponds with the top of the Oneonta Formation, a largely red sandstone, and that makes it about 381 million years in age. The math is pretty easy; we get about 4 million years of time represented from the bottom to the top of the clove’s stratigraphy. Remember those 1,000 feet that the canyon encompasses? Well, we divide through and we get about 4,000 years per foot of stratified rock.

Now, none of this is great science, and none of it is great math. A foot of river sandstone might have been deposited in a few hours. A foot of red shale may have taken many, many thousands of years to form. There must have been sediments from vast expanses of time that were eroded away and lost forever. Other great lengths of time just never saw any deposition at all. But, we think we have come up with some reasonable approximations and that is all we are aiming at.

Again, stand atop Inspiration Point and look down those thousand feet. See 4,000 years of time for every foot below you.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The

ts, and we are always finding ourselves in the distant past. Did you read our recent column about this area? Then you know some of what we see when we do this drive. We related how this stretch of the Schoharie Creek Valley was once the bottom of an ice age lake. That was, perhaps 14,000 years ago when the ice age climate was warming up and the glaciers were melting away. We learned that this lake was hundreds of feet deep back then. If Rte. 30 had passed across that lake bottom then it would have been a pitch black road.

ts, and we are always finding ourselves in the distant past. Did you read our recent column about this area? Then you know some of what we see when we do this drive. We related how this stretch of the Schoharie Creek Valley was once the bottom of an ice age lake. That was, perhaps 14,000 years ago when the ice age climate was warming up and the glaciers were melting away. We learned that this lake was hundreds of feet deep back then. If Rte. 30 had passed across that lake bottom then it would have been a pitch black road.