Some life or death fossils March 26, 2021

Some life-or-death fossils

On the Rocks – The Woodstock Times

Robert and Johanna Titus

If you want to get into a good debate on a college campus, then raise up the issue of consciousness. What is consciousness? When did it evolve? Even – does it actually exist? Most of the debates center on people. Do you think that you are conscious? We know people that would quarrel with that. The two of us are just a bit too busy for all this, but we would like to raise a similar issue today. Do clams have consciousness? Clams? Consciousness? Does that sound like an issue that would only turn up in an On the Rocks column? Quite possibly so let’s get on with it.

First of all, one of us, Robert, is a paleontologist; the other, Johanna, is a biologist so we have some first-hand experience with clams, including having dissected some of them. Clams have nothing much that resembles a central nervous system, so it would seem that they could not have any level of consciousness. They cannot be deep thinkers (or even shallow thinkers!).

But we are familiar with some clam fossils that raise some doubts about this. And they are right here in the Catskills, perhaps near to where you live. Take a look out the nearest window. If you live anywhere near Woodstock, then there was once the top of a great delta out there – the Catskill Delta. That was about 400 million years ago. It would have reminded you of today’s Ganges River Delta in Bangladesh. As in Bangladesh, rivers, some of them very large, flowed by – right in your neighborhood. There were floods in those rivers too. Take a look at our first photo. It shows a sequence of Catskill bluestone strata. These are matched by a lot of other bluestone sequences, all throughout the Catskills. Those bluestone sands were deposited in those Devonian age Catskill Delta rivers. They were commonly flood deposits. They conjure up images of powerful stream floods, carrying great masses of sand in their dirty waters. That was during the flood, but then the flood currents subsided. Slowing flow currents cannot carry very much sediment, so those sands were quickly deposited. They, much later, hardened into sandstone. There is nothing unusual about any of this.

But keep looking. See those two vertical structures. What on earth are those? We see these, also all through the Catskills and they have attracted a lot of attention. Geologists have determined that they are fossil clam burrows. They were dug by clams who were working their ways upward through those flood sands, probably right after the floods had passed.

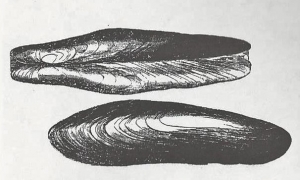

The clams, themselves, have been found and they belong to a genus name Archanodon. See our second illustration. This was a relatively common clam, living in the many streams that crossed the old Catskill Delta.

We have seen a lot of these and typically these burrows are found in flood strata measuring two to three feet in thickness. When we are looking into the past, we see that these flood sands must have posed quite a problem for our clams. When you are a three-inch-long clam, suddenly buried in three feet of sand, then you have a problem. Fortunately for our clams, they were well equipped to deal with this problem. They had large and strong burrowing muscles (curiously, they are called “feet”) that enabled them to work their ways upward. That’s where these burrows came from. They are called escape burrows.

If clams can be gregarious, then Archanodon was. They lived together, in large numbers, on the floors of their streams. When the floods struck, they were all buried together. Each one faced the same life-or-death decisions. They could dig, or they could die. They dug. Our photo shows the escape burrows of two clams, but at this outcrop there are dozens more. Every member of this colony went to work digging itself out. They seem to have always succeeded; we have never found one only halfway up.

Well, that gets us back to our initial question: do clams have consciousness? Did our clams experience fear? Did they have any awareness of what had befallen them? Did the actually decide what to do? We really don’t know. We suspect that they may well have been equipped with some sort of automatic response system that allowed them to deal with what should have been a scary situation. We guess that we will never know for sure. We will bring this up for debate the next night we are in a geology bar – or at a faculty meeting.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.” Read their blogs at “thecatskillgeologist.com.”

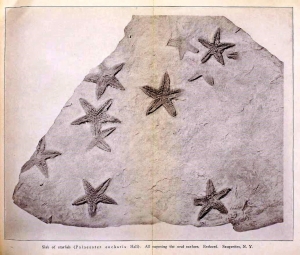

e Rev. Cole found and collected one slab, particularly rich in fossil starfish. He sent it off to the State Museum, and that quickly generated a lot of interest. It wasn’t long before Museum staff ascended Mt. Marion and located Cole’s starfish ledge. It must have involved a great deal of hard labor, but some 200 square feet of that sandstone ledge were eventually uncovered. This would have represented a large swath of Devonian age sea floor. About 400 specimens of starfish of the species Devonaster eucharis were collected from it. Many of them were found in a fine state of preservation. They give us a very clear picture of their anatomy. Altogether, this was a most remarkable discovery.

e Rev. Cole found and collected one slab, particularly rich in fossil starfish. He sent it off to the State Museum, and that quickly generated a lot of interest. It wasn’t long before Museum staff ascended Mt. Marion and located Cole’s starfish ledge. It must have involved a great deal of hard labor, but some 200 square feet of that sandstone ledge were eventually uncovered. This would have represented a large swath of Devonian age sea floor. About 400 specimens of starfish of the species Devonaster eucharis were collected from it. Many of them were found in a fine state of preservation. They give us a very clear picture of their anatomy. Altogether, this was a most remarkable discovery.