John Burroughs birthday blog Mar. 29, 2019

Burroughs’ Boyhood Rock

Poughkeepsie Journal

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

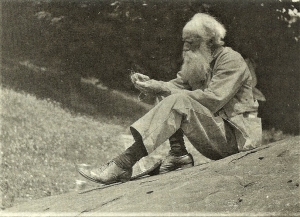

Every rock has a story within it that can be read if you just know how to. As geologists, we know that this is so. Like so many of us we learned, long ago, how to read these tales of the distant past. So, it was no surprise that, upon visiting “Boyhood Rock,” we found a story worth repeating. This is certainly one of the Catskills best known rocks. It’s at Woodchuck Lodge, John Burroughs’ hideaway home in the western Catskills. Burroughs was the beloved turn of the 20th Century nature writer. His boulder is on his old family farm. He spent many an hour sitting upon it, gazing at its magnificent view and pondering the natural history all around him. Best known for his writing about birds, Burroughs, especially late in life, was an avid amateur geologist. He understood at least part of the story of Boyhood rock. He knew that the boulder was a glacial erratic. There is a photo of him, proudly pointing out to Charles Edison the nearby glacial striations.

The boulder is from the Oneonta Formation which makes up the local bedrock of the upper Pepacton Valley. The Oneonta sandstones are, for the most part, river deposits of the old Catskill Delta. The fossil delta is very well known within the geological community; it was an enormous complex of streams that originated in the Acadian Mountains in what is western now New England. From there these rivers flowed westward down into the Catskill Sea of today’s New York State.

There was a problem, however, that bothered us for a while. We were puzzled by the many small holes that littered the boulder’s surface. At first. we guessed that these were fossil animal burrows. Could these be the burrows of Burroughs rock? Alas the gods of nature writing would not be that kind to us. No, they just did not look right for burrows. Eventually, we found an especially well-preserved one and quickly recognized it as the cast of a fossil tree root. They were fossils of the Gilboa trees from one of the world’s oldest fossil forests. These were tropical plants, and so Boyhood Rock, a product of the ice age, must have had an older, equatorial ancestry.

Gilboa tree roots are common in the Catskills, but it was the first time we had ever seen them in a river sandstone. How could trees have been growing in the channel of a fossil river? In science, the solution of one problem often leads to another. A possible answer is that this stretch of the old channel had once been a great bend in the river. During an especially bad flood, the river carved a new route and the old bend was abandoned, leaving a large, curved lake called an oxbow. The lake gradually filled with sediment, and then trees began to grow, their roots penetrating the old river sands. That’s what we see today.

But there was another mystery that bothered us a lot. There are three boulders here, all of which match each other in terms of lithology, and all have fossil tree roots. This can’t be a coincidence as the odds are too great; the three rocks must once have been joined. Our guess is that there once was a much larger Boyhood Rock, transported not beneath a glacier but within it. As the ice melted this boulder was lowered toward the ground. Stresses generated at this time caused the original rock to break up into the three pieces, each of which “landed” near each other and remain as we see them today.

And, so it was that Boyhood Rock gave up its geological secrets. There is a great deal of satisfaction that comes from cracking a scientific problem, even if it is a problem of absolutely no practical significance.

___________________________________________________________________

Contact the authors at rndjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”