Time in Winter: The Catskill Front again

Windows Through Time

Revised by Robert and Johanna Titus

Daily Mail Feb. 2011

Last year, about this time, we gazed up at the Catskill Front. That‘s a good thing for a geologist to do this season of the year. Winter is when it is so easy to see the ledges of rock that make up the stratigraphy. With all the leaves down we can see a lot more geology, and that is good. But some readers have written and asked us about some of the numbers we cited. We claimed that there are about 9,000 feet of strata up there and some astute readers wondered how that could be. After all, the Catskill Front only rises to about 3,000 feet at the top of places like North Point. “Where are the other 6,000 feet of rock?” they ask. Good question.

Well, fair enough, and the answers to their questions leads us to something important about the whole Catskill sequence. First, let’s document our estimate. We asked Dr. Charles Ver Straeten, of the New York State Museum, about this and he confirms that there are eight or nine thousand feet of strata in the Catskill Sequence, depending on exactly where you measure. Plenty more strata have eroded away over the eons. These strata begin at the bottom of the Hudson Valley and stretch up to the top of Slide Mountain. Dr. Ver Straeten has spent many years studying this sequence; his opinions carry a great deal of weight.

But, how come all these strata don’t’ rise up higher over the landscape? How come we don’t have Catskill Mountains that tower a full 9,000 feet? The answers to those questions take us back to the processes that created the Catskill Sequence and the Catskill Mountains themselves. We have to travel back about 380 million years of so, to a time when the Catskills first formed. Back then North America had been enduring a great collision with a landmass which you might call part of Europe. The collision led to the uplift of all of Northern New England and the creation of a mountain range called the Acadians. This event is known to geologists as the Acadian Orogeny.

We have talked about this in several columns. Weathering and erosion of the Acadian Mountains produced the sediment that eventually formed the Catskills. But there was a lot more than just sedimentation going on. There was plenty of real warping of the rocks. The notion of deforming rocks may well be a novel one. How, on Earth, can rocks be deformed? They are, after all, pretty rigid materials. And they are very stable too; at least that’s as it would seem.

Well, rocks certainly are rigid, stable entities, at least under the normal circumstances that we are all familiar with. But most rocks have been around a very long time and they have had many long “journeys.” Our Catskill rocks are mostly a little less than 400 million years old and that was plenty of time for them to have gotten into a lot of “trouble.”

By that we mean that our rocks have seen themselves buried under thousands of feet of other rocks–many thousands of feet. Look up at the Catskill Front and imagine that great thickness of strata rising high above it. That rock would weigh a great deal and the weight we speak of is what allows much of the deformation. Imagine how you would feel if several thousand feet of rock were pressing down upon you. But there is more.

Our rocks suffered deformation in another fashion. They were there when North America experienced the worst of that continental collision. Again we have to use our imaginations. Try to envision what it is like to be “hit” by another continent. If Europe slowly collided with North America the pressure of the impact generated would be truly enormous.

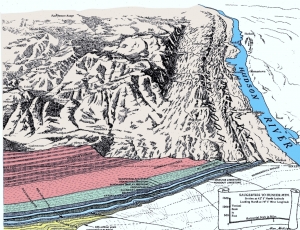

Now we have seen two processes ganging up on our poor rocks: first there was the weight of burial and then there was the shove of a massive continental collision. The effect of each, individually, would be enormous, but we want them to be occurring at the same time. That’s, in fact, what happened. As Europe collided with North America, it generated a massive uplift and tilting within the whole northern Appalachian realm. Those mountains, the Acadians, eroded away and their sediments buried our Catskill region under thousands of feet of sediment. It was compression, however, that had the better of it. “Europe” pressed in from the east, shoved our Catskill sequence, and then tilted the strata into a broad incline. Incredibly, later in time, Africa collided and all this was repeated. It is such monumental tilting that allows about a mile and a half of strata to make a mountains range only 3,000 feet tall. See our illustration.

Tilted strata of the Catskill Front – Courtesy of Alan McKnight![]()

Reach the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.” Watch for them in the Mountain Eagle, the Woodstock Times and Kaatskill Life.