Yellow alert

The horrible snowfall this middle March was bad enough but it sets us up for serious flooding.

If there is an intense all that snow will turn into floodwaters.

If there is a heavy warm rain storm it will only be worse

This happened in 1995 and it could happen again.

This 2012 Kaatskill Life article explains the problem

****************************************************************************

Alluvial fans, everywhere

The Kaatskill Geologist

Robert Titus

Kaatskill Life magazine

2012

Science, it is said, is self-correcting. Scientists have a reputation of being intelligent people, but that does not mean they do not make mistakes. That is why it is the nature of scientists to be skeptical; we always challenge established concepts and sometimes, not often but sometimes, we overturn them. This column has done something of this sort ever since Hurricane Irene struck the Catskills. The Catskill Geologist has long argued that many of our regional villages were safely perched up atop ice age features called alluvial fans. Rising often 25 feet or more above flood plain levels, it always seemed that such villages were far too high up for floods to ever reach them. Sadly, Prattsville proved this whole concept to be a false belief. It thus seems that it is appropriate – even necessary – to devote an article to the issue of alluvial fans and reevaluate the hazards associated with them.

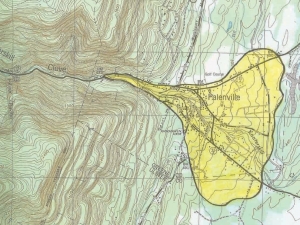

I have gotten all the maps out, and looked through the Catskills in hopes of developing a much broader view on this issue. My thoughts have been developing as I have written several recent Kaatskill Life articles. Now it is time to summarize these into something scientists call a “synthesis.” I thought that it would be wise to start by identifying the best example of a fan anywhere in the Catskills. That turned out to be easy. It was the fan I first noticed decades ago. This emblematic alluvial fan is the one at Palenville, located at the very bottom of Kaaterskill Clove. A fan is called a fan because its shape looks like the sort of fan a lady would have carried back in the 19th Century. We can go to Palenville and see a splendid example (fig. 1) and come to clearly visualize an alluvial fan and how it formed.

fig. 1. Alluvial fan at Palenville.

Kaaterskill Clove and its fan formed during the Ice Age, probably during one or more of the great melting events that terminated major phases of glaciation over the course of the last two million years. One likely time occurred about 130,000 years ago, at the end of the Illinoisan Stage of glaciation. For nearly 200,000 years North America had endured the advance of various ice sheets. These swept south and covered much of the continent. But now the climate was changing and the ice was finally melting away. We can only imagine how much meltwater was pouring out of the high peaks of the Catskills at that time. A lot of it came to be funneled into a canyon located where Kaaterskill Clove is today and this began the erosion that would create that great scenic wonder. All this was likely repeated about 14,000 years ago when the younger Wisconsin Stage of the glaciation came to an end. Again, enormous amounts of meltwater must have poured out of the mountains and down the growing clove. Thus there were possibly two great episodes of glacial meltwater pouring out of the mountains. These resulted in the creation, deepening and widening of Kaaterskill Clove to its present state.

But, there is more. You have to understand that where today there is the empty space of a clove, back before the Ice Age there had been bedrock. Stand at a location like Inspiration Point, towering above the clove, and imagine all that space below you having once been filled by bedrock. Think of how much meltwater was needed to erode away all that rock in order to create the clove. It’s an awesome notion. But – all that eroded bedrock has been turned into sediment – where did all the sediment go?

Fig. 2. Alluvial fan at Palenville.

We can actually go and see that sediment. If you have the opportunity to fly south along the Wall of Manitou, the Catskill Front, then you can see it. That sediment makes the Palenville alluvial fan (fig. 2). The Palenville fan has its highest elevation right up at the mouth of Kaaterskill Creek. It displays a gentle incline, sloping to the east and “fanning out” from the mouth of the creek. You can get a closer look at the fan deposits while driving up Rte. 23A in the clove itself. Just downhill from Fawn’s Leap a heap of these sediments are visible down at the bottom of the canyon (fig. 3).

fig. 3. Alluvial fan sediments in Kaaterskill Clove.

We learn a lot about the origins of alluvial fans at Kaaterskill Clove, but not much about their flood threats. Palenville was established and built on its fan, but it has never faced any serious flood problems for reasons that we will have to deal with soon. Let’s learn more by looking at some other towns lying upon other alluvial fans. Naturally the place to start is at Prattsville.

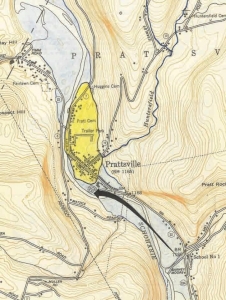

fig. 4. Prattsville and its alluvial fan from air.

Prattsville (fig. 4) had its origins way back at the end of the Ice Age. There was a moment in time when this stretch of the Schoharie Creek Valley was at the bottom of something called Glacial Lake Grand Gorge (light blue on figure 5). That lake flooded the valley, but only temporarily. It owed its existence to a glacial dam, far to the north, and when that ice dam melted, the lake drained. This stretch of the valley became dry, with only an early version of Schoharie Creek flowing through it. But Huntersfield Creek descended the slopes above and it, like Kaaterskill Creek, brought sediment with it. Soon an alluvial fan formed (fig. 4 & yellow on fig. 5). It was much smaller than the one at Palenville, but it did serve as a location for the establishment of another town. It is easy to imagine pioneers arriving at the Prattsville site and deciding that this was the place to build a town. After all the land, here, rose a good 25 feet above the level of the river. They must have thought that they would never EVER have to face a flood.

fig. 5. Alluvial fan at Prattsville

There is a real irony here. What attracted settlement was a supposed safety from flooding. In reality that safety was an illusion. The alluvial fan, which should have elevated Prattsville above the flood, instead made things worse, much worse. Look at how wide the blue part of the valley south of town, which is upstream. Now look at how narrow the valley floor is adjacent to Prattsville. As it passed by Prattsville the flow was impeded by the alluvial fan. Water, from behind, shoved it forward. The flow was squeezed and forced to rise up and flood into town. I am making an analogy to the garden hose. When you squeeze its nozzle its power increases. You are only washing a car, but Schoharie Creek, with its fan, did much the same in destroying a town. I call this the “garden hose hypothesis. I am arguing that it should be applied to all of the Catskills. We found exactly the same when Johanna and I did an article about Margaretville (Kaatskill Life, spring 2012). This town too, was established upon an alluvial fan. Exactly the same garden hose effect helped damage that town.

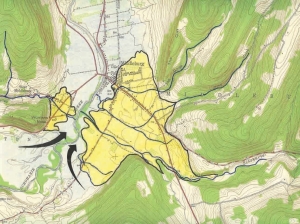

Since these revelations occurred it has become critical to take another look at all the towns and villages of the Catskills and see if the same threats can be found. They can, and this needs to be understood. What happened in Prattsville may serve as a model for all of the Catskills. Let’s look at Middleburgh (fig. 6). It was badly flooded by Irene and now we can understand why. Most of Middleburgh, like Prattsville, lies upon an alluvial fan that partially blocks the Schoharie creek Valley. To make things worse there is another, smaller fan across the valley (fig. 6).When the floods arrived, the garden hose effect caused rising, squeezing, and speeding up of the waters; the town suffered grievously. So too was the effect of an alluvial fan at the town of Schoharie. There another fan, lying just north of the town, impeded the flow of the Schoharie Creek. That “squeezed the hose” and flooded the town.

fig. 6. Two alluvial fans at Middleburgh

Windham, at first looked like an exception. Here the valley of the Batavia Kill appears to be too narrow for an alluvial fan, but something akin to one did form here. I was puzzled by Windham; there was no fan there. But I found that, back in the 1930’s, geologist John Lyon Rich had solved the problem for me. He found that Mitchell Hollow Creek, which flows south into Windham, had an interesting history. Back in the Ice Age, Windham lay at the bottom of a glacial lake. Mitchell Hollow Creek flowed into the lake and deposited a delta into its waters. The top of a delta is flat and elevated. Like the alluvial fans, it attracted development, and all of Windham is built upon it. But Batavia Kill was forced to carve a small but narrow canyon through that delta (fig. 7), so the delta behaved like a fan during Irene. Waters were squeezed by the delta sediments; currents were raised and speeded as they careened through Windham, hence the awful flood that occurred there. Windham, like Margaretville, has a long history of flooding; now we understand why.

fig. 7. Batavia Kill at Windham

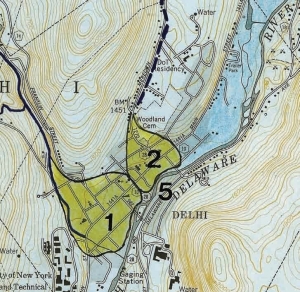

But now we must look farther, to towns that did not suffer from Irene. There, the floods did not hit, but the threats remain. Let’s look at Delhi, the subject of another “Catskills Geologist” article (Summer, 2011. It is a two alluvial fan town (fig. 8). What would happen to Delhi if very heavy rainfall fell upstream from it, say at Stamford? The garden hose hypothesis would bring a horrible flood into that town.

fig. 8. Two alluvial fans at Delhi

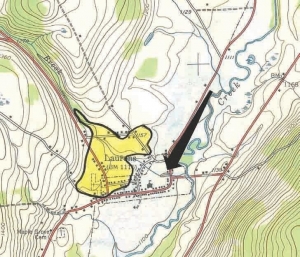

Then there are Milford and Laurens (fig. 9), in the western Catskills. Each is perched upon a similar fan and each would face certain flooding if only enough rain fell upstream from them. These towns did not suffer the fate of Prattsville because it did not rain enough upstream from them. There are good reasons why we might think that such heavy rain might never occur on this stretch of the Susquehanna, and so those towns may be safe. The heavy rains of Irene were associating with a weather pattern that climbed up and over the steep topography of the Catskill Front and that is a real rain generator. No such obstacle is found near these other villages, and so it is not obvious that such an awful event could occur near them. But . . . Nature loves to surprise us.

fig. 9. The alluvial fan at Laurens.

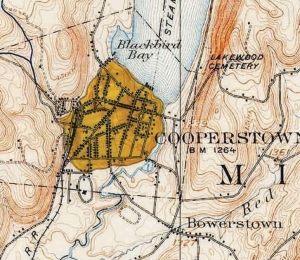

It gets worse. Cooperstown is built upon still another alluvial fan and this one stretches across almost the entire Susquehanna Valley (fig. 10). It nearly blocks that valley and that is what happens when you really put your thumb on the nozzle of a garden hose and squeeze it. That has left a very impressive canyon for the Susquehanna to flow through (fig. 11). The top of the Cooperstown alluvial fan rises about 60 feet above the river and it will be very difficult for flood waters to ever rise that high. But what if there is a very, very heavy rain just off to the north. Suddenly enormous amounts of water would be squeezing into a very narrow canyon. It would be expected that those waters would quickly climb the walls of that canyon and . . . then what? The Bassett Hospital complex lies at the top (fig. 11). All this is nearly unimaginable; it’s just nearly impossible for such rainfall to occur, but “nearly impossible” is not impossible.

fig. 10. Alluvial fan at Cooperstown.

The purpose here is not to promote horrible fears. Instead the purpose is to rationally come to understand what potential flood threats there are in our region. Many of our villages were constructed upon alluvial fans. They date back to times when nobody event knew what such a fan was. They just seemed to be logical places to settle, apparently safe from flooding. The problem is that Prattsville has shown us otherwise.

fig. 11. Susquehanna River at Cooperstown. Bassett Hospital Complex on left.

I do not propose that we dismantle Delhi, or Milford or Cooperstown. But, I do argue that we should understand the nature of the landscapes we live upon. They can offer us dangers we never dreamed of and we should recognize those dangers. Many climate scientists fear that powerful storms, like Hurricanes Irene, Lee, and Sandy, will become more commonplace. If they are right then there is much to fear: hazards such as we have never faced before. My message is mostly aimed at zoning boards. They should realize that there are places where homes and other buildings just should not be located.