Sailing Across the Catskill Sea – Aug. 7, 2018

Sailing Across the Catskill Sea

The Catskill Geologists

The Mountain Eagle; 8-7-18

Robert and Johanna Titus

We are both now officially retired, so we are supposed to be doing a lot of traveling. Right? Well, right, but if we are off traveling then how are we going to research all of these articles that you enjoy reading? The answer is that we always bring a camera along and whenever we see something geological, we take its picture and write a column. Let’s begin today. We are just back from a trip to East Aurora in western New York State. We went to see the Roycroft Community. That was one of the many social communities that sprang up all across the country during the 19th Century. This one, founded by Elbert Hubbard, specialized in the production of Arts and Crafts furniture and artistic printing. It thrived for a number of years and then, like so many others, it faded away. It didn’t help that Hubbard and his wife went down with the Lusitania. You can look it up in Wikipedia and learn all about it. Or, you can follow our lead and go for yourselves.

There wasn’t much geology there, so most of our photos were taken along the way, heading west on the New York State Thruway. We traveled north to get to the Thruway and then, heading west, left the Catskill region. Soon we began to see outcrops, along the highway; they were very different than what we see in our Catskills.

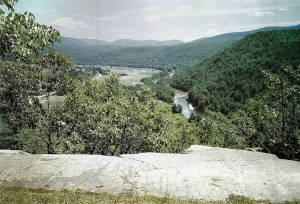

Throughout the Catskills we see brick-red sandstones and shales. They are the deposits of the great Catskill Delta, a terrestrial setting. During the Devonian time period, a little less than 400 million years ago, this huge delta was spread out across much of which is New York State today. But, as we traveled to the west, we saw those red strata replaced by a mix of gray and brown sandstones and shales. These were, obviously, something very different. We pulled over a few times and looked. It didn’t take long for us to find the occasional fossils of invertebrate animals—mostly marine shellfish. We had “arrived” in a whole new and different ecological setting.

Well, we knew a lot about this before we had embarked on our journey. We knew that, lying offshore of the Catskill Delta, had been something called the Catskill Sea. It was a broad, open but rather shallow ocean. It’s well known to geologists all over the world for its rich, diverse and well-preserved assemblages of fossils.

We continued west on the Thruway, but now we were living in two worlds at the same time. In front of us lay upstate New York, a picturesque landscape at the height of summer with all of its rich foliage. But, left and right, we were passing outcroppings that took us back in time to when there had been an important ocean right here. Such are the privileges of being geologists.

==================================================================

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.” Read their blogs at “thecatskillgeologis.com.”