Glacial Lake Woodstock – June 10, 2021

A cold bath for Woodstock

The Woodstock Times; On the Rocks; Dec 11, 2008

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

We have, off and on, over the past year or so (2008-2009), been journeying through Woodstock’s ice age history. In this column we would like to slow down a little and try to focus on one of the more interesting aspects of this saga: the story of Glacial Lake Woodstock.

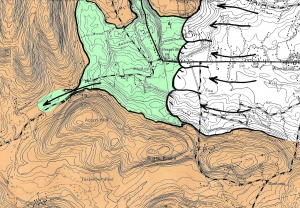

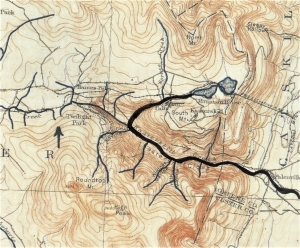

Lake Woodstock was first discovered during the middle 1980’s. It was described, briefly, in a State Museum report, but not much work has been done on it. To date, it has only been recognized as a relatively small lake, mostly just to the east of today’s town. It was, we think, much bigger than that. we have been poking around the area and we are now convinced that the lake stretched all the way to Bearsville. It deserves a lot more investigation than it has gotten. Let’s do some of that today.

We have, in an earlier column, claimed that most of the area west of Woodstock formed on the bottom of the lake, and if you travel west down Tinker Street and look to your left and right, you will see the old lake floor as an extensive flat landscape. But there is more, much more. In fact, this all gets to be very interesting to a geologist.

Our descriptions so far, have been of the first Lake Woodstock. There was a second one and that is where we want to take you today. That first Lake Woodstock formed when a glacier, lying just to the east of town, was damming the Saw Kill Valley. The ice dam blocked the flow of the Saw Kill and that created the lake: the first time.

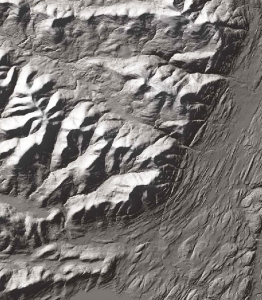

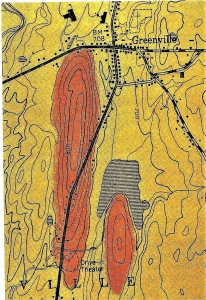

The climate warmed and the glacier retreated back to the northeast and there is a good chance that the first Lake Woodstock drained off to the south. But the Ice Age was a very complex time; its climate was constantly shifting. Under such circumstances a warm period with melting can be replaced by another cold period with a re-advance of the ice. That is what happened. Take a look at the satellite shot. If you view it carefully you will see that the landscape has a streamlined look to it. That streamlining was sculpted by the re-advancing ice. You can actually “read’ the movement of the ice. It advanced out of the Hudson Valley, from the upper right-hand side of the photo, and pushed on westward. we are not sure how far it got, but we can see streamlining at least as far as west of Bearsville. That means that much of the Saw Kill Valley was, once again, filled up with ice. In fact, when we look at this image, we can convince ourselves that the hills, south of Woodstock are smoothed off and streamlined, more than is the case for the taller Overlook Mountain, to the north. We are guessing that the ice actually overran those southern hills. It seems to have been a major advance of the ice.

We wonder how long such an event takes, but we will never know. And we wonder how long the ice remained, clogging the Saw Kill Valley. we will never know that either. But, given enough time, the climate warmed and the ice retreated from the Saw Kill, one final time. Once again, the remaining ice formed a dam, and that dam blocked the Saw Kill and created the second Glacial Lake Woodstock.

Take another good look at that satellite shot and you will see the flat landscape in the Bearsville area and again, just south of Woodstock. There is still more flat landscape in the area east of Plochman Road. All these landscapes are the floor of Glacial Lake Woodstock. It was pretty big.

One logical question is how deep was it? we alluded to that in a column earlier in the year. we believe, that in the Bearsville vicinity, this lake was at least 280 feet deep. If you are reading this somewhere near Tinker Street, we would like you to look out the window and up those 280 feet and “see” the ice water here. Once again geology has a way of rearranging your sense of reality. Carl Sagan had something to say about notions such as this. He said that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” Providing the evidence for the 280-foot claim will be our responsibility in the next column.

Contact the authors at randjtitusr@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”

t it occasionally in Woodstock Times columns over the years. The unit of rock has recently become very important.

t it occasionally in Woodstock Times columns over the years. The unit of rock has recently become very important.

Drumlin field

Drumlin field  Drumlin

Drumlin Two drumlins, see symmetry and shape.

Two drumlins, see symmetry and shape.