Regression to a Mean 1-14-21

Regression to the Mean

On the Rocks –

The Woodstock Times, June 17, 1999

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

We live in a world where we are used to the idea of rising sea levels. During hurricane seasons, we expect to see the rising of the ocean’s waters and the flooding of coastal landscapes. We may not be comfortable with the idea of coastal erosion, but we do see it as the “norm.”

Few of us would recognize it, but this is a bias. We are comfortable with the notion of rising sea levels not because that actually is the norm but because we live in a world where the climate has been warming up ever since the end of the ice age. As the climate has warmed glaciers have melted, and meltwater has poured into the seas raising their levels worldwide.

There is, however, nothing actually inevitable about rising sea levels; it could be the other way around. Suppose that the climate was cooling down. Then ice would be forming, water would be withdrawn from the sea to make the ice and the sea levels of the world would be dropping. Throughout the length of Earth history, it must be that there have been as many times of dropping sea level as there were risings. Neither is favored over the long term.

A rising sea level is often called a transgression while a falling sea level is called a regression. Transgressing seas do leave coastal regions susceptible to storm flooding and damage. Such coasts are prone to erosion and, in fact, do erode away.

Regressive coasts are quite different; as the sea levels drop rivers bring sand and mud into the seas and pile them up. The coasts advance seaward. We call that progradation.

You and I are not likely to ever see a good regression, not unless there is a dramatic shift in the climate. So, we will never see a whole coastline prograding. But we can go back in time to eras when the seas were retreating and see the results in the rocks. From Woodstock, travel east on the Glasco Pike to Mt. Marion. There, where Plattekill Creek crosses the road, you will see a towering outcrop. It is mostly black shale. The rock was once black mud deposited in relatively deep waters of the Devonian seas, a little less than 400 million years ago.

The black shale is a fine-grained deposit of mud. Mud accumulates in very thin sheets at the bottom of a quiet sea. The sea was quiet because of the great depths. There were no currents, or tides or waves in the deep water. But look upwards; at the top of the exposure, you will see a number of thick-bedded strata. If you could get up there you would find that these are sandstones. Overall, the outcrop grades from shale to sandstone, from mud to sand. That’s the regressive sequence.

What was happening? At this time the Acadian Mountains, located where the Berkshires are today, were actively rising in a dramatic and important mountain building event called the Acadian Orogeny. As these mountains uplifted, they began to weather and erode. Large masses of rock were converted into even larger volumes of mud, sand and gravel. That’s the fate of weathering rock. Mountain streams transported all of this material as sediment into the adjacent sea. That’s us right here, Woodstock and the whole Hudson Valley region were under water. Marine currents sorted out all of the fine-grained muds and carried them far out to sea where they settled to the bottom as the black muds that hardened into our black shales.

But as mountain building continued gluts of coarse-grained sediment overwhelmed the muds and layers of sand began to pile up Thus, when this sediment hardened, we ended up with the shale to sandstone sequence. That’s a regression.

Go back westward on the Glasco Pike. You will soon encounter other outcrops. These are mostly more sandstones. At the top of the hill, you will even see the cross section of an old river channel. The regression had succeeded, it had transformed a sea into a land area. There should be one of those New York State historical markers up there. It should say “Here the Woodstock area rose out of the sea.” After all, that was an historical event.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”

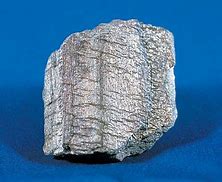

Phyllite

Phyllite

Austin Glen to the right.

Austin Glen to the right.