Manorkill Falls – June 29, 2023

The Depths (?) of a sea,

The Catskill geologists,

The Mountain Eagle, Dec. 1, 2017

Robert and Johanna Titus

Have you ever been to Manor Kill Falls? You take Rte. 30 to where it intersects Rte. 990-V and then you head north a few miles and then watch for the signs. They have a fine parking lot and then you have a choice of trails. The upper trail heads for the top of the falls, but we want you to take the lower trail. That one takes you down to the bottom of the falls where you get a fine scenic look at it. That’s where the best geology is too.

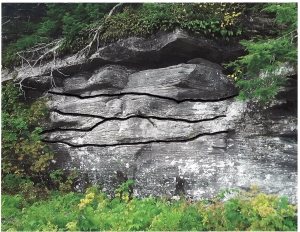

You stand at a good location and look up at the falls. If you have an eye for rock types then you will recognize a sequence composed mostly of thinly bedded black shales. These strata are interrupted with the occasional dark sandstone. That’s a good start but now you need to get a better look at these rocks. You can do that by looking down; the ground is littered with rocks. A thin “shingle” of black shale will reveal a very fine-grained sedimentary rock; it is composed of silt and clay. None of those grains are large enough to be seen. It is black from all the organic matter in it – the stuff of ancient life.

It is natural for a geologist to begin looking for fossils. Those provide the clues for figuring out exactly what kind of environment is represented here. The hunting was disappointing at first but, after a short while, the fossils of some shellfish were turned up. These were creatures called brachiopods. Like clams, they have two shells, and like clams, they spent all of their lives lying on the seafloor. But they are not clams; they have a very different anatomy, so different that they are not even distant cousins of clams.

Nevertheless, these brachiopods are marine animals, and they tell us that all the strata we are looking at were formed, about 390 million years ago, at the bottom of something that is often called the Catskill Sea. Stand back at look up again. Each horizon of stratified rock once took its turn being the floor of that ocean.

Well, now we know something important; The Manor Kill Falls location was once the bottom of a large ocean. The next question that comes to mind, to a geologist anyway, is “just how deep was this ocean?’ We can’t throw a plumb bob overboard so just how do we determine this important bit of information. The answer is that we don’t, we can’t. But we can make some approximations.

Here’s how we do that? We have already looked those lithologies over and we have found that most of the bedrock here is fine grained black shale. That’s a type of rock that forms in relatively deep waters. The black color speaks to us of a relative scarceness of oxygen on that sea floor. That black biologic material would have decayed away if there had been oxygen. We did not find many fossils so not too many shellfish lived down there.

We thought we were building a case for a very deep-sea environment, but then we found something else. That something else was downstream. There we saw a slab of rock covered with what are called ripple marks. Take a look at our photo. These are slightly asymmetrical ripples and that indicates that these were sculpted by currents passing across that sea floor. What does that mean? Ripples are rare in very deep waters. It means that this seafloor was not all that deep.

We stood on that slab; we were literally standing on the bottom of an ancient sea. We looked up and, in our mind’s eyes, we could see the dimness of just a little sunlight that had reached down to this seafloor. It just wasn’t that deep.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.” Read their blogs at “thecatskillgeologist.com.”