Rip’s Rock- Jan 27, 2022

Rip’s Rock

On the Rocks; The Woodstock Times

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

One of the nicest hikes along the front of the Catskill Mountains is the trek up the Old Mountain Turnpike. Today the turnpike is just a hiking trail, but in the 19th century it was one of the region’s most important highways. It was the dirt road that transported carriages up the Catskill Front to North Lake and into the Catskills beyond. Many of the people who made this journey were on their way the Catskill Mountain House Hotel. The trip up the mountain was a tough one, for horses and people alike, and so, not surprisingly, there was a small halfway house along the way. Coaches stopped and passengers could refresh themselves while horses rested a bit. This was the old Rip Van Winkle House.

New and better roads left the old highway obsolete and abandoned. But today you can still follow the old turnpike. From Rt. 23A in Palenville, head up Bogart Road and watch for Mountain Turnpike Road. Turn left (west) and at the end of this road is the trailhead and parking. After about a 45-minute hike you will reach a dramatic hairpin turn in the trail where it crosses a mountain stream. That’s the site of the Rip Van Winkle House, just a little bit of foundation remains.

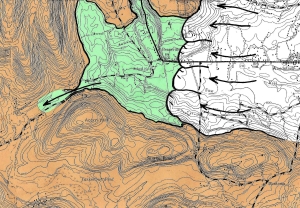

We enjoyed this hike just for the pleasure of it, but I had some geological interest as well. On the map of this area is labeled “Rip’s Rock.” Whatever that might be, it piqued our curiosity and we wanted to find out more about it. The best topographic map we could find showed a great ledge and we wanted to find out what its geology was and maybe also answer the question of how it got there. The problem was that Rip’s Rock was a full 600 feet straight up, not quite a vertical cliff but a pretty steep incline.

Actually, there was one other problem: there are about a dozen or so smaller ledges between the Old Mountain Turnpike and the great ledge of Rip’s Rock, each one, it seemed, was determined to slow down our climb. They did, but eventually we found ourselves at the base of the last and greatest ledge, Rip’s Rock itself. It took a while, but we found a cleft in the ledge and access to the top.

Reaching the top of any great ledge is one of the great experiences of the Catskills. It’s something like rising to the surface of the sea after a deep dive. As your head emerges above the top of Rip’s ledge the whole sky opens up, especially to the east, as the panorama of the Hudson Valley appears. Below is the ravine that cuts into the mountain. Its formal name is “Rip Van Winkle Hollow.” Stony Brook, the mountain stream here, has been cutting into the Catskill Front since long before the last glaciation. In part, that’s why Rip’s Rock is here; the ledge was left behind by the erosion of that mountain stream. It’s the top or lip of the canyon.

But there is much more to the story of Rip’s Rock. We soon found the evidence that we had suspected since we first gazed upwards at the ledge. The exposed bedrock, up at the top, has been ground and polished by the passing of ice. More than anything else Rip’s Rock is a monument to the ice age. From about 22 to 14 thousand years ago there were several episodes when masses of ice passed across the ledge. The ice acted like sandpaper and ground the ledge into a smooth surface. Cobbles and boulders dragged along added gouges or striations into the surface. Also, the moving ice adhered to the bedrock and yanked loose very large blocks. This, more than anything else, left the jagged cliff that we see here.

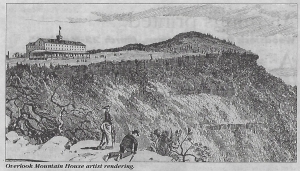

Rip’s Rock is a feature that we have seen before in these columns. It’s called “ramp and pluck topography.” The ramp is a gentle slope ground into the top of a hill by passing rock while the pluck is the jagged front left when the ice yanked loose its large rocks. We see them in many Catskill locations. The ledge at the top of Overlook Mountain is the nearest example. So too, are the Palenville Overlook and Pratts Rock in Prattsville. We have talked about all of those in past columns.

Rip’s Rock is a great hike with a wonderful vantage point at its top. You can stand at the top and gaze out into the breadth of the Hudson Valley. But as we said, this is also a monument to the ice age. When you stand there atop the Catskills you must imagine a few thousand feet of moving ice above you. It’s the Hudson Glacier slowly moving down the Hudson Valley. In the darkness you can hear the groaning and grinding sounds punctuated by sharp cracks. Every once in a while, however, there is a truly loud crack: That is rock breaking loose as Rip’s Rock is being shaped by the ice.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”