Coming out of a shell

On the Rocks – The Woodstock Times

Nov. 19, 1999

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder and who can exactly define such a thing as that? Do female porcupines look beautiful to males? The same for female Aardvarks or Armadillos. We hope so, but none of them look beautiful to us. Even if it should be wholly subjective matter, we think that there just are some creatures that are beautiful while others are ugly. The swan would be on most people’s list of beautiful. So too the thoroughbred horse. We think that most people would regard the Walrus as ugly. There’s no offence intended here, after all, animals cannot be offended, or complimented for that matter; they don’t care. In the struggle for existence, it doesn’t often matter how pretty a creature is. And, in Nature, the struggle for existence is what counts.

Nevertheless, we would like to talk of beauty in the animal kingdom today. And we are not thinking of soft furry animals. The invertebrates include more than their share of ugly animals, creepy crawlers that repel us. But there is also beauty among these cold-blooded, dim-witted creatures, and that can be the case even hundreds of millions of years after death.

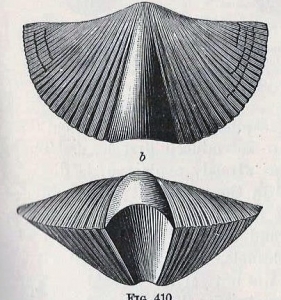

We are thinking about a fossil shellfish named Mucrospirifer, a member of a group called the brachiopods. A brachiopod, like a clam, has two shells, or valves. But brachiopods are not clams; their anatomy does not even place them among the mollusks. Their shells are entirely different. Among the clams, symmetry planes pass between the valves, in the brachiopods, symmetry is down the middle of each one. In lifestyles however, the clams and brachiopods do have much in common. Both lie on the sea floor and draw sea water into their interiors. Both filter the water and find microscopic bits and pieces of food in it. But both have complex and differing filtering mechanisms. All this is important, it tells us that the two groups evolved separately.

Having different evolutionary histories, it is not odd how different their geological histories have been. Brachiopods were among the dominant seafloor dwellers up until the end of the Permian time period, about a quarter of a billion years ago. They nearly disappeared in the great worldwide extinction that occurred at the end of the Permian. Clams had been around as long as the brachiopods, but they have flourished since that awful extinction. The brachiopods have survived but are just barely limping along.

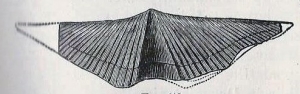

The brachiopods were at their peak during the middle Devonian when Woodstock was at the bottom of something called the Hamilton Sea. And Mucrospirifer was one of the most abundant inhabitants of Woodstock at that time. Mucrospirifer is a genus name and there were many species within this genus. All are attractive but some were of a truly beautiful form. The ones we are illustrating are among our personnel favorites. They have long delicate and graceful left and right points and fine sculpturing. This morphology adapted them for life on a quiet and muddy-bottomed sea floor. Their lives were simple; they just opened their valves when they were hungry and filtered sea water. When not hungry, or if they were disturbed, they would close their shells and remain protected within them. Not very exciting but that doesn’t matter. Believe us, brachiopods are never bored. we doubt that they even know that they are alive.

Mucrospirifer was a big success during the Devonian and for that long time it flourished in abundance. Eventually its success faded and it numbers diminished. Sometime and somewhere, there was a last Mucrospirifer. We don’t know where or when. When it died the group was extinct. It’s sad, but that is the fate of all species including, someday, our own.

But even in extinction, they are still beautiful creatures, and they deserve to be remembered. We always enjoy finding a good specimen. You can look for them in some of the fine-grained sandstones and shales of the Hudson Valley. Try the strata along John Carle Road which is off of the eastern end of the Glasco Pike. Better still, journey up to the Greenville vicinity. The stone walls west of that town yield many of them. If you do go hunting, please limit yourself to just one good specimen and leave the rest for others to see. After all, the form has already gone extinct once.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”