Some fine boulders in Cooperstown 10-31-19

On the waterfront

The Cooperstown Geologist

Feb. 2007

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

When you are a geologist you have to get used to the idea that you are always (pardon this!) a stone’s throw away from a journey into the distant past. We had such an experience recently at Lakefront Park in Cooperstown. There, at the end of the Pioneer Street, are eight sizable boulders. We imagine they are there to keep people from driving into the lake. But they helped us to “drive” into the early Devonian time period. That’s a journey back in time of about 400 million years.

These boulders aren’t from the area; they were quarried somewhere else, but we recognized them immediately. They are from something that geologists call the Helderberg Limestone. They may well be from the Helderberg Mountains near Albany.

Limestones are special rocks for geologists. They carry us off to tropical places, and we mean that quite literally. The material of limestone is called calcium carbonate, stuff that mostly forms in shallow tropical seas. Have you walked the pink sandy beaches of Florida or the Bahamas? Then you have walked on carbonates. Petrify one of those beaches and, presto: sediment becomes rock, and the rock is limestone.

These boulders, however, did not form on some ancient beach. If you get a chance, take a good look at them. They are stratified, that is to say that the rock is layered. Each horizon represents a Devonian sea floor. We found some sandy sea floors and some muddy ones too. This was a mixed marine ecology.

There were plenty of creatures living on these sea bottoms. The boulders are all fossiliferous; look them over, and it won’t take very long for you to find some of these fossils. A visit here is a very colorful journey to the bottom of the sea.

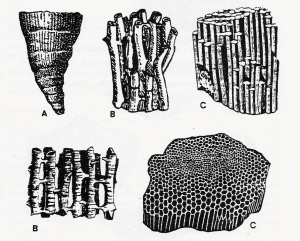

It was the corals that most caught our eyes. Yes, we said corals, and right here in upstate New York! Take a look at the fifth boulder from the right (east) side, especially on the right side of the rock, about two feet from it’s top. Our field notes tell us that there are two types of corals to be seen here. The first is called the honeycomb coral (C on second illustration) and that’s a good choice in terms. It looks like petrified bee’s wax. The second is the horn coral (A on second illustration). It’s called that because it looks like a cow’s horn, wide and round at the top and tapering to a point. You will see something that looks like the cross section of a cut orange. Horn corals have compartments that remind me of the segments of an orange.

There are enough corals here so that we have to wonder if these rocks did not come from a reef ecology. That could be, as the Devonian was a time of many large reefs and there are many Helderberg coral reefs known in New York State.

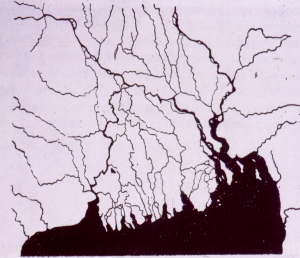

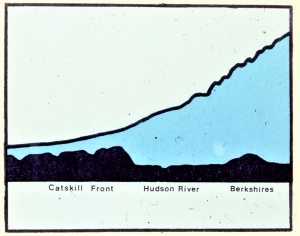

The story gets better when you learn more about Helderberg stratigraphy. As we said earlier, these limestones are exposed in the Helderberg Mountains. But the limestone strata are known to plunge underground as you head west towards Cooperstown. That means that some of the Helderberg lies buried deep beneath Cooperstown. Hundreds of feet beneath Lakefront Park is a great thickness of Helderberg Limestone and a good bit of it is probably fossil reef.

That means (and this is astonishing) that Cooperstown was certainly once the site of a beautiful shallow Bahamas-like tropical sea. Look around you and imagine the pink sands and green seaweeds that were once right here. Look up and see aqua colored waters above you. Imagine the primitive fish that once swam here.

And it only gets better, the more you think about it. Cooperstown is also very likely to have been the site of a Devonian coral reef. This is a pretty area, especially in the autumn, but have you ever, in your wildest imagination, envisioned coral reefs and all their beauty . . . right here?

Geology changes your perspective on things, doesn’t it?

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”