The Old Mountain Turnpike

The Greenville Press

Sep. 4, 2007

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

One of our region’s most historic roads is also one of its least known. It’s the Old Mountain Turnpike. Long ago, the road was the gateway to the Catskills. As far back as the 1820’s guests of the famed Catskill Mountain House Hotel rode carriages up the road to get to the hotel. As the Mountain House prospered, so did the road. When the hotel got too successful it built the Otis Elevated Railway right up the Catskill Front and the turnpike fell into disuse. Today the old road is just a horse and hiking trail, but it still has much of its 19th Century atmosphere. It makes a nice walk in the woods and, of course, along the way there are many rocks.

To get to the old turnpike take Rte. 32 south to the turn at Game Farm Road. Soon you must turn left onto Boggart Road and head south to a right on Mountain Turnpike Road. The trail head is at the end of the road. You can hike all the way up to North Lake State Park if you like, or any part of the trip.

You don’t have to go far before you are in the thick of the geology. The road makes a bend to the right and alongside is an outcropping of red rock. The rocks are floodplain deposits of the Devonian age Catskill Delta. Red strata are old flood deposits, silts and clays deposited by very long-ago floods and hardened into red shale. The darker deposits are the old muds of back swamps. Away from the river channels swamps formed in low-lying areas and dark muds accumulated. Watch for fossil plant fragments in all of this.

As you continue up the road you will encounter, at frequent intervals, a number of sandstone ledges. These are first seen in the slopes above the road, and, as the road rises, the ledges descend to its level. The sandstones are old river channel deposits. They are composed mostly of sandy strata that dip one way or another. These are called cross beds and they are the product of river currents. The currents drove masses of sand into large “dunes” which migrated downstream. Most of those cross beds dip to the northwest as that was the direction that the rivers flowed. In between the sandstone ledges the road tends to be pink or red. These are hidden floodplain deposits. The pattern is clear: River sands are followed by red floodplain shales and then more river sands and so on. The Catskill Front is made up of sandstone and shale “stories” of stone, like a great, tall building. When we make such a hike, we almost always count the stories.

The second story had some prominent ripple marks in a layer of red shale that crossed the road. This recorded Devonian breezes that blew across a shallow floodplain pond and generated currents that, in turn, created the ripples. Those ripples were a recording of a breeze of about 375 million years ago. It is incredible to think of.

At the fourth story we found a vertical ledge of sandstone that had been scoured and striated by a passing glacier. This event had occurred a mere 14,000 years ago, a twinkling of time compared to the age of the rocks themselves.

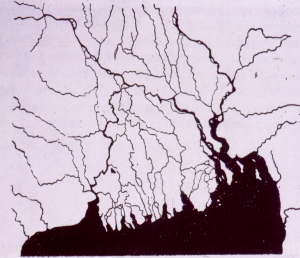

The 14th story was particularly massive sandstone. This must have been a very large river. These rivers were what are called distributaries. In a large delta complex the trunk stream breaks up into many such distributaries. Each one flows into the ocean. Look at a map of the Mississippi Delta and you will see good examples of distributaries. Better still, look at a map of the Ganges River Delta of Bangladesh and you will see a better example.

The road ascended into a hollow and made a sharp bend. Here had once stood the Rip Van Winkle House; it had been the halfway stop for carriages headed up to the hotel. The hollow was naturally air conditioned with cool heavy mountain breezes descending through it. It must have been a nice place to stop.

Just ahead was one of the largest, thickest stories of the hike. We thought that this must have been one of the greatest rivers of the Catskill Delta. These distributaries meander back and forth across a delta plain. A river that is here today, may be gone tomorrow, replaced by a floodplain. That’s why these rivers sandstones alternate with red floodplain shales. The geology here is actually very easy; the sandstones are river deposits and all the rest is floodplain. Everything is Devonian and none of it is less the 350 million years old.

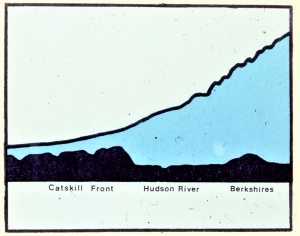

The 24th story brought us to a great overlook. The trees have been cleared away here and a picnic table set up. We interrupted our journey and sat and gazed out at the Hudson Valley. We had seen a lot of geological history already. We had watched as 24 times rivers had crossed this location back in the days of the Catskill Delta. Much of this had been sandstone and sandstone is made of sand. But where had all that sand come from? The only place such large amounts of sand can come from is the erosion of a great mountain range. From our picnic table seat, we gazed across the Hudson Valley and saw the profile of a great mountain range rising above the Berkshires. These were the Devonian age Acadian Mountains. They may once have rivaled the Himalayas, but now they have been eroded away. All that is left are those picturesque hills of western New England. Now we really had seen a lot of history, but there was so much more.

The old trail and we continued up the mountain in a zigzagging pattern. Sometimes the way was very steep, and we thought of how the horses must have struggled here in the 19th century. The sandstones came to be much thicker and prominent. Very large ledges lay left and right of the old path. The road cut right through some of them in several locations. Now we understood what they represented. These sandstones were a record of the destruction of the Acadians. As the old mountains came to be weathered and eroded, they shed their sands into New York State and made the sediments that would eventually become the Catskills. And the Old Mountain Turnpike was a history of all this.

Close to the top of the Catskill Front the old highway levels out. The horses must have been relieved, they had had a very hard haul up the mountain and now they had a little rest. But there was one more sharp turn. In the 19th century, that turn had brought travelers to within a short distance of the Catskill Mountain House hotel, but then it took them away. The highway had to climb one more great ledge and it zigzagged in order to manage that. That last ledge is the thick one that makes up the crest of the Catskill Front. It is the grand ledge that the old hotel stood on itself.

When we finally reached the top, we visited the hotel site and sat and gazed into the Hudson Valley. It had been quite a hike and we had passed through a lot of history. Before us was that ghost image of the old Acadian Mountains. As we pondered it all we realized that there was some pretty strange geology here. We were sitting upon the sandstones of the Catskills that, themselves, were made of sands from the Acadians. The death of one mountain range had given birth to another. Nature does wondrous things.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.’