End of a Limestone Sea July Geological Rumblings in Greene County The Devonian, Part Five 7-25-2019

End of a Limestone Sea July Geological Rumblings in Greene County The Devonian, Part Five Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus Greenville Press September 7, 2005

We have, in the first four chapters of this opus, encountered a very different Greene County from the one that we are familiar with. We have been visiting outcrops of the Helderberg Limestone and envisioning the tropical, shallow water sea that once covered all of our county. We have seen a sea that can be likened to the Bahamas of today. That’s a remarkable concept to ponder, but that is what the rocks tell us.

Obviously, such a tropical sea did not last. This ecology would disappear and be replaced by something new. It is in the stratigraphy that we pick up in this chapter. Find your way to Rte. 23A and travel to a site exactly three tenths of a mile east of the New York State Thruway. There you will find a large dark outcropping on the south side of the road and a much smaller gray outcrop on the north. There is a lot of history here.

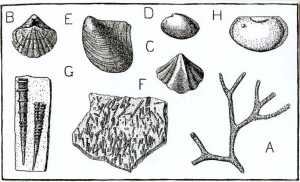

If you look this site over carefully you will realize that, before being largely eroded away, the dark strata passed horizontally over the gray beds; they used to extend across the highway, but they have been eroded away on the north side. That makes them the younger strata. We geologists always start at the bottom so let’s take a look at the older gray rocks. The gray strata represent the top of the Helderberg Limestone. That’s the unit we have been looking at in recent columns. Now, at last, we have reached the end of Helderberg deposition. These limestone strata represent something of an end of an era. If you poke about on this outcrop you will probably be lucky enough to see some fossils here. There aren’t many so please be patient. These creatures were the fortunate inhabitants of a very nice ecology. For millions of years our beautiful shallow tropical seas have been accumulating these limestone sediments and turning them into rock. But now, that time is over. Those overlying dark rocks represent a dramatic, even profound, change for all of Greene County. This was an important moment of history so I hope you can appreciate it.

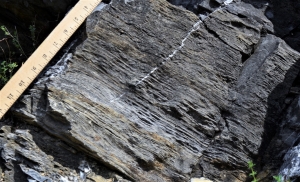

Walk across the street and take a look at the thick sequence of dark beds exposed there. The lower levels are massive ledges of dark strata. The rock type is an unusual one and we were very surprised to find it here. These strata are composed of chert. You likely know chert by one of its other names: flint; it’s a form of silica. Bedded flint is more common east of the Hudson River; it is rare on our western side. The overlying strata, all the way to the top of the outcrop, are black shales. Or at least these beds were black shale originally. These strata have probably been baked a little during Appalachian mountain building events.

These flinty chert and dark shale beds make up a unit of rock called the Esopus Formation. As you can see, it certainly stands out in sharp contrast to the Helderberg Limestone. You can quickly deduce that the environment of deposition must be equally different; this was no tropical shallow sea.

Geologists usually interpret bedded chert as having formed at the bottom of very deep seas. If that is the case here then you are looking at sedimentary rocks which formed at the bottom of an ocean that was, perhaps, thousands of feet deep. We don’t know if this ocean was quite that deep, but this was no puddle. This was a quiet seafloor with very few currents. It was likely that it was very still and that there was very little oxygen in the water. That would have made this a lifeless seafloor.

The overlying black shale accumulated as black mud in waters that were probably a good bit less deep. There may have been some currents, but we suspect that there was very little oxygen. This too is likely to have been a lifeless seafloor.

The Esopus Formation speaks to us of major crustal events. It would seem that the bottom dropped out (literally) of that shallow tropical Helderberg Sea. The crust sagged abruptly, and soon deep, quiet water conditions prevailed. The rich marine sea life and the complex ecologies of the Helderberg Limestone disappeared entirely. A monotonously dark, deep, cold abyss replaced them.

There is more to the story, but you will have to drive a little in order to see it. Find your way to Rte. 23 and then drive a short distance west of the Catskill Creek Bridge. There are outcroppings on the north side of the road. If you look around you will see more of the Esopus Formation here. You will find somewhat baked black shale. The strata here have not only been baked but they have been folded as well. You will see a great round fold in the rock. In the past, this location has been referred to as the “Wheel Cliff”.

On the west (left) side of the outcrop we found some strata that have escaped being baked. Here we could find an original delicate lamination in the strata. These thin beds record long episodes of very slow deposition. A quiet seafloor only slowly accumulates very fined grained, muddy sediment and it does it very slowly. You are looking at a lot of time.

We learned more on the south side of Rte. 23 at the eastern end of the outcrop. There we found another unit of rock. Geologists call this one the Carlisle Center Formation. It is lighter colored, thick-bedded and made up of a little bit courser sediment. The shale has been succeeded by siltstones. This unit completes a sequence which may have a lot to tell us about Devonian history.

Those Esopus chert beds appear to have been deposited in very deep and very still water. They grade upwards into shale strata which seem to represent somewhat more shallow waters. Now there was little in the way of current activity, but conditions were not as stagnant as had been the case. The Carlisle Center siltstones complete the story. These light-colored rocks have much less organic matter in them. Black organics decay in the presence of oxygen which, in turn, is related to currents. The Carlisle seems to have formed in the shallowest waters, in depths which allowed winds to generate currents. This whole sequence of strata can be called a “shallowing upwards cycle”. The great downwarping that initiated this sequence was followed by a prolonged slow shallowing. A lot of that shallowing may have been caused by the sediments that slowly filled in the basin. Pour enough silt and clay into a deep sea and it must become shallow. As it becomes less deep, currents will begin to affect the seafloor. It’s a nice pattern.

But where did the sediment come from? There may be a couple of hundred feet of clay and silt involved. What made it? That, in fact, is the crucial question and answering it tells us the most about what was going on. Geologists look east and back through time to answer that question. Back in the Devonian all of New England was rising in a great, in fact very great, mountain building event called the Acadian Orogeny. What we might call Europe today had collided with old North America just as India has collided with today’s Asia. India’s collision created the enormous Himalayan Mountains, Europe’s collision created the Acadians. Look east from Rte. 23 and imagine the towering mountain range that once was there. It would reach elevations that made it the rival of the Himalayas.

But not during Esopus times. By then the Acadians had just begun their uplift. Small mountains produce small amounts of sediment and most of that is in the form of silt and clay. Our Esopus/Carlisle sequence might look big and thick to us, but it is relatively small by mountain building standards. Still, the infant Acadians had accomplished a lot. They had destroyed that beautiful limestone sea of the Helderberg. They had replaced the limestones with chert and shale, and they had forever left a mark on Greene County. But that was just the beginning. 25, 2019

Living crinoid

Living crinoid