Sam’s Point Sep, 27, 2018

Glaciers at Sam’s Point

On the rocks

Robert and Johanna Titus

Woodstock Times

Sept. 19, 2013

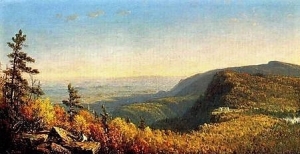

The Shawangunk Mountains are certainly one of the most scenic locations in our region, and uniquely so. The Ridge of resistant quartz sandstone towers above the Hudson Valley and offers numerous views of that landscape. One of the most popular locations is Sam’s Point Preserve, near Ellenville on the south end of the mountains. It is a sizable nature preserve with 4,600 acres of land, most of it perched at the top of the mountains at elevations well above 2,000 feet. It’s owned by the Open Space Institute and managed by the Nature Conservancy.

Today this area is valued as a scenic preserve but, in the past, there were commercial uses. The mountaintop here has abundant blueberries and it used to be that people were hired every summer to come here and pick them. Then, in addition, there were several resort hotels; it was, after all an ideal vacation destination.

But we came here to learn about the geology. How had the area’s geological history given rise to this scenic wonder? We came early on a Saturday so that there would still be spaces in the parking lot. We toured the museum, but not for long; our hearts were in climbing atop the mountain. We headed up the trail.

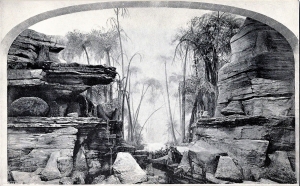

It didn’t take long to figure out why the Shawangunks are there. All along the trail were massive outcrops of quartz sandstone and conglomerate. Quartz is very resistant to weathering and a mountain made out of quartz sandstone will stand out as all other bedrock around it erodes away. The “Gunks” are Silurian in age; that makes them perhaps 420 million years old. Way back then there must have been some sort of coastal plain composed of quartz sand. That would have been similar to our eastern North American coastal plain of modern times. The conglomerates are composed of quartz sand mixed with quartz pebbles. If anything, they are an even more resistant form of rock.

We got up to Sam’s Point itself and soon learned much more about the geological history that went into creating the mountains we see today. We arrived at the easternmost of two platforms, composed of bedrock and seemingly designed for sight-seeing. Naturally, we were more interested in looking down at the rock than gazing at the scenic views. It was, of course, more quartz sandstone, but there was something special that caught our eyes.

There was a polished sheen to the surface of the rock and there were faint striations cut into that surface. We quickly recognized these to be ice age features, common ones at that. Sam’s Point had a long ice age history. Probably going back to the time when glaciers first came down the Hudson Valley, and lasting until the last glacier melted, this site had ice flowing across it. The ice was dirty, carrying a great deal of sand along with it, mostly concentrated at its base. The sand, probably mixed with a lot of silt and clay, actually did polish the bedrock. It sanded it down and planed it off. The generations of people who passed before us had, with their footsteps, worn this down until it was not all that easy to see, but it was there to the trained eyes.

There was more. The glaciers carried with it a large number of cobbles and boulders. As these were dragged across the surface, they gouged scratches into the bedrock. We call these glacial striations. We have seen surfaces like this many, many times so it was hardly a great revelation, but it did speak clearly to us of the fact that there had been a sizable glacier here once. Then we saw more.

We looked up and there was the cliff that defines Sam’s Point. It is another natural platform of quartz sandstone but this one is bounded by a vertical cliff, a big one. Most people would enjoy it as a fine scenic overlook, but our eyes saw back into the ice age. Geologists call this sort of thing a scour and pluck topography. These are common and they are the products of the advance of a glacier. The Hudson Valley glacier advanced from the north and, as it crossed Sam’s Point, it scoured that platform at the top of the cliff. That’s the scour part. Then, as the ice continued south, it yanked enormous masses of rock loose and carried them off. That left a gaping scar in the mountaintop and that is the cliff of Sam’s Point. That is also the pluck part of this landscape.

The cliff faces a compass direction of south-30 degrees-west. That, presumably, was the direction the glacier was traveling. We looked at the striations beneath us, and we had a compass. They too were oriented south-30-west.

Now we had a nice coherent explanation for the topography of Sam’s Point, a real scientific theory to explain everything we saw there. It’s what scientists call an elegant solution to a problem. Everything in the explanation fits the evidence. We would have been flushed with pride at having made such a marvelous discovery were it not for the fact that, no doubt, thousands of other geologists had preceded us here, and had come to the very same conclusions.

==================================================================

Reach the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their site “The Catskill Geologist” on Facebook.