Some Devonian fossils

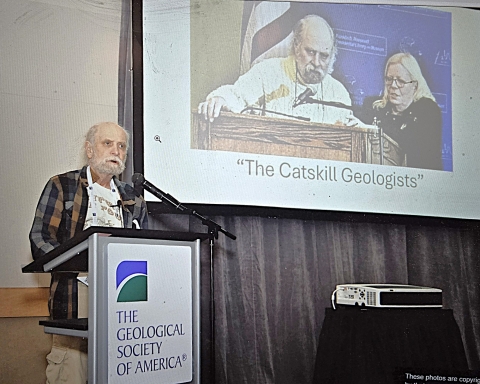

The Catskill Geologists; The Mountain Eagle; Aug 16, 2019

Robert and Johanna Titus

Have you joined our social media page yet? It’s on facebook at “The Catskill Geologist.” We post our upcoming events and publications there. But there is more; our page has over 6,000 members and many of them post things about what they are doing. It can get pretty interesting sometimes and it’s not unusual for us to be inspired to write one of our columns from one of those postings. That’s what happened this week.

One of our members, Stash Rusin, posted a photo of some Devonian marine fossils, that a friend found in the town of Morris, west of the Catskills. The rock is especially rich in fossils. Take a look at our first photo; you might think this is something remarkable, but it’s actually not. We see things like this all the time, but that’s, if anything, what makes it all the more worthy of some discussion. Let’s do just that.

First, there are a lot of fossils in this rock, but almost all of them belong to only one group. They all seem to be creatures that are called brachiopods. These invertebrate shellfish resemble clams. Like clams, brachiopods lived inside two articulating shells. But that is where resemblance ends. “Brachs” are not common today, but some do still live in modern seas. And biologists have found that their internal anatomy is entirely different from what is found in clams. They belong to entirely different forms of life. In short, brachiopods ain’t clams!

Back during the Devonian time period, and this rock is about 380 million years old, brachiopods were the most common forms of marine life. This rock is a petrifaction from one of those Devonian sea floors. But why is there such a dense jumble of brachiopods in this rock? We can never know for sure, but we can hypothesize. We have seen a lot of similar rocks in the Morris region, so we know a good bit about such sea floors. And “jumbles,” like this one, are common.

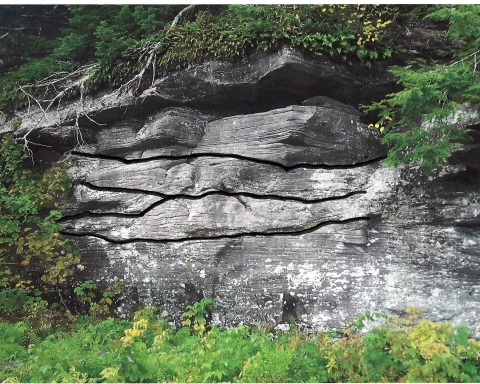

We know that this was a relatively shallow sea. From time to time it must have been wave and current swept. When that happens, the currents pick up and carry away the smaller sedimentary grains. The shells, being heavier, are left behind in increasingly dense accumulations (jumbles). Take a look at our second photo; it shows one of these that we found in Oneonta.

Knowing all this is valuable to a geologist who is interested on deducing what it was like around here all those hundreds of millions of years ago. The more common the shell hashes are then the shallower the water was likely to have been. But, more than that, these transport us through time and let us visit these sea floors.

August 16, 380,765,954 BC — We see a dark, quiet sea bottom — at first. But a storm approaches. The currents pick up quickly. Soon, powerful flows sweep the sea floor. The water becomes brown with dense quantities of silt and clay. Now, a number of shells are uncovered from the eroding sediment. With time, the currents slow down. We look down and see that a dense litter of brachiopod shells has been left lying on that sea bottom. It will, with time, come to be buried by more sediment. That will all harden into rock and wait 380 million years until one of our curious readers encounters it.

Do you have an interesting geological photo? Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”