A Scenic Landscape; mar. 6, 2026

A scenic landscape

The Catskill Geologists; The Mountain Eagle; Dec. 13, 2019

Robert and Johanna Titus

Some landscapes are more picturesque than others. Our Catskills are truly blessed when it comes to scenery. For the two of us, however, it can be the geological past that makes a landscape even more remarkable than you might at first think. You travel south on Rte. 145 from Middleburgh and enter Durham. Watch for Stone Bridge Road on the left and turn onto it. You pass an ancient graveyard with fine old stone tombstones and beyond that is a very nice rolling farmland. Do you enjoy walking through such a cemetery, looking at finely made tombstones? Well. this a place for you. But, for us, it was that farm field that caught our eyes. What’s there? Well, take a good look at our first photo.

114 – Stone Bridge Rd. 12-13-19

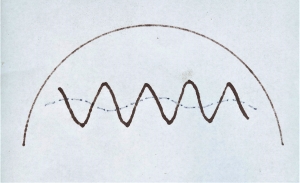

We call this a rolling landscape and that is certainly true. There are so many sinuous curves here; the field gently rolls up and down sort of like the waters of an old Chinese print of a great stormy sea. There is hardly a geologist anywhere who would not look at this without seeing into its ice age past. We would like you to develop this sort of skill, so, we have a little explaining to do. Those sinuous ups and downs have names. The ups are called kames the downs are called kettles. They formed very late in the Ice Age. At that time this landscape was still thawing out. Many locations had large masses of ice buried in the earth here. How large? Well, many were the size of houses. That’ was a lot of ice in each of these. Most are thought to have been buried in earth. That earth acted as insulation and so each mass of ice took a long period of time to thaw out. Some suggest that the melting took centuries. As the thawing continued, a lot of that overlying earth collapsed upon the melting ice. That resulted in those sinuous kettles. The earth in between was left behind as those sinuous kames. There was more; we drove a short distance down Stone Bridge Road and there was a fine small shallow pool of water. See our second photo. That water fills a particularly deep kettle; it is called a kettle pond.

We are experienced geologists and it took but seconds for us to recognize the big picture here. We saw that we were looking at what is called a glacial moraine. That is a heap of earth that was bulldozed into place by an advancing glacier. That glacier advanced as far as it would– so long as the climate was cooling – bulldozing morainal sediments all along its front. Masses of ice came to be incorporated into these earths. Then the climate warmed up and the ice began its retreat. This new landscape began its thawing out. Those blocks of ice took the longest, but they did melt and that produced those kettles. As the kettles formed so too did the kames.

We stood along the road and looked down the valley and then returned to that ice age past. We viewed a still largely frozen landscape. We saw all those kames and kettles. A few of the kettles still had large masses of dirty ice rising out of them. We craned our necks and looked all the way down the valley as far as we could see. There, in the far distance, we saw a great glacier. It rose high above the valley floor and stretched across the entire valley width. Its front was badly fractured and enormous volumes of meltwater were pouring out of each fracture. This was truly a scenic landscape, perhaps more so to us than to others.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”

onian time period, and this rock is about 380 million years old, brachiopods were the most common forms of life. This rock is a petrifaction from one of those Devonian sea floors. But why is there such a dense jumble of brachiopods in this rock? We can never know for sure, but we can hypothesize. We have seen a lot of similar rocks in the Morris region, so we know a good bit about such sea floors. And “jumbles,” like this one, are common.

onian time period, and this rock is about 380 million years old, brachiopods were the most common forms of life. This rock is a petrifaction from one of those Devonian sea floors. But why is there such a dense jumble of brachiopods in this rock? We can never know for sure, but we can hypothesize. We have seen a lot of similar rocks in the Morris region, so we know a good bit about such sea floors. And “jumbles,” like this one, are common.