A Pretty View 5-5-2025

An image of the past – the Schoharie Creek Valley

The Catskills Geologists; The Mountain Eagle

Robert and Johanna Titus; Nov. 10, 2017

We love to drive around in the Catskills. There is always so much scenery to see. Even at 55 miles per hour you can look and see so much, at least the passenger half of our marriage can. But sometimes – no frequently – we feel the need to stop and get out so that we can stand along the side of the road and just gaze – into the past. Let’s do that in this week’s column.

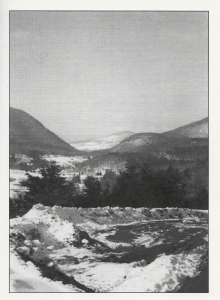

Our journey will take us to the Schoharie Valley, midway between Middleburgh and Schoharie itself. There we find a special sort of imagery. Take a look at our photo. We are looking east from Rte. 30. In the distance is a hill with the unlikely name of “Rundy Cup Mountain.” In the middle foreground is the valley floor of Schoharie Creek. It’s pretty, don’t you think? That valley floor is remarkably flat and that is important, but first let’s concern ourselves with Rundy Cup Mountain. We want you to look again and notice something you might have missed the first time.

There are sharp boundaries between agricultural fields and forests on the slopes of Rundy Cup Mountain. And those sharp boundaries define a nice curvature to the lower slopes of the mountain. There is not a trained geologist in the whole world who would not immediately see what we saw. We looked, and then turned around and looked west; we saw the same curvature on that side of the valley. That curvature defines what we call a U-shaped valley.

And that is the dead giveaway to the valley’s long ago history. A U-shaped valley, like this one, is always the product of a valley glacier. We looked again and, in our mind’s eyes, we gazed into the past and saw the Schoharie Creek Valley filled, almost to the top, with a glacier. Our mind’s eyes rose up into the sky and we looked down on it. We had returned to an episode of time, late in the Ice Age. We looked south, and we saw that glacier, confined by the valley walls, and moving like a river of ice, south through the valley. The white surface of the ice was fractured by great, dark, curved crevasses. These curvatures betrayed a southward motion to the ice.

We, the mind’s eyes, paused a full thousand feet above the ice. It was a warm day, by ice age standards. Meltwater, in abundance, had accumulated beneath the ice, and it was lubricating that southward motion. We hung in the air and listened; we heard creaks, and groans emanating from the moving ice below us. From time to time, great, explosive, cracking, echoing sounds followed. On this day the brittle ice was advancing at the unheard of pace of 100 feet per day!

It had been a clear ice age mid-June morning, but now it was late afternoon. The sun shined down directly on the ice and a thick ground fog had formed. The fog rose up and enveloped us; we could no longer see the glacier. When the fog finally cleared, it was very late in the day, but it was a very different day. We, the mind’s eyes, had traveled centuries through time – the mind’s eyes can do that. We had arrived at a time, long after that valley glacier had melted away. Now, the entire bottom of the Schoharie Creek was filled with a sizable meltwater lake. Its waters stretched out as far as we could see to the north and to the south. Beneath those waters, sediments of silt and clay were accumulating.

Now we were able to put together the whole story of this part of the valley. Those curved valley slopes had been sculpted by the passing ice; the flat valley floor was younger; it dated back to the level bottom of that post glacial lake.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.com. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.” Read their blogs at “thecatskillgeologist.”