The Rosendale Trestle – Feb. 23, 2023

The Rosendale Trestle

On the Rocks, The Woodstock Times; May. 16, 2016

Robert and Johanna Titus

Have you been down to the newly restored trestle at Rosendale? It’s just another one of those really good ideas that turns up from time to time. You have, quite possibly, been on the walkway that crosses the river at Poughkeepsie. That’s the old railroad bridge that was refit for foot traffic. Now it is a grand tourist attraction. That walkway takes you on an almost breathtaking crossing of the Hudson. Well they did pretty much the same thing at Rosendale, just on a much smaller scale. You have to go and see it!

This had once been an active railroad trestle that crossed the Rondout Creek at Rosendale. That was in the late nineteenth century. Rosendale had, back then, been one of our region’s real industrial centers. It manufactured very large amounts of natural or “Rosendale” cement. They must have needed a railroad and they did have one. That railroad connected New Paltz with Kingston. We rather suspect that stops were made to pick up cement. Both the natural cement industry and the railroads are now just long-ago memories. The railroad closed in 1977, but the trestle survived. It towers 150 feet above the Rondout Creek and it is more than 900 feet long. For a brief time it served as a professional bungee jumping site, but that did not last. It needed to be restored so it could be opened up for foot traffic, and that did happen. The new foot traffic trestle is the centerpiece of the 22 mile long Wallkill Valley Rail Trail. It opened in 2013.

We kept meaning to visit the trestle and we kept putting it off, but finally we did go. It was well worth the trip. To get there take State Rte. 213 through Rosendale and head west. You will pass beneath the trestle. Watch for Binnewater Road, turn right and then left into the kiln parking lot. From there you have access to the rail trail that will take you for the short walk to the trestle. That parking lot is worth the trip by itself; there are a large number of old industrial lime kilns that date back to the natural cement days.

Well, we worked our way up the trail and soon found ourselves out on the trestle.

Take a look at our photo to see the view; it is a good one. We, of course, enjoyed the scenery but we were soon dreaming geological thoughts about the landscape before us. Right here, the Rondout Creek passes through something that just falls a little bit short of being a genuine, authentic canyon. The slopes on each side of the river rise quickly and steeply. How did this happen?

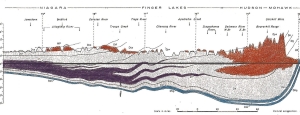

We had some research to do. But, fortunately, we already knew most of the basics; we had worked this area before. We knew that the Rondout Valley has had a rich ice age history. Back in time, late in the Ice Age, there had been one final advance of the ice. A valley glacier, a single large stream of ice, had advanced up the Rondout Valley. We are not sure how far it got, but it must have actually approached Port Jervis. Then the climate warmed and the ice began to melt away. That caused a retreat, actually a melting back of the glacier. For a substantial period of time the remaining ice dammed the valley and that caused the formation of a glacial lake called Lake Wawarsing.

Someday, perhaps you will find yourself driving southwest on Rte. 209. After passing Ellenville, you will begin to see a broad flat valley floor. That’s the bottom of Glacial Lake Wawarsing. You will see that it was a big lake and it all lay upstream from Rosendale. Well, we knew every bit of this when we were standing on the trestle. That knowledge was our passport into the past.

The two of us walked to the east side of the trestle and looked that way. We saw the ice coming toward us. The glacier passed us and continued on to the west. Next we walked to the western side of the trestle. It was about 1,000 years or so, later. The ice, that had clogged the valley in that direction, was in the process of melting away. It might be better described as disintegrating. Climate change was in full force. Vast, enormous volumes of meltwater had been liberated by the warming. And all that water was headed toward us. We were the mind’s eye, the human imagination, and we were standing upon an imaginary trestle at a very real moment in time, an important one.

Raging, foaming, pounding masses of whitewater cascaded by, just beneath us. What an image we saw; this was the very day when more volumes of water would pass by than ever had before or ever would again. This was the very moment in time when the Rosendale canyon was taking shape. What was going on just beneath us was extremely erosive.

Off to the west, Lake Wawarsing was draining at an almost alarming rate. And all of that water was thundering by beneath us. The power of the moment was unsustainable; all bad things must come to an end. The lake was emptying. We watched as the currents abated. We gazed as the water levels ebbed below the trestle. We saw something of a normal flow being restored.

We were absolutely thunderstruck by what we had witnessed. We had long understood this sort of thing, but to actually see it is something altogether different. What a gift it is to be geologists; we get to travel to beautiful places but we get to see them as others do not.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.” Everybody else has.