A Woodstock Ice Age, Part 3: High tide

On The Rocks; The Woodstock Times, 2008

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

There was a time when the very concept of the Hudson Valley did not mean very much, and it was not all that long ago, at least not in the way that geologists think about time. Let’s take a plane ride back 20,000 years ago. We are the mind’s eye, the human imagination, and we can do such things. We are flying from what will someday be Woodstock to what will be Kingston. It is a clear day, and we can see all the way to the horizon in any direction that we care to look. There is virtually nothing to see.

Looking straight down, we see a pool-table flat surface of white. We drop down and fly close to the “ground” (the mind’s eye can do such things) and only a little more detail becomes apparent. Now the whiteness is broken by a few dark fractures. We are close enough to tell that it is ice that we are looking at, and now we can also see some drifts of snow. But, for all practical purposes, this is a featureless and white Arctic landscape.

We rise up high into the sky, higher than before. Off to the east the white extends to the horizon with absolutely no blemish. That horizon shows the Earth’s curvature, but it is a white curve against a very pale blue. We look north and see exactly the same vision. Then we look west and there, at last, is the one blemish to the perfectly white landscape. The peak of Slide Mountain pokes above the ice; it is an island in a sea of ice.

The sight of Slide’s peak is a welcome one, but the view quickly generates a rush of awe. Slide rises to more than 4,000 feet in elevation and only just a little bit of its summit is showing; there must be a very large amount of ice. The conclusion is inescapable: there are thousands of feet of glacier beneath us. We used the word “Arctic” but we might better have called it Antarctic. There is nothing in the modern world to match what we are seeing except the vast whiteness of Antarctica. It is this notion that inspires such awe.

Millennia from this time, scientists will recognize this as one of the great glaciations of all history, and they will name this glacier the Woodfordian Ice Sheet. More than half of the North American continent is, on this day, covered with ice. We are the mind’s eye; we rise up thousands of miles above the surface and gaze to the north. Even this high there is nothing but white curved globe as far as we can see in that direction. Once again, a rush of awe overwhelms us.

To the south we do better. We are now high up enough to see the southernmost extent of the glaciation. The ice has reached into northern New Jersey and northeastern Pennsylvania. More ice has reached as far south as Long Island. Beyond the whiteness is a barren and desolate landscape. Someday scientists will call this bleak region a tundra or a “periglacial” zone.

Now we understand why the very notion of the Hudson Valley is meaningless. All of that valley, along with the Catskill Front, is buried in the thickness of the ice we see. It gets worse: off to the east both the Taconic and the Berkshire ranges are similarly submerged in ice. That is why the horizon to the east is so flat.

We continue our ice age flight back to the north. With our mind’s eye we operate a form of radar that penetrates the ice below. We can see the Hudson Valley below and we can see the Catskill Front and the Catskill Mountains. We are the mind’s eye; we can do such things as this.

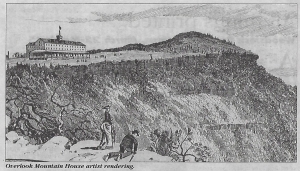

We pick out Overlook Mountain within the ice and we drop down and pass down through hundreds of feet of glacier and arrive at the very peak of the mountain. Again, the mind’s eye can do such wondrous things. We watch as the moving ice is dragged across the knob of rock, found today just north of the fire tower. Boulders and cobbles litter the bottom of the ice, and these are dragged across the bedrock. They scour that surface and also carve very prominent striations into the rock. A polished and scratched surface is soon developed.

Overlook Mountain

Now, for us, the mind’s eyes, time speeds up and we feel the climate warming. We watch, again with awe, as the Woodfordian Ice Sheet begins melting all around us. In what only seems to us as the briefest period of time the peak of Overlook emerges from the ice. Now that knob of rock is left behind; its scratched surface remaining as a testimony to what happened here during the Ice Age.

You can see all this for yourself; go out and climb Overlook.

Reach the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page thecatskillsgeologist.com.