The Glasco Turnpike 1: its Ancient Tropical Sea

On the Rocks; The Woodstock Times, 2008

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

Wherever you might happen to find yourself while reading this, please wave your arm through the air around you and begin to wax philosophical about it. This spot has been here for as long as the Earth has been here and that is about 4.6 billion years. Contemplate the history that has unfolded right here. Think of the plants and animals that occupied the very space where you are now. Geologists are accustomed to being awed by the things they discover and encounter and this is one of those marvels.

This location has a longitude and latitude. Woodstock is at 42 degrees latitude by 74 degrees longitude. If we could go back in time and bring a GPS device, we could find this spot and see what it was like way back when. That notion is mostly beyond the reach of science but just not entirely. We would like to take you back in time to this location and see what it was like at several important moments in time. It is all part of our effort to bring to meaning of the theory of evolution to you, the local readers.

Evolution only works if the world is very old, billions of years, in fact. Our aim over the next five columns is to take a journey through time, curiously our trek will be mostly along the Glasco Turnpike. Let’s head east on the Glasco Turnpike until we arrive at its intersection with Rte. 9. Turn right, which is south, and go a short distance, just a half mile or so. Notice the gray ledges along the east side of the highway. That is our first time-travel destination.

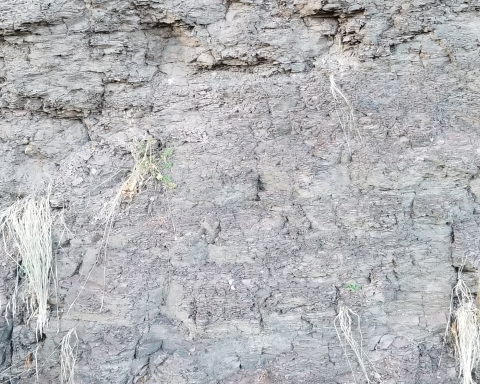

This is the Glenerie Limestone. It is very, very fossiliferous so we geologists are very fond of these rocks; they are always a lot of fun to visit; their time is fun to visit too. As you approach the roadside outcrop, notice the horizontal layering to the rocks. This is, of course, called stratification. The marvelous thing about these horizons is that each was once the bottom of the Glenerie Sea. When you get to the outcrop, put your finger on one of those beds of rock. You are actually touching a seafloor. That’s not exaggeration, it’s not literary license, it’s a fact. The water is gone, and the old sediments have hardened into limestone, but each horizon was once the bottom of a sea.

That was a long time ago; in fact, that’s the whole point of this article. We have now visited the Devonian time period; it is just a little more than 400 million years ago.

Now, take a good look at the various strata. Some are not very exciting, just dull gray rock. But other horizons are enormously fossiliferous. You will quickly find beds of limestone which, upon careful viewing, appear to be all broken shells. Some of these beds are just a complete hash of shells. They have lost their original bright colors, but they are still shells.

These are invertebrates, mostly forms called brachiopods. Like modern clams, they had two shells, but that’s all the similarity that the two groups share. Brachiopods are not mollusks; they belong to a wholly different category of invertebrate. They were very abundant back in the Devonian and made up the dominant form of sea life here.

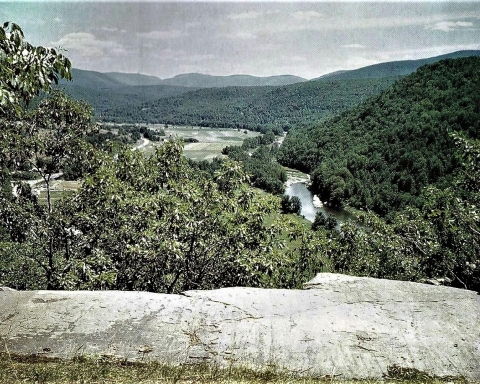

We are the mind’s eye; we have waved our arms through the air, and traveled back into time, all the way to the early Devonian. We find ourselves adrift on the surface of the Helderberg Sea. All around us, in every direction, an empty and endless sea stretches out to the horizon. There is no land to be seen anywhere. The waters are aqua in color, that’s typical of a tropical sea. And that is exactly what the Glenerie Sea is. We feel the water temperature and it is a balmy 82 degrees.

Below us, the sea is so shallow that we can see the bottom. There are active currents and that has swept much of the seafloor clean. We see a lot of pink, very coarse sand drifting and shifting back and forth as waves sweep across the bottom. There are a lot of broken shells down there, most all of them are from brachiopods; they have suffered during common storm events and have come to be broken up into a colorful hash. We look around but do not see and living brachiopods. That’s just bad luck; we picked the wrong moment to visit the Glenerie.

It is an exhilarating experience to travel through time like this. It is such a privilege to see the distant past. But the main point is that this bas been a Darwinian journey to a very ancient world populated by very different creatures from those of today. Such visits are always all too brief. In a blink of the eye, we are back on Rte. 9G. It is winter in Ulster County. The highway is dirty with grit and salt; the outcrop is dirty and drips with icicles.

Next time: the stagnant sea.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”