Monsters in the Closet Dec. 24, 2020

Monsters in the Closet

Stories in Stone -The Columbia County Independent

Feb. 2004

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

We don’t know what it is about this time of the year, but we seem to start finding silverfish around the house, especially in our closets. What attracts them? We don’t know; they are just bugs, who can explain them.

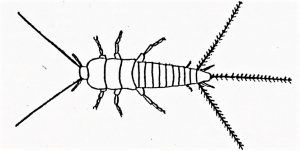

Well, in fact, they are not just bugs. If you have a problem with silverfish do what we did. Stop for a moment and take a good look at them. They are, in fact, something quite special. If you can, get one to slow down long enough to look at carefully, you will see something very interesting. That’s a tough thing to do as they love to scurry around very quickly and don’t like to stop to be looked at. We recommend some bug spray, after all, it is the interest of science (and a bug-free home). Anyway, once you get one to stop moving you will quickly see that they are not like other insects. They do have six legs as all good insects should, but that is about it. Silverfish do not have wings and most insects do have wings. That’s a very primitive trait among insects.

Once you get one to stop moving you can see what they look like. They might remind you of little scorpions, but that is superficial. They have a series of silver-colored scales running the length of their backs, hence the name silverfish. There are two bristly antennae up front and what looks like three more behind. That’s why they are sometimes called bristletails. They do have six legs as do all proper insects., but that’s about it. All in all, you don’t have to know much invertebrate zoology to tell that silverfish are very primitive insects, they just look it, and that’s why they are so special.

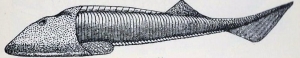

You see, silverfish belong to a very ancient and primitive group of insects. Most insects have wings, four of them in fact, but the silverfish have none at all. Nor do any of their ancestors; the lineage extends back to before insects evolved wings. And when we say extends back, we mean a long, long time. Silverfish date back to the Devonian time period. Around here that’s important as all of our local bedrock is Devonian in age. As luck would have it, most of our sedimentary rocks were deposited in a terrestrial setting, one where insects abounded. This was the Gilboa Forest of the Catskill Delta complex.

The land of Gilboa was, like any great delta, a morass of forests, lakes, ponds, swamps and rivers. It was tropical in climate and it must have been a lush environment, perfect for insects. And it is rich in fossils, including insects, not terribly different from silverfish.

Creatures like silverfish have a special place in the hearts of paleontologists. We call them “living fossils” and that’s a good term. They have evolved so slowly and so very little that they remain virtually unchanged from their ancient ancestors of nearly 400 million years ago.

Living fossils are like keyholes into the past. We can look at them and see creatures as existed in the ancient past. In this case silverfish speak to us of the early ancestry of insects. These are the insects that first lived on the lands of the distant past, long before they evolved an ability to fly, chirp, sting, ruin picnics, and all the other things that modern insects do. We paleontologists love to see living fossils; they give us a firsthand look at the past.

Some people are proud to be able to trace their ancestry back to the Mayflower. That gives their families a 400-year history in America. We guess that is nothing to sneer at, but silverfish can trace their American ancestry back 400 million years. It may be humbling to see in these bugs, and primitive bugs at that, such a blue-blooded heritage.

So why are these monsters of the past so common in our closets. Well, it happens to be that they love eating the starch that is found in paper. We took another look back into our closets and found old copies of the Independent. It would seem that our newspaper is not just food for the mind.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”