What’s the Point?

On the Rocks

The Woodstock Times Oct. 14, 2998

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

To most people the Shawangunk Mountains are best known for the Mohonk Mountain House or for the hang gliders and rock climbers you will see in abundance on sunny summer Sundays. While the Shawangunks may be a lessor mountain range by world standards, they are still very substantial landscape features in the Hudson Valley. They are geologically distinct from the neighboring Catskills and they have their own story to tell. If you are interested, then a good place to begin to learn the story of the “gunk’s” is at Sam’s Point.

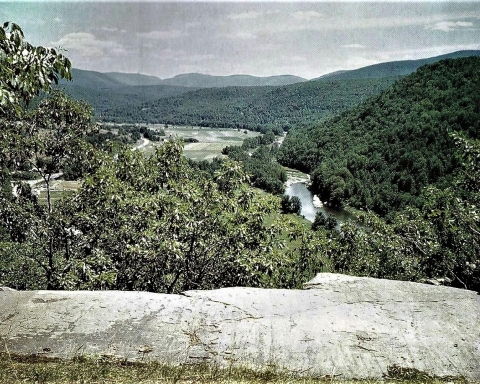

Take Rte. 209 south to Ellenville, then take Rte. 52 east up the west slopes of the Gunks. From there take Cragsmoor Road to Sam’s Point Road and watch for the signs. There is a parking fee. It’s a bit of a trip so allow a whole day. Sam’s Point is the property of the Nature Conservancy. The ice caves are only open seasonally but there are still many open hiking trails with fine views of the Hudson Valley region. The trail to Sam’s Point is a short, easy walk. It takes you along and under a cliff and then up to Sam’s Point itself. If it’s clear you can see all the way to the tower at High Point in New Jersey. To the north you can see most of the rest of the Gunks.

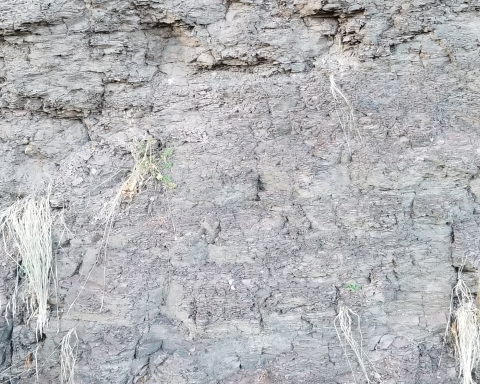

We wondered what the Shawangunks were and why are they were here? The answer began to appear as soon as we saw the rocks of Sam’s Point. They are of a striking lithology, almost all thick-bedded strata of bright white quartz sandstone. The name implies its composition; it’s a nearly pure quartz sand. Even the grains are tightly cemented together by a quartz cement.

Quartz sand grains glued together by quartz cement; that’s a recipe for a very sturdy rock. Quartz sandstone is about as resistant to all of the processes of weathering as any type of rock in the world. No wonder there is a mountain here. There are actually two massive layers of quartz sandstone here, each running about 250 feet thick. They are separated by a horizon of softer, more easily weathered rock. The two have slowly eroded into separate ridges. It adds some variety to the landscape.

As we climbed around and looked at those strata, we found that there was more than just sand here. Much of the volume of the original sediment was a quartz gravel. Technically this is not a sandstone; when gravel is this abundant, the rock is better called a different name: conglomerate. This one is officially named the Shawangunk Conglomerate.

Where did all this sand and gravel come from and how did it get here? The answers to those questions take us back to the Silurian time period, a little more than 400 million years ago. Back then there was a mountain range, known as the Taconic Mountains, located in western New England. Even back then these were old mountains, and they were then in the final stages of dissolution. Weathering and erosion had slowly been wearing them down and grinding them into sediment. With such very old mountains there has been plenty of time for the weathering processes to destroy the softer and weaker minerals. For the most part their grains are entirely dissolved or converted into clay and washed away. What’s left is quartz, that most resistant of minerals.

So that, in a nutshell, is the history of the Gunks. In the past they started out as a deposit of quartz sand and gravel, accumulating on the floor of a shallow sea, adjacent to the crumbling remnants of a once mighty range of mountains. Slowly these sediments came to be cemented into masses of white sandstone and conglomerate. Then they were gradually uplifted into hills and then even more slowly eroded into the morphology we see today, a scenic but lessor range of mountains. But these mountains, like the ones before them, are doomed. Weathering and erosion will cause them to crumble. Someday these grains will be part of a newer quartz sand sediment, located in the Atlantic Ocean. Those sands will start to harden into a new quartz sandstone and the cycle will start all over again.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”