Gaps in our Knowledge

On the Rocks/ The Woodstock Times

Jan. 22, 1998

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

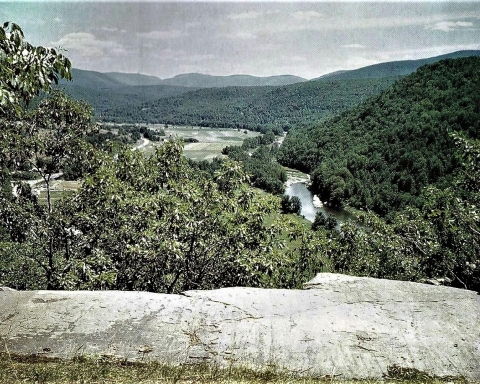

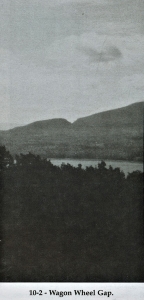

Take Rte. 28 west from Woodstock, turn right at Dancing Rock Road (it’s two miles east of Boiceville) and go up one mile to the end of the paved road. Look south and, there below, is the Ashokan Reservoir. Above it, on the horizon, is High Point Mountain. The mountain profile is nothing particularly unusual except for one feature. There is a notch cut into the top of the mountain. It is the sort of landscape feature that you pay little heed to; it doesn’t seem all that strange until you look at it carefully and ask a simple question. How did it get there?

The notch has a name: it’s Wagon Wheel Gap. we suspect that the name came from the deep ruts that old fashioned wagon wheels carved into roads before the auto age. The gap is at least 200 feet deep and steep on both sides. It seems to be something cut into the mountain. It was. Not surprisingly this odd landscape feature does have a story to tell and it is a surprising one.

Wagon Wheel Gap is a glacial feature, but different from most. Glaciers are very good at eroding landscapes and they can carve notches into the landscape. But that kind of glacial erosion produces a nice, smooth, U-shaped gap. West Kill Valley is a good example. It’s relatively wide and rounded at the bottom. Stony Clove is narrow like Wagon Wheel Notch but it has been cut right down to the level of the valley. Wagon Wheel Gap is altogether different. There’s nothing broad and round about it. It’s a sharp slash, like something cut by a knife. The bottom of the gap lays well above the level of the nearest valley, in fact 700 feet above. Wagon Wheel Gap seems something quickly and violently cut into the High Point mountain.

The story of Wagon Wheel Gap takes us back about 17,000 years. At that time a large glacier was pushing up the Esopus Creek valley. It passed the present site of the Ashokan Reservoir and pushed on; we are not sure how much farther. This ice did reach a still-stand and then, with warming climate, it began a slow retreat. The warming halted briefly, and the glacier reached another still-stand, just exactly abutting against the present-day gap.

The ice acted as a dam and so it blocked the whole upper Esopus Creek which then filled with a reservoir of cold water. The water had to drain off somewhere and it made its way across the slopes of High Point and drained off to the south. In what had to be a very short period of time, that flow of water cut into the mountain and carved the gap we see today. It’s quite something to imagine. There would have been an enormous amount of water pouring through the gap back then. There would have been all of the normal flow of the Esopus Creek plus all the water provided by the region’s melting glaciers. That’s a lot.

The flow must have positively raged through the Wagon Wheel, perhaps the mother of all whitewater flows. And loud too, a thunderous, pounding cacophony. It must have torn into the mountain with an effect something akin to a buzz saw. At any rate, the flow must have continued while the Esopus glacier retreated down the valley. Eventually the flow of water must have found other ways out of the valley and Wagon Wheel Gap would have been very abruptly abandoned. The whitewater flow would have dried up overnight.

And there it lies today, an abandoned notch, lying there silently in the mountain. It’s a landscape oddity with a colorful past. But how many people know even to notice such a thing. It’s, to most, just a notch in the mountain, nothing of note. What a marvel it is that glacial geologists can come along and understand these things.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”