Honk of You love Reefers

ON THE ROCKS – The Woodstock Times

May 21, 1998

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

We geologists owe a great deal to the highway departments. It is necessary for them to cut great slashes into the hills and mountains so as to allow the passage of roads. And thus it has been that they have, especially since the 1950’s, been providing us with thousands of beautiful exposures of bedrock. Many of these are quite impressive – great, towering cliffs of rock, rising above the passing traffic. They are like magnets to geologists, they lure us to stop and explore.

Rte. 209, south of the Saw Kill, displays one of the area’s better exposures. It’s a very impressive cliff of black stratified rock. The beds of rock here are called the Mt. Marion Formation. That’s one of the area’s more important units of rock. It’s a big, thick sequence of sandstone and shales; the beds piled up to a thickness of about 500 feet. Not surprisingly, these are the layers of rock that make up Mt. Marion itself.

The sedimentary rocks of the Mt. Marion Formation record a distant moment in the history of this region. They were deposited as black muds and dark sands at the bottom of the relatively deep ocean that once existed throughout all of eastern New York State. But that was about 380 million years ago.

As we said, these exposures are irresistible magnets for all geologists, and we are no exceptions. We drove down Rte. 32 and turned onto the Rte. 209 ramp and took a nice slow drive along the great exposure. It was well worth the effort; our luck was very good.

Practically the very first thing that we noticed was a fine specimen of a fossil coral. That was a big surprise, as we had never imagined that this would be a place to search for corals. We usually find fossil corals in limestones. Limestones record ancient shallow, tropical seas, places ideal for corals to grow and flourish. In such locations, corals grow into the great colonies that we know as coral reefs. Each reef is composed of thousands of individuals living together in a single colonial skeleton. But as we looked up at the strata of the Mt. Marion Formation, we could not imagine such an image for this unit of rock.

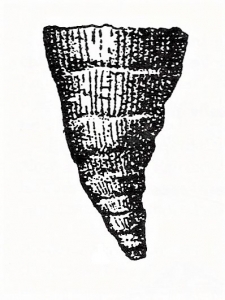

Black shales and sandstones are different from limestones. They accumulated on murky, dark sea floors, places not usually well-suited for corals. But the corals we found here were not the regular run of the mill forms; these ones are known as horn corals. Horn corals are, as the name implies, uncanny duplicates of the horns of cattle. They are widest at the top and taper downwards to a point. The specimens we had collected are probably called by the Latin name Cyathophyllum. They would have been pretty well-adapted to life on the dark, muddy sea floor. We suspect that they grew upwards so that their sharp pointed bottoms stuck into the mud like golf tees. Their wide openings would have projected above the sea floor and they would have avoided being clogged with mud.

Corals are predators of sorts; obviously they do not stalk their prey. Instead they are known as “awaiters;” they lay upon the sea floor and wait for some unwary prey to come by. They have tentacles that capture their prey and pull these victims into their gullets for digestion. That’s not a very exciting life, but it works well; corals have been around for about half a billion years and they are likely to be around for another similar length of time.

And, so it was, as we drove along the black shales of Rte. 209, that we imagined ourselves at the bottom of an ancient sea. All around us, on a dark muddy bottom, lay numbers of horn corals with their light colored, fleshy tentacles waving back and forth at the surrounding waters, each one grasping greedily in hopes of food. There is certainly a great difference between the world as it is, and the world recorded in the strata.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.com. Join their facebook page ‘The Catskill Geologist.”