The Worm Turns

On the Rocks – The Woodstock Times

June 26, 1997

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

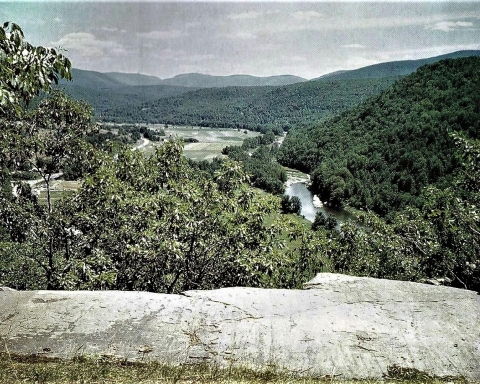

On Rt. 9W, at Glenerie, the Esopus River descends two ledges of rock known as the Glenerie Limestone. These ledges make up what are either high rapids or low waterfalls, depending on your point of view. In any case they also make a very nice setting and the shores of the Esopus there attract a lot of people. We sat on the banks for a while and watched people go by. There were two fishermen, who had no luck. A couple walked by with their dogs. Several young boys came by on their bicycles. One elderly man wandered along the shore, we think just for the pleasure of it.

Such is life for human beings who are not at work, but just intent upon enjoying a little leisure. The Glenerie Falls provides a setting to idle away a few minutes or a few hours. As I sat along the Esopus, we was watching just a few random moments in the history of life. Nothing special occurred, nothing historic or even meriting the slightest of note. Most of what goes on in this world is like that. Little that happens is really of very much significance. Such is life.

It’s easy to forget that this spot has always been here. The world is four and one half billion years old and this precise longitude and latitude has been here all that time. What was it like here a century ago? We don’t know, but with the help of a historian we could easily guess. How about 500 years ago? A little harder, but good guesses might come from an Indian archeologist. How about a million? or a hundred million? or a billion years ago? Even a geologist has a hard time answering those questions.

So much of earth history slips off into the past without leaving any monument or even a clue as to what had transpired. But none of these moments is likely to have amounted to much, just simple events during average times. Countless living creatures have passed by the Glenerie Falls site and almost all are gone and have been entirely forgotten by history. Disappearing into the oblivion of the past is a sad fate that we all share eventually. . . almost all.

But sometimes, hundreds of millions of years after their deaths, signs of the lives of ancient creatures return to light. And we mean that very literally. Memories of ancient organisms are often revived when weathering and erosion of bedrock brings to surface the evidence of lives long lost. We geologists call these “trace fossils.” They are not the bones or shells of ancient organisms, but the evidences of ancient activity, the very behaviors of the past. The best known trace fossils are dinosaur footprints. People have marveled at them for more than a century. They forget that these “marvels” are only evidence of the most every day and literally pedestrian moments in the lives of dinosaurs. Unfortunately we don’t have dinosaurs or their footprints anywhere near Woodstock. But we do have other trace fossils.

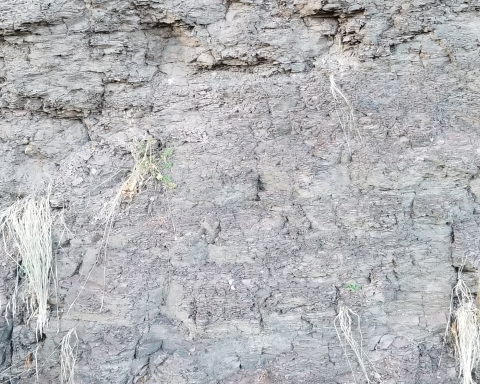

A lower ledge of the Glenerie Limestone forms the lower cataract of the falls. The rock is tough and brittle stuff and it has held up well against the elements. On the bank, just below Rt. 9W, this ledge has been brought to the surface by folding of the bedrock. The upper surface of the inclined stratum is a fossil wonder. It’s densely littered with the trace fossils of worms that lived here about 400 million years ago.

The animal has a name – it’s Zoophycos. It was a common marine worm, much like many that live today. You probably know that earthworms make their living by burrowing through soil, consuming and digesting it as they slowly move forward. Similarly, Zoophycos burrowed and ate its way through the marine sediments, including the limestone sediments of the Glenerie. Zoophycos was extremely meticulous in the way it dined on sediment. It burrowed forward for a while, its path taking it in a broad, round loop. The worm then turned abruptly and returned, closely paralleling its first path. Then, once again, it turned on a dime and paralleled its second path. Back and forth it continued, carefully consuming all of the sediment. Eventually the back and forth path took on the form of a rooster tail and that is the common name it goes by. “Rooster tails” are common throughout the marine sandstones and shales of the Catskills, but this is the first time we have seen them in a limestone. They are fascinating fossils and marvelous insights into the details of ancient life, but they record such mundane moments: Worms eating mud!

If you carefully examine this ledge of rock you will be surprised at how densely burrowed it is. A large population of these worms must have lived here. To survive on a limited food resource, they had to evolve the careful feeding patterns that we see. We doubt they missed anything. There is, we suspect, a message here.++