Rocks with sole July 26, 2018

Rocks with Sole

The Woodstock Times

A long time ago

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

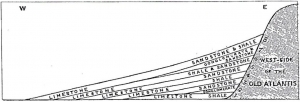

The Austin Glen Formation is not all that impressive a rock to look at. It’s made up of alternating strata of gray sandstone and black shale. But in many ways, it is one of the most awe-inspiring rock units in the area. It makes up much of the bedrock on the east side of the Hudson River. Travel across the Kingston-Rhinebeck Bridge and it makes up the first outcroppings of rock you will see. These are the low cliffs on either side of Rt. 199. We made the trip recently and took a good look at these outcrops. About 30 paces east of the beginning of the west-bound lane’s exposure we found a remarkable sedimentary structure: One overhanging stratum of rock displayed a crenulated surface. We recognized the form as a type of “sole mark” and it conjured up quite an image from the past.

The sands and muds of the Austin Glen were deposited in some of the deepest waters that make up ocean basins. There is a wonderful word, “abyss,” used to describe great depths in the sea. The abyssal plain is a great vast flat sea floor, about two miles down. But we are talking about something even deeper. We are speaking of a sea floor zone called the hadal zone, that’s a great deep trench at the bottom of the sea and it can be several tens of thousands of feet deep. Today’s Marianas Trench is the best such example we can go see. It is 36,000 feet deep, an incredible depth. We don’t think that the Austin Glen was quite that deep, but who knows for sure.

Not only is a marine trench of this sort deep, but it is also very steep-sloped and that gets us to today’s story. You see, the shales of the Austin Glen formed originally as black muds. It’s typical for such great depths to accumulate muds; the fine clay particles settle to the deep-sea floor and make up the muds. But the sands are different; sands are usually shallow water deposits. Obviously, the sandstones of the Austin Glen weren’t shallow water deposits so how did they get there?

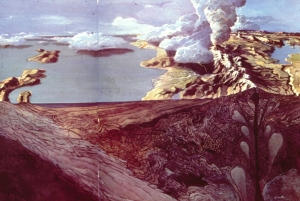

The answer it that the sands were once part of something called turbidity currents. These are very fast-moving currents of dirty (turbid) water that rushed downslope at speeds of up to 50 mph. More likely than not, an ancient earthquake struck and displaced a large amount of shallow water, sandy sediment. Billowing masses were thrown up into suspension by the quake and then they began to flow downhill under the influence of gravity, soon accelerating to their rapid pace. A turbidity current is one of those very powerful forces of nature. Fortunately, there are few animals that stand in the way and few deaths result. There is some destruction, but only in the form of rapid erosion of sediments crossed by the current.

At the bottom of the slope the turbidity currents slow down but, still moving rapidly, they spread out across the soft muds and deposits their sandy sediments. The sudden deposition of sandy sediment upon soft muds has an interesting effect. As the sand spreads out across the sea floor, it presses into the soft muds. The results are the crenulated surfaces we described earlier. They are called sole marks. There are a number of different types of sole marks and, technically, these ones are called “squamiform load casts.” Let’s not get too concerned with the exact terminology and instead try to appreciate the aesthetics of these structures.

They are rather remarkable in the details of their sculpturing and we have trouble finding just the right adjectives for them. Take a look at our illustration and you will get a good impression of them. These soles are common throughout the Austin Glen Formation and, once you have an eye for them, you may be able to find others. We origins: underwater avalanches, triggered by great earthquakes; it’s quite a scenario and very typical of what we find when we know what to look for in the rocks.

================================================================

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”