The Glaciers of Hunter Mountain April 25, 2018

HUNTER MOUNTAIN BESIEGED . . . AGAIN

On The Rocks

August 29, 1996 1996

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

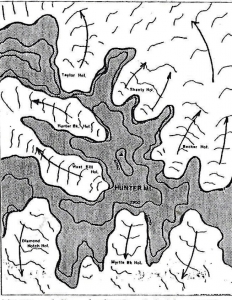

They say that it is human nature that the end of one conflict often bears the seeds of the next. This somber observation may be the case with Hunter Mountain, the second highest mountain of the Catskills. Recently (That was in1996) there was a proposal to alter the New York State constitution in order to allow the development of about 3,000 acres at the summit of Hunter Mountain. This would have allowed the expansion of the Hunter ski complex into something comparable to what we now see in Vermont. Currently skiing on Hunter is confined to the “Colonels Chair” which lies on the slopes of Shanty Hollow. If the proposal had gone through (It didn’t), skiing would have been expanded to Taylor Hollow to the northeast and Becker Hollow to the east. These three hollows have origins that date back to the last time the mountain was besieged. That was during the ice age when the proposed ski bowls of Hunter were occupied, not by skiers, but by Alpine glaciers.

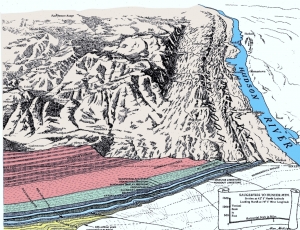

Few people realize the role that glaciers played in making our Catskill landscapes. The story takes us back to a chapter in glacial history described as the Wisconsin glaciation. Catskill glacial history is complex, but there were two very different phases. First there was a time when a great, half mile thick sheet of ice swept across our mountains. The Catskills then resembled the high ice plains of today’s Antarctica. By 16,000 years ago, however, the Catskills had escaped the worst grip of this phase. The great thick ice sheet was gone, but all was not over yet. Glaciers were still found in the shaded valleys, and also in the high mountain niches that were giving birth to a number of Alpine glaciers. If you are familiar with the images of the Swiss Alps of today then you know that high up in the Alps, large glaciers form in pre-existing hollows. These are nourished by snowfall and, with cold conditions, these picturesque Alpine glaciers descend the slopes and flow into the valleys below. That was the case with Hunter Mountain.

As time went by these glaciers modified their own Alpine niches. Glacial ice forms a sticky bond with the rock beneath it, and as the ice moves, it plucks loose large amounts of this rock. Alpine ice is thus a very effective agent of erosion. Given enough time, this expanded the niches and enlarged them into beautiful, bowl-shaped features called “cirques.”

There are a lot of cirques in the Catskills, but few of them are as well developed as those of the Alps. This phase of glaciation was too short for Swiss-like landscape to develop. Warmer conditions returned, and the Alpine glaciers melted. Nevertheless Hunter Mountain displays some of the best cirque landscape seen in the Catskills. In addition to the three hollows we mentioned earlier, there are the hollows at Myrtle Brook, Diamond Notch, West Kill and Hunter Brook. All seem to have once harbored glaciers. Some of these can be seen from Rte. 23A, below.

Cirques, left and right of the ski slopes.

A map of Hunter Mt. showing its seven Alpine glaciers.

The effects of glaciation persist long after the ice is gone. These bowls initiate what we call “watersheds.” The hollows are ideally suited for the purposes of gathering rainwater and passing it on to the river systems below. Of the seven hollows which surround Hunter Mountain, five of them feed water into the Schoharie Creek watershed. Only one of these five, Shanty Hollow, is currently a ski slope, but Taylor and Becker Hollows were planned to be added. Watershed protection was one of the most important reasons why the State purchased the land in the first place, and was one of the primary reasons for opposition to the ski slope expansion.

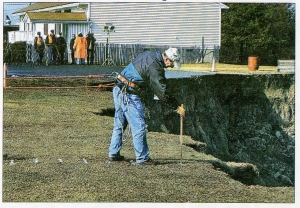

You can see some of this Alpine landscape. From West Kill Valley take the Devil’s Path up the western slope of Hunter Mountain. There is a fine ledge at the top of the trail. That is the top of a cirque. The cliff below drops off into an Alpine glacier’s niche. Look west into the valley of West Kill. The beautiful U-shaped valley you see is the product of the glacier’s erosion as it flowed down the valley.

View of U-shaped West Kill Valley

Contact the author’s at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.”