March of the glaciers

Stories in Stone

The Columbia County Independent

Jan. 2006

Robert and Johanna Titus

We would like to do another column on the topic of drumlins. These are little ice age hills which were sculpted by the advancing glaciers of about 14,000 years ago. Theories vary considerably but most geologists argue that ice sculpted coarse sediments into the shape of an upside down spoon bowl. They are striking features when viewed from the ground or air; once you have learned to recognize them, you will be surprised at how many there are. We have long marveled at how many drumlins there are in the Mohawk and Hudson Valleys. New York State is renowned for this. The fact is that the lion’s share of the world’s drumlins is found in our state. Makes you swell with regional pride, doesn’t it? Well, it should.

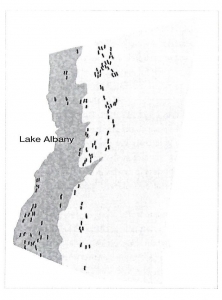

Map of Columbia County showing locations of drumlins. Hudson River on left.

Seeing them from the ground is something that we will explore again, sometime in the future, but today we want to work from a graphic. It’s from our book “The Hudson Valley in the Ice Age. It’s adapted from the New York Geological Survey topographic maps of our region, and it shows just how important drumlins are in our region. We can learn to appreciate what they represent, and the history they speak to us of.

Picture of a drumlin.

Our map shows a host of drumlins. Each oval represents a single occurrence and we count 120 or so of them; there are probably more. Each oval is parallel with long axis its drumlin and that records the direction of the glacier’s flow. Collectively they record the passage of a glacier that, though big, wasn’t as large as some earlier ones. It was just small enough to be channeled by the valley. You can “see” its flow from the drumlins. Most of the motion is due south, but some of the ice veered to the southeast. Everything is near the bottom of the Hudson Valley. Let’s call it the Hudson Valley glacier.

Though big, we are uncertain of its full extent. The many drumlins we see on the map cover all of Glacial Lake Albany and stretch a little beyond it to the east. Evidently, the ice had little difficulty moving across the old lake bottom. The landscape here was smooth and flat and offered little to block the flow. To the east the landscape is a little more elevated, and the ice only pressed a short distance that way. Thus the ice was essentially confined to the Hudson Valley. The glacier evidently thinned to the south. Around Kinderhook, drumlins reach elevations up to 650 feet. That drops to between 200 and 300 around Clermont.

You can understand why geologists get excited about this sort of thing. With maps like these we can closely document the last stages in the great glaciation that brought the ice age to an end in our region. Our drumlins bring the ice to life and graphically speak to us of what the glaciers were doing.

And our story has a lot of detail to it. The ice had previously retreated to somewhere in the north. This had left behind Glacial Lake Albany which filled most of the Hudson Valley. But the drumlins are features that lie on top of the lake beds; they must be younger. That means there had been one last readvance. When, exactly, this happened we cannot say with precision. The advance came after the time of the lake, but how many years later we do not know, probably not many.

We are forced to depend on our imaginations a little here, at least until better evidence turns up. It is quite possible that the lake was still there as the ice advanced. It would be easy for the ice to “skate” across the frozen lake. That would account for its apparent confinement to the lake area. Other geologists date it to a bit earlier than that glacial advance.

Remember the last time you skated upon a large pond, or better, on a large lake. Now, in your mind’s eye, look north and watch as a glacier is moving slowly toward you. It’s quite a vision and it may well have happened right around here.

Reach the authors at randjtitus@prodigy,net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.

Increasing evidence for catastrophic flood outwash as the cause of drumlins can be found in the May 1989 issue of Sedimentary Geology. Catastrophic outflow flooding is now known to have swept across most of New York. A good example is the Hudson River flowing through the Hudson highlands. How does a river flow uphill through and over mountains? It does not. It began by covering a depth higher than those mountains and upon draining low enough, it then poured over a low spot in the crest of those mountains, and then like Niagara Falls, it cut a gorge through those mountains lower and lower until you have the water level course today right through those mountains. This is known as a water gap, and the Delaware Water Gap is another prominent example.