CATSKILL PREHISTORIC MONSTERS:

APPARITIONS OF THE ANCIENT SEA SCORPIONS

The Catskill Geologist

Winter l993

Updated by Robert and Johanna Titus

One of our favorite authors is H. P. Lovecraft. He was a horror and fantasy writer, featured mostly in long-ago pulpy magazines such as Weird Tales. Lovecraft’s work, while well thought of, is hardly great literature; it does, however, make very fine reading. His stories were usually set in isolated, backwater New England villages of the l920’s. Villainous creatures and people possessed by evil spirits were commonplace in his plots, as were monsters, aliens, ghosts and other terrible apparitions. Very often you never really did figure out exactly what kind of entity haunted these Lovecraft stories. Typically, his tales had a “lost in time” feeling to them; hence their appeal to a geologist. Often these awful Lovecraft characters were from very ancient epochs in Earth history. Much of the intrigue was in the fact that these dark entities had long ago possessed great mystical powers. Later they lost control of these powers and then they, themselves, fell into the possession of those very same evils. Their defeat banished them to a kind of timelessness. They were only able to take out their terrible rage on those weak mortals who fell within their grasp. Fantastic as Lovecraft’s stories were, there was a kind of eerie plausibility to them. The stories worked because communications were so much poorer back then and so much of our nation’s rural landscape was isolated and mysterious. After all, back then who knew exactly what all lay out there lurking in the woods? Similarly, do we really know all that is hidden out there in the woods of today’s Catskills?

Lovecraft rarely featured the Catskills in his stories, and we wonder how often he visited our mountains. It’s too bad, as our dark cloves and isolated valleys would have made perfect settings for his stories – malignant versions of “Rip Van Winkle!” But science often provides us with real-life stories, nearly as good as anything Lovecraft could have written. And, here in the Catskills, some of these stories abound with monsters – great, creepy, crawling ones at that. The season is cold, dark and gloomy right now, so set a fire in the fireplace and turn down the lights. We would like to tell you about a real-life, monster-ridden town, right here in the Catskills. This is a town where Lovecraftesque monsters really are lurking in the dark; they’re hiding in the fetid, moldy, and darkened foliage of the Catskills. Our rock-Gothic tale even involves the long-ago discovery of the dead and dismembered head and limbs of an ancient monster. And this necromantic tale reminds us that we share this landscape with a heritage of antediluvian beasts that went before us. And maybe, just maybe, you can come face to face with one of these creatures. We’re not kidding! They’re out there, if you’re “lucky” enough to encounter one.

First you’re probably wondering what peaceful Catskill village harbors the ghostly apparitions of those monsters of the past. Let’s end the suspense: the answer is Andes. If you haven’t visited Andes before, it’s a pretty little hamlet on Rte. 28 in the western Catskills. Small and isolated, with plenty of l9th Century buildings and homes, it would have been a perfect setting for a Lovecraft story in the 1920’s. Today it remains a remarkably well-preserved old town and is very much worth a visit. Look especially for some nicely kept old homes and the old bank building which is now a real estate office.

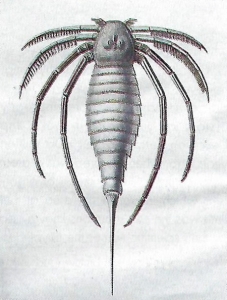

Our story is not about sightseeing, however; it’s about monsters. In recent articles we have described the early history of our Catskill rocks, the Devonian Period, about 380 million years ago, when this area was a great delta complex. One group of organisms, which inhabited the area at that time, was the sea scorpions known also by their scientific name, the eurypterids. We have several pictures to show you. Take a look at the first (fig. l). It is a painting by the famous paleontological artist, Charles Knight. Knight made his

reputation as an artist primarily by painting dinosaurs, but he also did a number of ancient sea

scapes to illustrate invertebrate fossil species. This Knight painting shows several eurypterids inhabiting a very hypothetical Devonian seafloor. The two largest forms in the scene are of the types that have been found in the Catskills. The one on the left is known as Pterygotus; the one on the right was called Stylonurus until its name was changed to Hallipterus. Pterygotus has been found in the upper reaches of Schoharie Creek near Gilboa. We will write about that one some other time. Hallipteus, found in Andes, is the one that we want to talk about today.

Eurypterids, now entirely extinct, were still fairly common in the Devonian Period. They crawled and swam in the nearshore marine waters, the brackish coastal estuaries, and even in the nearshore freshwater rivers. If you have read our earlier articles, you will already know that these environments are commonly represented in Catskill rocks. You will be reminded of scorpions when you examine these pictures, and there is a good reason for that. The scorpions and eurypterids are closely related. In fact, today’s living scorpions probably list the eurypterids in their family tree. Hence the common name, sea scorpion.

Eurypterids were probably quite common in the Devonian Catskill area, but they are rare as fossils. Their skeletons were sturdy in life, but were composed of materials which usually decayed after death. We simply do not see many of them as fossils. Take a look at our second picture (fig. 2). This specimen is the carapace (head) of Hallipterus

excelsior, one of the largest eurypterids ever found. This head, alone, is ten inches long. It was found during the very early l880’s by an Andes farmer in a little quarry. The quarry was close to the town library and the World War I monument, but it seems to be overgrown and buried now; we looked for it recently but could not find it. The specimen was found on a loose boulder, not part of any bedrock. It probably came down the Tremperskill valley from the hills above. The rest of the body, if it still exists, has never been located. The fossil was acquired by M. Linn Bruce, who was then a student at Rutgers College. Bruce, who would later become lieutenant-governor of New York, donated the specimen to Rutgers. One of us (Robert) was an undergraduate at Rutgers and can very well remember that specimen upstairs in the Museum of Geology Hall. Perhaps it’s still there. If so, you can see it if you are ever in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

Only a few other fragmental specimens of this type have ever been found. The next picture (fig. 3) shows one of them; these are appendage fragments of a very closely

related species from Pennsylvania. When these fossils were discovered, nobody knew what the whole animal looked like, or even how big it was. Later a paleontologist named Charles Beecher found related species from England and was able to produce the reconstruction we show you in figure four. If his reconstruction is accurate (and it may not be), then this was quite a monster. At an estimated 54 inches in length, this was a lot bigger than your average land scorpion, not something you would worry about finding in your boots.

If you already are a fossil hunter, you would probably like to add one of these to your collection. But, alas, the chances are slim. In fact we don’t expect any of you are likely to find one, but we would like you to know what they look like, just in case. Eurypterids are really scarce in the Catskills; we know of only the two which were found in Andes and Gilboa. But there may be more, and if you feel like doing a little monster hunting in the Catskills, we would certainly encourage you to try. Pay no attention to the red sandstones of the Catskills; they’re old soils and don’t contain marine fossils. Instead, watch the brown and olive gray strata which are probably river beds. Don’t expect to find a complete eurypterid; fossils that good just do not show up. Instead watch for eurypterid parts. Study figure four, so you will know what to look for, and … good luck! (If you do find one, please let us know.)

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net.