The Earthquake at Mexico City

The Catskill Geologists; The Mountain Eagle; Sept 19, 2017

Robert and Johanna Titus

For the second time in a thirty years, Mexico City has experienced an awful earthquake. It was actually about 75 miles southeast of the city; that’s close enough. This one measured about a 7.1 on the famous Richter scale. That’s a powerful earthquake. Early reports claim that 40 buildings came down and several hundred people died. We don’t have many earthquakes in our region, and when they do occur they don’t amount to much. Still, we can’t help saying something about it; it has been a big geological event.

Why was it so bad? Well, as we understand it, Mexico City lies within a series of very sizable geological faults. And they are circular faults; the crust has broken up into a series of concentric circles. These are also active faults; they generate earthquakes from time to time. That’s bad enough, but it gets worse. The basin that lies inside these faults has filled with lake sediments. These tend to be wet, and that makes them very unstable during any earthquakes. The seismic waves pass through the sediments and they become liquefied. Mexico City finds itself shaking on a liquefied landscape.

That accounts for a lot of the damage.

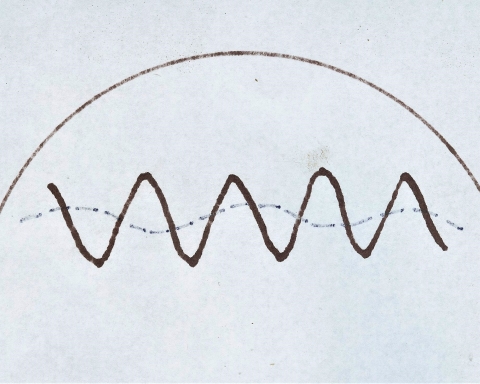

We have found a way to demonstrate this. We like to get a thick pint glass out and fill it to the very top with water (beer when Robert is pouring). When the fluid is at the absolute top, we are ready to go on with our “experiment.” We pound a fist right next to the glass and watch the water at the surface. Most of the time we see waves radiating inward from the outer edge of the glass. Something very much like that happens to the Mexico City basin. Perform this experiment in your own home and then imagine the results scaled up to the size of a great city. Now, you understand what happened the past week.

The news is not all bad. These awful events present architects and engineers with wonderful opportunities to learn how to design earthquake resistant buildings.

That’s what happened in 1985, after the last big earthquake in the city. In the months and years that followed, experts studied the buildings that had come down along with those that survived. What, they asked, were the differences? How could new buildings be constructed so as to minimize the threats.

We will give you one example. Mexico City architects found that L-shaped buildings were very likely to collapse during a quake. One side of the L vibrated in one direction; the other half vibrated differently. The competing stresses brought those buildings down. They looked good but they were dangerous. Well, when these buildings were replaced, architects knew better than to use L-shapes.

The long and the short of it is that the rebuilding of Mexico City benefitted from the 1985 experience. Now all those earthquake resistant building have been tested by a new quake. We expect that at this very minute engineers are toting up the scores. Which buildings “won” and which buildings “lost.” Which of the new designs had succeeded and which didn’t?

This is progress, but it is a very expensive way to learn.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The

Catskill Geologist.” Read their blog at “thecatskillgeologist.com.”