The Devonian at Pratt’s Rock

The Catskill Geologists; The Mountain Eagle, June 28, 2019

Robert and Johanna Titus

We have been doing a series of columns about Pratt’s Rock, which is, of course, in Prattsville. The stone carvings up there have, for 150 years or so, been attracting visitors. Today Pratt’s Rock is showing its age; it needs more than a cleaning; it needs a full refurbishing and that is what is being planned. Renowned landscape architect, Michael Van Valkenburgh, has been recruited to play a leading role. We have been wanting to contribute to all this by describing the geological heritage of the site. We think that’s an important aspect of the history of Pratt’s Rock and Prattsville itself. In our last two columns, we have described the ice age history there. That was only about 15,000 years ago. But today, we go back almost 380 million years to visit what geologists call the Devonian time period. All of the stratified rocks at Pratt Rock are as they were when first deposited during the Devonian Period.

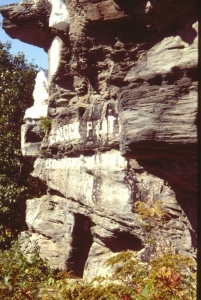

Actually, we will start off by visiting what was intended to be Colonel Zadock Pratt’s crypt and then, from there, we will travel into that Devonian past. Take a look at our photo. You will see the Pratt chamber opening on the lower left. Our understanding of the story is that Colonel Pratt would have been interred there except that it started leaking. Just above that chamber, are some curious strata. Do you see how they are inclined to the right? We think that most local geologists would recognize this as being the left shore of a Devonian river. It needs a name and we love to name things; let’s call it the Pratt River.

April 3, 379,998,163 BC – We are the mind’s eyes, and we have gone back those almost 380 million years and we are hovering above what will someday be Prattsville. We slowly turn a full 360 degrees and survey the landscapes below. We are just a few hundred feet above what has been called the Catskill Delta. Off to the east, a hundred miles or so, rises an enormous mountain range. These are the Acadian Mountains. They tower above what are the Berkshire Mountains today.

The Catskill Delta lies spread out before and below the Acadians It passes beneath us and continues perhaps another hundred miles to the west. Out that way is a broad shallow ocean, called the Catskill Sea. We turn another 360 degrees and appreciate how flat it all is. As far as we can see, there are rivers, an endless number of them. This is not surprising; large deltas always display large numbers of rivers. They are called distributaries and they always fan out across a delta. These rivers eventually “distributed” their waters into the distant Catskill Sea,

We, the minds eyes, drift downwards and we approach the nearest of these distributaries; it’s the Pratt River. We hang in the air, just a few feet above its waters. We look upstream and downstream. On this day there is only a lazy current slowly passing by. It is high noon on a sunny day, and we can see to the bottom. Down below are what we think are fish. But they are clumsy looking animals, thickly armored with heavy bones. Fish have only recently evolved into such river ecologies and they are not yet very good at it.

Below the fish, on the stream bottom, are scores of three-inch long clams. They sit there, all of them facing upstream. They face into the river currents and are able to sift out bits of biologic matter. This is, for them, food. Similar clams still live in Catskill lakes.

The riverbanks are densely populated with trees. But they are all so primitive looking. Long straight trunks rise up about 20 feet. There are no branches, but a strange foliage crowns each tree. It’s hard to find the right words to describe these crowns. There are no flowers, no seeds, no nuts; there are not even proper leaves. There are “appendages” that are green and photosynthetic; there are others that are reproductive. Those have black spore-producing bodies dangling from them. We look again, far and wide; there are no broad-leafed trees; neither are there any evergreens. This is a primitive forest, populated by primitive trees.

On the forest floor are some relatively familiar creatures We see millipedes, centipedes and spiders. Then we spot silverfish. These six-legged invertebrates are among the world’s most primitive insects. But there are no mammals, none at all. Neither are there any reptiles or even amphibians. There are no birds high above, singing in any of these “trees.” It is a quiet day and there are no sounds whatsoever. The silence is unnerving.

All this is the famed Gilboa Forest. It is evolution’s first-ever attempt at forest ecology, and it once grew and thrived right where Pratt’s Rock is today. Our journey through time has been a journey through the history of life itself.

Contact the authors at randjtitus@prodigy.net. Join their facebook page “The Catskill Geologist.” Read their blogs at “thecatskillgeologist.com.” But mostly, go and visit Pratt’s Rock sometime this summer.